Reining in the "Unruly Horse" of Jus Cogens

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties opened for signature fifty years ago this week, on 23 May 1969. During the negotiations, the issue that most divided the West and the newly independent states concerned jus cogens, the idea of overriding norms in international law. Could colonialism be considered alongside aggression and genocide as grounds for the invalidation of treaties?

The idea of a “treaty on treaties” was agreed upon by the International Law Commission (ILC) in 1961, after two UN conferences on the law of the sea had failed to decide the crucial question of the breadth of the territorial sea. The collapse of the second of these conferences in 1960, assisted by some Asian and Latin American states, triggered a crisis of confidence in the Western camp about multilateral treaty-making generally. No matter how much energy the West expended on securing their objectives — cajoling, berating, threatening — they could not compel enough states to vote for their positions. They therefore attempted instead to draw the newly independent states into the creation of a regime governing treaties with the aim, as British legal advisor Ian Sinclair put it, of “permit[ting] them to participate in the elaboration of the principles by which they would be bound.”

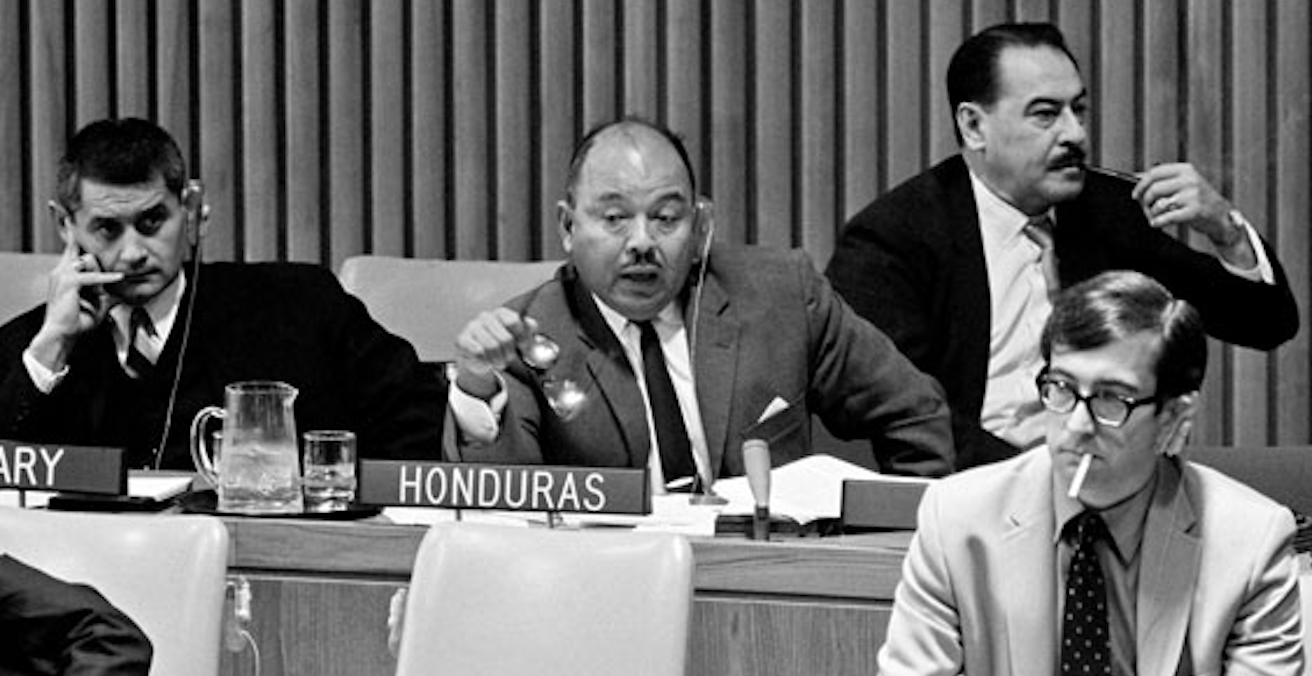

At the Vienna conference on the law of treaties in 1968 and 1969, the tensions between the Western powers and the newly independent states were on full display. Many African and Asian nations aimed to create the means to disentangle themselves from disadvantageous treaties imposed on them by the colonial powers. The Western states, by contrast, emphasised upholding the principle of pacta sunt servanda — agreements must be kept. The question, then, was where to strike the balance between the stability of treaties and the progressive development of international law.

