What should we expect in Myanmar in 2015?

Myanmar’s prospects for future reform are looking more robust.

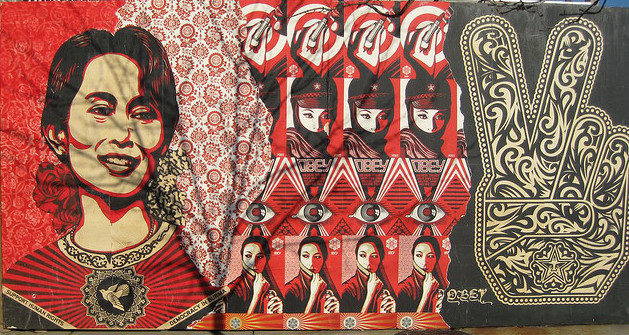

Two critical observations can be made about Myanmar as we enter 2015, the year when Myanmar’s first election is to be held after both the end of the military regime and the start of political and economic reforms in 2011. The first is that Myanmar’s reform process is still essentially on track, despite criticisms from political opponents of the former military regime—ranging from Daw Aung San Suu Kyi herself to the international human rights groups that have always associated themselves with “democratic reform”. The second is that none of the main political groups have walked away from the broad “reconciliation” process—neither the army, nor any major political party, nor any major ethnic group.

Moreover, there is no sign at this stage that efforts aimed at political reconciliation have run into “life-threatening” crises, or that they face collapse as we proceed towards an election at the end of 2015. There is no split in the army or the “military” leadership (including speaker, former general, Shwe Mann). Nor is there any significant fraying in the government-led peace process, although most parties remain dissatisfied with the results achieved (or not achieved) so far. Peace is proving very hard to tie down, but this is hardly surprising given that more than 20 different groups are involved and that this is the first time that they have all been at the same table with the same agenda and the same interlocutors.

Not surprisingly, in 2015 most attention in Myanmar will be focussed on the elections. Political activists of all stripes will be working hard to ensure the elections are not only free and fair, but also as inclusive as possible. Policy issues will hold less attention than personalities and the parties themselves. So it may be unrealistic to expect any significant new policy developments or reforms in 2015. This is not to say that Myanmar’s reforms are stalled or being reversed, although some reforms are not working as well as they might.

Unfortunately, it is unclear whether 2015 will see a breakthrough in Myanmar’s complex peace negotiations, where many issues are still to be settled, and enormous gaps to be bridged. We should not forget that these groups have never all sat down together before. Indeed, it would be a challenge for any country to resolve all problems in a mere three years! But on the whole, it is not likely that existing ceasefires will break down or that civil war and insurgency will erupt again on different fronts simultaneously, as have in the past. In other words, one can quite reasonably hope that a nation-wide peace agreement will be reached after 2015—if not before. But all participants in the peace negotiations will also need to think seriously about the larger, and more sustainable future; they may not be able to secure everything they hope for; and changes in mindsets and some compromises may have to be made all round.

On the other hand, parliamentary democracy has been restored successfully in Myanmar and the institution of parliament is strengthening day by day, is healthier than ever before, and, on present indications, is unlikely to falter. In addition, many political freedoms (freedom of expression, freedom of assembly) have already been introduced, and while not perfect, they are not really threatened either. Significant economic reforms have also been introduced, and are gradually bedding down effectively.

The reform process is far from complete and much unfinished business remains—from land rights, to restoring human rights, to reducing the role of the military, to resolving the issue of minorities like the Rohingya. These are, by their nature, harder reforms to accomplish, but more importantly they are reforms on which the Myanmar people themselves have to determine where they wish to go. Reforms in these areas cannot be imposed from outside. Yet, international assistance and expertise could be enormously helpful in assisting Myanmar to make real progress in these more difficult areas. At this point, while the Myanmar leadership wishes to determine how and when they introduce these reforms, they are still listening to outside views and advice.

Key to this, of course, is what the Myanmar people themselves think and the changes to which they aspire. One of the first nation-wide public opinion polls in Myanmar to shed light on such matters was recently published by the Asia Foundation, a non-profit international development organisation, headquartered in San Francisco, which has undertaken a number of substantial research projects since starting an active program in Myanmar in recent times. Entitled Myanmar 2014: Civic Knowledge and Values in a Changing Society, its most significant conclusion was that more than 60% of Myanmar people remain positive about the direction their country is headed, and almost 80% believe elections will bring positive change.

Myanmar’s prospects for reform remain good, even though the reforms still have a long way to go, and there remain large problems, such as land reform and reducing the role of the military in the nation. But on the whole, the Myanmar Government has so far pursued their reform process through largely peaceful means, through relatively inclusive and consultative processes, and tried to listen to the expert views of people inside and outside the country. We should not underestimate the extent of the restraint being shown by the army in not blocking reform or insisting on getting its own way.

We should also expect 2015 to bring some setbacks, but these should not be allowed to derail reform or international support for reform. Certainly everything may not be all smooth sailing, and some less-than-perfect arrangements may have to be tolerated for a while. While it may not be a time for big new initiatives, as long as the relative tranquillity that has been achieved is not jettisoned for short-term advantage by any party, the prospects are that a long-term, home-grown Myanmar political settlement may survive.

Trevor Wilson is Visiting Fellow, Department of Political & Social Change, ANU. This article can be republished with attribution under a Creative Commons Licence.