The ASEAN Summit and the Disregard of Rohingya Refugees

ASEAN has a critical role to play in the crisis facing the Rohingya people in Myanmar, with its annual summit over the weekend an opportunity to help. From the summit’s statement, it’s clear it didn’t.

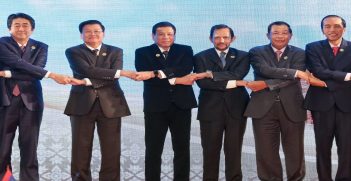

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) held its annual summit in Bangkok over the weekend. It came at an important time. There are currently more than a million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, most of whom fled a brutal campaign of violence by the Myanmar military — the Tatmadaw — in late 2017. They can’t return to Myanmar because of the ongoing violence in Rakhine State and fear of persecution.

The military crackdown in Rakhine in 2017 received a lot of attention, and a UN fact-finding mission found that there were reasonable grounds to conclude that the Tatmadaw committed war crimes, crimes against humanity and possibly genocide. It recommended that the situation be referred to the International Criminal Court (ICC). That is unlikely to happen, because only the UN Security Council can refer something to the ICC, and China would almost certainly veto any proposed action against Myanmar. The UN Human Rights Council has set up a body to collect and preserve evidence for possible future prosecution, but without the Security Council on board, there is only so much the UN can do.

So ASEAN has a critical role to play. ASEAN exists, according to its Charter, to “maintain and enhance peace, security and stability … in the region,” and to “promote and protect human rights and fundamental freedoms.” It aims to respond to “crisis situations affecting ASEAN in a timely and effective manner.”

The crisis facing the Rohingya people in Myanmar is a test for ASEAN. So far, it has not managed to do much other than make bland statements of support for the Government of Myanmar, seemingly constrained by staunch adherence to its principle of non-interference. The weekend’s summit was an opportunity for it to do more.

It didn’t.

Much of the outcome statement looked like a cut and paste from previous years: expressing support for Myanmar’s commitment to ensure safety and security; “looking forward” to the implementation of the agreement between Myanmar and the UN regarding the return of refugees; stressing the need for a “comprehensive and durable solution to address the root causes of conflict;” and affirming “ASEAN’s support for Myanmar’s efforts to bring peace, stability and the rule of law.” Nothing about accountability for perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity and possibly genocide, nothing about the ongoing violence and human rights violations, and nothing about the fact that humanitarian aid agencies are being denied access to communities in Rakhine. It didn’t even use the word “Rohingya,” buying the Government of Myanmar’s line that these people don’t exist as an ethnic group.

Despite international attention to the crisis in Myanmar over the past year, there has been no substantial change to the underlying issues that have fueled the crisis, and no substantial progress towards accountability for the crimes against the Rohingya. Following a recent visit by the UN fact-finding mission to Bangladesh and neighbouring countries, the head of the mission described the situation as being at a “total standstill.” The conflict between the Arakan Army and the Myanmar military in Rakhine has intensified in recent months, killing and injuring civilians and displacing tens of thousands from their homes. Humanitarian aid is almost completely suspended, and the Rohingya continue to face apartheid conditions. Myanmar’s citizenship law does not recognize them as citizens, meaning that they cannot access their rights on an equal footing with the rest of the population. Many of the Rohingya live in deplorable conditions in internment camps, prevented from accessing fields or markets, subject to curfews and unable to access quality healthcare and education. The Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are unlikely to want to return to Myanmar until things change.

So what more could ASEAN do?

As an absolute minimum, it should ensure that the statements of its high-level forums align with its commitments. In circumstances where the military of an ASEAN member state has been credibly accused of human rights violations, and is unwilling to hold perpetrators to account and to address the underlying issues that deprive a significant proportion of its population of their human rights, silence from ASEAN amounts to a blatant contravention of its commitment to protect human rights: let alone its commitment to respond to crises. The statements of high-level forums should call the crisis in Myanmar for what it is, and should — of course — acknowledge the existence of the Rohingya people. They should call on the Government of Myanmar to end the violence, allow humanitarian access, enable the safe, voluntary and dignified return of refugees, and submit the crimes against the Rohingya to the ICC.

At a recent conference, someone who knew ASEAN very well said “I can’t tell you how many times ASEAN leaders have told me they want ASEAN to succeed so that the UN has one less region in the world to worry about.” ASEAN’s not currently on track to achieve this, and the weekend’s statement didn’t help.

Rebecca Barber is an associate lecturer in Humanitarian Studies at Deakin University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.