Strategic Update Underscores the Strong Alignment of Australian and Japanese Strategic Objectives

Three important questions arise from the Australian government’s 2020 Defence Strategic Update in relation to Japan. How does Japan figure in the Update, how was the Update received in Japan, and how does the Update fit with Japan’s broader security strategy?

Japan figures in the Update in the Foreword where the Australian government commits to “strengthened international engagement.” It is also mentioned several times in Chapter 2 on “Defence Policy.” Here, Japan is named as an important partner alongside which “Defence will continue to work to strengthen defence and diplomatic ties with the countries in Australia’s immediate region.” The Australia-Japan “Special Strategic Partnership” is described as one of the ways in which Australia engages with bilateral partners “to support shared interests in global rules and norms,” and Japan is also noted as a participant in the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue alongside the United States in addressing “common strategic issues.” Finally, Japan is nominated as a partner with which Australia will “continue to prioritise…engagement and defence relationships” as Japan’s active role in the region is vital to regional security and stability.

Despite the fanfare with which the Update was launched in Australia, no public commentary in Japan accompanied its announcement, apart from a couple of factual reports. Nevertheless, former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo expressed his strong support for the Update in a video teleconference meeting with Prime Minister Scott Morrison on 9 July. The subsequent report of their discussion included references to the Special Strategic Partnership, the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue, and a “further broadening and deepening of the defence and security relationship.”

The 2020 Japanese Defence White Paper published on 14 July did not mention the Update, although there were references to Australia. Where the White Paper outlined Japan’s National Security Strategy, for example, Australia was listed along with South Korea, the ASEAN countries, and India under the heading “Strengthening Diplomacy and Security Cooperation with Japan’s Partners for Peace and Stability in the International Community” with a view to enhancing cooperative relations with these countries.

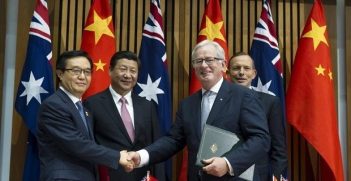

It is also worth noting that Japan’s 2018 National Defence Program Guidelines rank Australia as “second only to our formal ally the United States in terms of its strategic importance to” Japan. Since the upgrading of Australia’s security cooperation with Japan to the Special Strategic Partnership in 2014, military-to-military ties and broader security links between the two countries have expanded considerably, with the Update promising to push this process even further and faster. In fact, the pace of developments affirming the direction for the Australia-Japan defence relationship laid out in the Update has been rapid.

A week after its release, Japanese Defence Minister Kono Taro participated in a video conference with US Secretary of Defence Mark Esper and Australian Defence Minister Linda Reynolds. They agreed to oppose strongly any coercive action to change the status quo in the South and East China Seas. They also confirmed close cooperation in ensuring freedom of navigation and overflight in the region. Ten days after the Update’s release, Abe and Morrison announced a national space agency partnership with a joint statement that elaborated extensively on the growing resolve of both nations to resist militaristic expansionism in the Indo-Pacific, including in the East and South China Seas. Then at the end of July, in the statement coming out of the Ausmin talks, Japan was cited as one of the “partners” with which the United States and Australia were working to strengthen their networked structure of alliances and partnerships to maintain an Indo-Pacific region that was secure and rules-based.

Overall, the Japanese assessment of the Update will have been very positive given the extent to which it aligns with Japan’s own security and foreign policies and priorities. Clearly, Australia is a security partner that shares many of the same strategic interests and is committed to increased regional engagement. All this fits nicely with the hedging strategy adopted by Abe, which new Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide will also support. The strategy hedges against any decline in the US commitment to defend Japan and the liberal international order by expanding Japan’s own defence and deterrence power as well as its contribution to the US alliance, at the same time as multiplying its security partnerships across the region. Japan’s Ministry of Defence will also have been encouraged and reassured by the capability commitments announced under the plan. Japan welcomes a more militarily capable Australia, particularly one that can project power further from its shores.

The Update also affirms Australia’s continuing willingness to be an active and vocal advocate for a rules-based international order, which is a central principle of Japanese foreign and security policy. In particular, Japan can count on Australia’s continuing support for the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) vision, a central pillar of Japanese regional security policy, which aims to reinforce cooperation with the US, Australia, and India on the basis of this concept. In a phone call soon after Suga became prime minister, he and Morrison confirmed the importance of realising the FOIP, and Suga also affirmed during his first phone call with Trump that he would advance the two countries’ shared vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific in partnership with Australia, India, the ASEAN nations, and other countries in the region. Japan’s new defence minister, Kishi Nobuo, has stated that he hopes to step up Japan’s defence cooperation with the United States, Australia, and India by increasing joint drills and technical cooperation under the FOIP concept.

In early October, the foreign ministers of Australia, Japan, and India and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo representing the so-called “Quad” – the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue – met for talks in Tokyo. The Quad is an informal strategic forum of the four countries that holds semi-regular, high-level dialogues. For Japan, the FOIP and the Quad complement each other. The FOIP concept provides “a framework within which the Quad can clarify its roles and objectives,” and functions as a policy coordination mechanism for achieving FOIP objectives – in essence, an “international order based on rules, including the rule of law and freedom of navigation.” All four nations have affirmed the importance of this.

Furthermore, given the Update’s commitment to prioritising defence relations with Japan, it will be an important partner in an ever-increasing number of military exercises. Since the publication of the Update, Australia has participated in a trilateral naval exercise with Japan and the United States in the Philippine Sea in late July and then RIMPAC in August, which focussed on ensuring that the Indo-Pacific remains “free and open.” It is now scheduled to join, for the first time, the next Malabar trilateral maritime exercise involving the United States, Japan, and India in November. This will mean recruiting all four Quad members into a de facto Quad naval exercise reflecting, to some extent, a military operationalisation of the Quad.

From the perspective of possible future prime minister and former defence minister Ishiba Shigeru, Australia is seen as a potentially key member of an East Asian version of a NATO-like alliance mechanism, which would upscale strategic partnerships to something approximating a military alliance committed to collective defence. Although Suga has shown no interest in the concept, he is pushing his own watered-down version by signaling a willingness to work closely with Japan’s Quad partners as a top priority. Certainly, one Japanese commentator has referred to Japan’s relations with India and Australia as a “quasi-alliance,” given the levels of military-to-military and security cooperation. Moreover, Japan has taken a major step in this direction by agreeing to work with Australia on the implementation of provisions for the Japanese defence forces to protect the Australian military with the use of weapons.

In conclusion, Australia and Japan, as middle powers in the Indo-Pacific, are progressing on a course of ever-stronger strategic enmeshment, and the 2020 Defence Strategic Update has both affirmed and advanced this process. It is underpinned by the strong alignment of Australian and Japanese strategic objectives in the Indo-Pacific, which, to some extent, are playing out in Quad meetings and activities. Japan and Australia are boosting their military-to-military ties as well as their bilateral and multilateral security cooperation to an unprecedented level.

Aurelia George Mulgan is professor in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, Canberra. Her research touches on many aspects of Japanese politics, political economy, and foreign and defense policies.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.