Things came to a head over Part V of the ILC draft, which set out the circumstances under which a state might legitimately extract itself from its treaty obligations. This stated that a treaty could be invalidated if it had been procured as a result of error, fraud, corruption or coercion, or conflicted with a peremptory norm of general international law. The last generated the most heat at the conference. Could unequal treaties, or indeed colonialism itself, be deemed to violate peremptory norms — jus cogens, or norms from which no derogation is permitted? The British suggested that it might:

“Since there is no agreement on what are peremptory norms, we might soon find that the existence of a colony was contrary to the peremptory norm contained in [the anti-colonial General Assembly] Resolution 1514. A state on discovering that it had made a bad bargain might argue that its sovereign equality was infringed.”

The Australians, mindful of Papua and New Guinea, were thinking along similar lines. Ralph Harry, Australian delegation leader at the 1968 conference session, noted that the Asian and African non-aligned states — led by India, Ghana, and Kenya — embraced the jus cogens doctrine with “almost religious fervour,” and suggested that their concerns covered not only unequal treaties inherited by post-colonial states, but also issues such as apartheid, the 1966 South West Africa case and racial discrimination. Beyond the peremptory norms commonly identified at the time — such as aggression, slavery, piracy and genocide — there was the prospect of others emerging, such as the rights articulated in the recently signed human rights covenants.

The Western powers could not openly oppose the idea of peremptory norms — after all, the US, UK and France had themselves invoked them against the former German and Japanese leaders at the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals. They therefore acknowledged the doctrine in principle while arguing that it was not yet ripe for codification. Their attempts to rein in the ‘unruly horse’ of jus cogens — as one Australian report put it — occupied considerable time and energy. Initially they tried to delete draft articles 50 and 61 on existing and emerging peremptory norms. In the process, Harry delivered a speech in which he criticised the first for failing to specify what the norms were, which made the concept as elusive as “flying saucers” or “a will-o-the-wisp.” This sort of argument did not go down well. The draft prompted a “steamy three-way debate terminating in extreme bad temper at midnight” at which point — the New Zealand delegate Tony Small reported — “the majority of the committee of the whole lost patience with all this, and the Afro Asian streamroller was applied to try and compel showdown voting on the article.”

Thwarted in their attempts to delete the offending jus cogens articles, the Western powers then tried to impose restrictions. First, they tried to ensure that the doctrine could not morph into new forms. As a result, on Western insistence, article 53 of the convention — the renumbered draft article 50 — stated that a peremptory norm was only such if it had been “accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole.” Second, they made accepting the jus cogens articles conditional on all parties’ accepting compulsory third-party settlement of disputes over the issue, either before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or through arbitration. Without this safeguard, they thought states would “irresponsibly and without restraint” unilaterally declare treaties to be invalid on the grounds that they had violated a peremptory norm.

The newly independent states, Harry noted, challenged the idea of compulsory settlement, arguing that “treaties contrary to jus cogens, or secured by coercion, are absolutely void ab initio”, and refusing to admit that “the existence of voidness requires to be established by third party procedures.” A major factor in their reluctance to accept third-party rulings was their suspicion that the ICJ was less than impartial after its controversial judgment on the 1966 South West Africa case. This, decided by the Australian president Percy Spender’s casting vote, denied Ethiopia and Liberia’s claim that South Africa had breached its mandate duties in South West Africa.

Despite opposition by African and Asian states, the Western powers nevertheless insisted on compulsory settlement for jus cogens issues. If states were unable to resolve a dispute over the application or interpretation of the treaty within twelve months, convention article 66(a) specified that jus cogens issues must be submitted to the ICJ “unless the parties by common consent agree to submit the dispute to arbitration” — while article 66(b) and the annex also specified that other parts of Part V must be submitted to conciliation.

This compulsory approach was new. Some previous treaty regimes provided optional protocols, whereby states could opt into compulsory mechanisms, but not many states ratified them. Introducing compulsory settlement applicable to all parties to the Vienna convention broke a deadlock: the non-aligned states got their jus cogens articles, and the West acquired the means to contest a unilateral claim that a treaty was invalid on jus cogens grounds.

The result? Most parties eventually ratified or acceded to the treaty, including Australia, which, despite objecting to the original jus cogens articles, acceded to it in 1974 without reservation.

Dr Kirsten Sellars is Visiting Fellow, Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, Australian National University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.