The G-20 Economies and Protectionism

The G-20 should rein in the most important trade distortions, many of which don’t receive the attention they deserve in official monitoring of protectionism.

Trade data comes out with lag—even so, the latest readings are worrying. In late May the OECD confirmed sharp falls in Q1 2015 exports from the G-7 nations and from several large emerging nations (the OECD includes here Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, and South Africa.) On 24 June 2015 the respected CPB World Trade Monitor confirmed falls in both the volume and the average price of world trade. Falling prices are not confined to volatile commodities markets—average prices of imported manufactures have now fallen back to levels last seen in May 2009.

Worse, when measured in US dollars, total exports of the G-7 countries have yet to recover to pre-crisis peaks. Among the large emerging markets mentioned above, only China manages to export more than before the crisis. All of this diminishes the contribution that exports are making to the recoveries of G-20 economies. The markdowns in forecasted growth for 2015 and 2016 reported in the IMF’s July 2015 World Economic Outlook suggest that G-20 economies cannot afford another pronounced export slowdown.

All too often fast export growth is used to demote trade policy; with the current global economic slowdown there is no room for complacency.

Official reports on protectionism substantially understates threats to export recovery

No doubt demand factors – amplified in some cases by supply chains – have had a part to play in the global export slowdown. However, from the beginning of the crisis, the G-20 has rightly been concerned about protectionism and preventing repetition of the mistakes of the 1930s, when official monitoring of protectionism began.

Coloured perhaps by references to the 1930s, WTO reports on protectionism have focused primarily on trade restrictions. The latest WTO report, published on 12 June 2015, emphasised a slight deceleration in the monthly resort to trade restrictions by G-20 countries. Subsequently, on 7 July 2015, the independent Global Trade Alert (GTA) published its report on crisis-era trade distortions. Covering the same policies and monitoring the same countries as the WTO; the GTA team found:

- 156 trade restrictive measures have been imposed by the G-20 from mid-October 2014 to mid-May 2015, 31% more than the WTO.

- 2080 trade restrictive measures have been imposed by the G-20 since 1 November 2008, 53% more than the WTO.

- Official monitoring consistently understates the resort to trade distortions by the G-20. The G-20 work program on trade should be informed by the most up-to-date and comprehensive statistics on resort to trade distortions.

The biggest distortion to world trade comes from artificial export incentives, not import restrictions

New evidence on the relative importance of different types of trade distortion is now available. Over 6,800 state measures taken by governments worldwide since the first G-20 Leaders Summit have been documented by the independent Global Trade Alert team and, where the data is available, conservative estimates of the share of G-20 exports potentially affected by each trade distortion were computed. Figures 1 and 2 show the main findings.

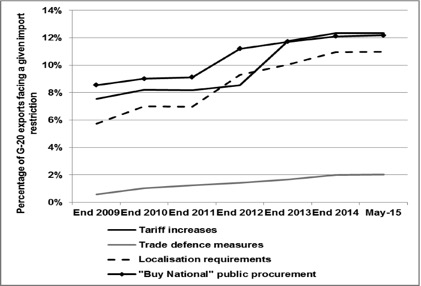

The WTO’s reported estimates of G-20 trade affected by import restrictions are generally very small and this is because it focuses principally on recording anti-dumping, anti-subsidy, and safeguard actions. Figure 1 confirms that the share of G-20 exports confronting trade barriers arising from this narrow set of policies has been less than 2% during the crisis era.

An almost exclusive focus on trade defence is misleading for two reasons.

First, other import restrictions have been growing in importance over time. The percentage of G-20 exports facing new tariff increases has risen from 7.5% at the end of 2009 to over 12% by May 2015. A growing percentage of G-20 exports are in products where new “Buy National” provisions have been imposed on state spending. In terms of exports at risk, the fastest growth among import restrictions are in new measures that require local content to be purchased—a finding which accords with the growing attention so-called “localisation” measures are receiving in trade policy circles.

Figure 1: The share of G-20 exports affected by import restrictions—in particular, by non-tariff barriers—is rising.

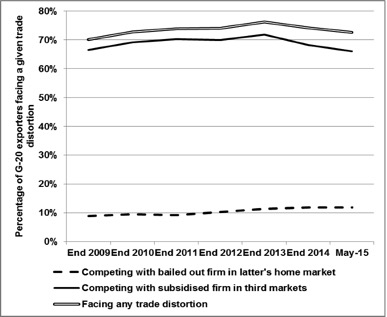

Second, for all the attention given to import restrictions it is the spread of incentives to export (normally hidden in arcane provisions in national tax systems) where the action really is. Such has been the spread of export incentives since the crisis began that around 70% of G- 20 exports compete against at least one subsidised foreign rival in third markets (see Figure 2). The scale of the export incentives available, in particular in manufacturing, may help explain why export prices of these goods aren’t growing. Subsidised firms can reduce their prices in a bid to win contracts and other firms must match those price cuts. Finance ministries ought to be worried about the total cost of export-related tax breaks as well.

Figure 2: The exposure of G-20 exports to import restrictions, however, pales in comparison to the scale of subsidised rivals competing for market share in third markets.

Overall, as Figure 2 shows, since the crisis began 75% of G-20 exports face at least one new trade distortion. That percentage hasn’t fallen. This finding must call into question any confident assertions that governments around the world have refrained from introducing trade distortions since the crisis began or that protectionism shot up in 2009 and has been removed. Moreover, the fact that so many of the contemporary trade distortions are not traditional tariff increases and the like points to the wisdom of last year’s request by the G-20 for analysis of non-tariff measures. The broader lesson for policymakers is:

Not repeating the mistakes of the 1930s means more than not hiking tariffs and imposing import quotas. Focusing on one type of trade distortion encourages some to use others.

Recommendations for the G-20

To contribute to the revival of global exports, and recognising the role that non-transparent policies play in deterring firms from selling in world markets because they face greater uncertainty, the G-20 should:

- Highlight the global trade slowdown as a major concern and a threat to growth.

- Reaffirm the protectionist pledge.

- Mandate the WTO in its monitoring of trade policies to give as much attention to policies that artificially stimulate exports as it does to import and export restrictions.

- Mandate the WTO to update its earlier reported totals for protectionism to take account of information subsequently received about policies implemented by the G-20.

Prepared by Professor Simon J. Evenett and Dr. Johannes Fritz of the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland. Professor Evenett is co-Director of the most established group of international trade researchers in Europe and Coordinator of the Global Trade Alert, an independent watchdog on trade policy. This is an extract from the original report “The G-20 and Protectionism—A July 2015 Update” which can be found here.