Bali Nine: Hypocrisy, Politics and Courts Play Out in Death Row Lottery

One of the strongest arguments against the death penalty is that its administration is fundamentally unfair.

Too often, the question of who receives a death sentence and whether and when it is actually carried out becomes more a matter of politics than of facts and law. This is certainly the case for the two Australians, Myuran Sukumaran and Andrew Chan, on death row in Indonesia. They find themselves at the centre of a series of complex political controversies, all of which could directly affect their chances of survival.

Sukumaran and Chan are the only members of the Bali Nine still sentenced to death for their role in attempting to smuggle 8.3 kilograms of heroin out of Bali to Australia in 2005. Indonesian President Joko Widodo has now rejected both Sukumaran’s and Chan’s pleas for clemency, leaving the pair facing execution by firing squad.

Clemency is last hope on death row

An application for clemency is usually made when the judicial process is exhausted. It is intended to be the last chance for a lighter sentence before execution takes place. The Chief Prosecutor’s office has indicated they usually execute co-offenders together.

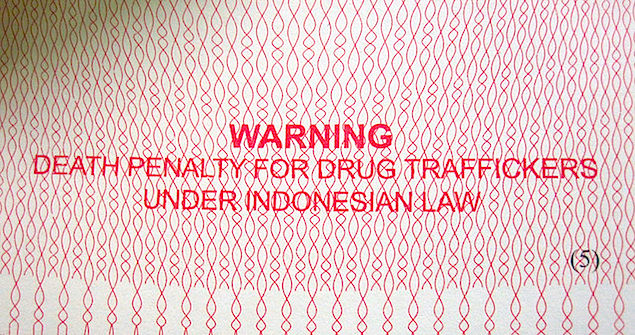

Jokowi’s decisions on Chan and Sukumaran are consistent with recent statements he has made that he would not grant clemency to drug offenders. The death penalty is available in Indonesia for 17 offences but usually only imposed for drugs, terrorism and murder.

For decades the majority of executions in South-East Asia have been for drugs offences. Now Indonesian officials have said they aim to build a reputation for harsh treatment of drug offenders to match neighbouring Singapore and Malaysia, where, unlike Indonesia, death is mandatory in many drugs cases.

Jokowi’s refusal to grant clemency also reflects a decision made in 2013 by his predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, to end the informal moratorium on executions he put in place after the Bali bombers (Imam Samudra, Mukhlas and Amrozi) were executed in November 2008. In 2013, executions resumed, targets were set and four prisoners met their deaths. Last weekend, six more were executed, including five foreigners.

A double standard for Indonesians abroad

Indonesia’s efforts to prevent its own citizens being executed overseas therefore seem odd indeed. In recent years it established a taskforce and spent millions of dollars to hire lawyers and, where permitted, pay “blood money” to ensure that Indonesian domestic workers in countries including Saudi Arabia and Malaysia escape the death penalty.

This obvious double standard has drawn much criticism, including from Indonesian civil society. The government justifies it by drawing a clear distinction between, on one hand, its overseas workers – many of them maids who have murdered abusive employers – and, on other other hand, drug offenders, whom it categorises with terrorists as “mass murderers”. This distinction has support in Indonesia, where a high-profile “war on drugs” policy has been in place for years and many locals rely on overseas workers for remittances.

However, it does make it much harder for Indonesia to run an in-principle argument in favour of the death penalty, as leading Indonesian human rights organisations such as NGOs KontraS (Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence) and LBH (the Legal Aid Institute) have been arguing.

Many Indonesians still support the death penalty, including some active anti-drug NGOs. There is, however, a growing debate about whether it is still appropriate in an open liberal democratic state committed to human rights of the kind Indonesia claims to have become since Soeharto fell in 1998.

A question of politics as much as law

This ambivalence over how the death penalty sits with recognition of human rights is reflected in the “bob each way” decision the Indonesian Constitutional Court made in 2007. It held that execution is not inconsistent with the guarantee of right to life in its liberal post-Soeharto constitution.

However, the court also recommended that prisoners who have been on death row for ten years and have shown reform and rehabilitation should have their sentences commuted to imprisonment.

Jimly Asshiddiqie, the Constitutional Court Chief Justice at the time, has recently complained that the government has completely ignored this part of the judgment. He has also indicated discomfort with his court’s decision to uphold the death penalty, suggesting the time may be right to abolish it.

Sukumaran and Chan were arrested in 2005, and prison authorities have described them as reformed model prisoners. If the Constitutional Court’s proposal was implemented they would have a strong argument for their death sentences being replaced by long jail terms.

As this suggests, Indonesia may be undergoing a slow transition towards abolition. Many newspapers, including the leading daily, Kompas, have published articles criticising Jokowi’s decision to resume executions. But this shift in public opinion does not seem to big enough or moving fast enough to save Sukumaran and Chan.

It may not move Jokowi much either. Indonesian political observers say that while he is a strong democrat and anti-corruption reformer, he is personally morally conservative and not greatly focused on human rights issues.

They also say that Jokowi is under massive political pressure to match the decisive hardline “tough guy” image of his defeated presidential rival, former general Prabowo Subianto, who made much of “standing up” to foreign influences.

Jokowi lacks strong elite support and is fighting hard to build a workable coalition to overcome Prabowo’s stranglehold on the national legislature, which has so far prevented any laws being passed. While granting mercy to Sukumaran and Chan might have helped Jokowi with the second-rank challenge of building a relationship with Australia, he might well have seen it as too damaging for his own political survival.

Courts divided over appeal rights

Sukumaran and Chan’s lawyers have announced they will soon lodge a second application with the Supreme Court to re-open their case. This is known as a “PK” or “Reconsideration”.

As might be expected, lawyers for the pair will argue that Sukumaran and Chan’s rehabilitation should be taken into account. Indonesian authorities have said they will probably not execute while a related court case is pending, but the PK faces two problems. Both relate to political tensions between the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court, Indonesia’s judicial “twin peaks”.

The Constitutional Court says there is no limit on the number of PKs a person may bring. The Supreme Court says only one is possible. The Supreme Court seems not to consider itself bound by the Constitutional Court, and may therefore reject Sukumaran and Chan’s second PK out of hand.

For the same reason, if the Supreme Court does consider the PK on its merits, it may pay little heed to the Constitutional Court’s suggestion that after ten years’ rehabilitation, death penalty sentences should be commuted. Discussions have been arranged between the two courts to resolve their differences, but so far without much success.

This all means that despite the huge effort being made by their Indonesian and Australian lawyers – and by the Australian government – Sukumaran and Chan’s future hangs on matters that have little to do with the actual crimes they committed or their own conduct since then.

Whether Sukumaran and Chan are executed depends on how all these factors play out and, in particular, the timing. In Indonesia, as in most countries that execute, death row is little more than a grim lottery.

Tim Lindsey is Malcolm Smith Professor of Asian Law and Director of the Centre for Indonesian Law, Islam and Society at the University of Melbourne. This article was originally published on The Conversation on 23 January 2015. It is republished with permission.

![Malcom Turnbull and Barack Obama at the White House. Photo credit: By Official White House Photo by Pete Souza [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Malcom Turnbull and Barack Obama at the White House. Photo credit: By Official White House Photo by Pete Souza [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/lobbying-351x181.jpg)