Popular Culture and IR after Game of Thrones

Series like Game of Thrones and Lost don’t simply mirror politics in the real world. They show how pop culture makes world politics by premediating what is to come.

With the series finale of the long-running HBO series Game of Thrones now a historical event, it is worth taking stock of popular culture’s contributions to, intersections with and constructions of International Relations (IR). While various forms of popular culture have long been recognized as holding up a mirror to world politics, from the James Bond film franchise to Captain America comic books, it is a more recent recognition that popular culture makes world politics.

Undeniably, the links between the popular and the political have grown denser over the past three decades. The 1980s — which saw the former Hollywood actor Ronald Reagan in the White House — marked a watershed, from Live Aid in 1985 to the flurry of late-Cold War cinema including Red Dawn, Rocky IV, Rambo III and The Hunt for Red October to the explosive popularity of G.I. Joe toys. After a cooling down period associated with the America’s “unipolar moment,” the 9/11 attacks prompted a revitalization of popular culture’s contributions to the way we see the world, and especially our place in it: this was especially true with the medium of television.

Premiering in 2004, the global hit Lost riveted audiences around the world; as I have argued elsewhere, this series helped Americans make sense of a post-9/11 world, while also giving the rest of the globe the ability to look inside the “American mind” in the wake of the al-Qaeda attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon. In addition to its geopolitical content, Lost benefited from the advent of a host of new technologies which expanded the reach and resonance of older forms of popular culture, including DVRs and downloadable episodes on platforms like iTunes. The series took place — through flashbacks — in multiple languages and countries, including Iraq, South Korea, Nigeria and Australia. Buttressed by the availability of fast-evolving social media tools that allowed viewers to exchange information, discuss plot lines, advocate for their favourite characters, and educate themselves about the complex politics of the series, the series sculpted a global imaginary that truly resonated with its viewers, creating one of the most watched and talked about shows of the new millennium. While it has taken some time for Lost to be recognized for its contributions to the understanding of the “way the world really works,” this was obvious from the moment the next global phenomenon in dramatic television aired on 17 April 2011.

Premiering nearly a decade on from 9/11, Game of Thrones (GoT), an epic screened fantasy based on George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire novels, presented a Second Order World of the first order, prompting IR professor and political pundit Daniel Drezner to declare that we had entered a “golden age” of IR television programming. Drezner, as well as other IR scholars who have engaged with the series, tend to focus on the complex ways in which the various “houses” of Westeros clamour for power: which can be read rather easily through the lens of IR theory. The introduction of airborne, fire-breathing dragons under the control of the “breaker of chains” Queen Daenerys Targaryen and the reverse-engineering of one of these beasts by the Night King — the first White Walker, a species of undead from the frigid north who command an ever-expanding army of mindless “wights” — presents historians of world politics with an especially fecund space of representation to discuss the US development of atomic weapons, quickly followed by the Soviet Union — using intelligence gleaned from Los Alamos and elsewhere. Given the popularity of the series, lecturers of IR across the US, UK, Australia, and other member states of the western alliance were quick to fold the series into their courses, eager to make use of their students expanding knowledge of “hard” and “soft” power in the fantasy-land that they entered each week, or more likely in prolonged “binges.”

Looking beyond these metaphors, the series — which is set in a world of two continents, a Britannia-like Westeros and a Levantine/Asiatic realm of Essos — revels in Orientalist stereotypes, screens a violent misogyny, and trades in various tropes of “whiteness” and “northernness.” Arguably, these have partially fuelled the current lurch to identitarianism, new forms of patriarchy, and anti-immigrant sentiment across the western democracies. As a point of reference, the most popular — and ultimately victorious — family in the series, the Starks, advocate for decentralised government, a return to the traditions of the past, and constant securitization against threats both internal and external: sound familiar?

Despite the arch-conservative grounding of the series, GoT has also been lauded for engaging the ontological insecurity of the developed world vis-à-vis the looming impacts of climate change in its central theme of “Winter is Coming!” which inverts the threat of global warming by scripting a permanent winter, more akin to that promised in the event of a full-scale nuclear exchange. This verbal meme, which can used in almost any social setting, refers to the threat of catastrophic climate change, which is brought on by the White Walkers, who — at least in the series if not the books — were created as a last ditch effort by the Children of the Forest, an otherworldly non-human race resembling the aos sí of Irish mythology. Whatever the merits of Martin’s meticulously built-world’s introduction of the threat of the climate crisis into the everyday lifeworlds of GoT viewers, the resolution of the epic wrapped up things too neatly, with the White Walkers dead, climate change averted, and the happy denizens of Westeros ruled by a benevolent monarch who will ensure that neoliberal prosperity continues.

In their own ways, these two series changed television viewing forever: first by creating space for high-quality, attention-demanding, and geopolitically-engaged drama in Lost, and then by taking full advantage of the new milieu, at least in terms of metaphor, in Game of Thrones. Taken in concert, they have prepared a new generation of small screen enthusiasts for content that not only reveals and contests the vagaries of world politics, but also premediates what is to come, therein preparing the ground for substantive changes in power relations, as well as political culture.

We should not view the conclusion of GoT as an end, but as a transition to a new stage of televisual IR. Geopolitical television is now all the rage. Across Scandinavia, public broadcasters are producing sophisticated series that deal with everything from petro-politics in Norway’s Occupied and Nobel to the rise of radical right/left politics in Sweden’s The Bridge and Blue Eyes, to the blowback of participating in Middle Eastern conflicts seen in Denmark’s Below the Surface and Warrior, and to China’s creeping influence in the Arctic in Iceland’s Trapped and Stella Blómkvist.

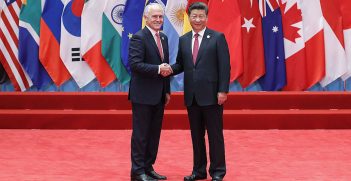

Two recent Australian series, Secret City and Pine Gap, have also reflected the rising power of Beijing, while also critiquing the unbalanced relationship between Canberra and Washington in the post-Cold War era. Elsewhere, historical dramas are serving a tool for revising and reimagining how we got to where we are, including The Crown (UK), Rebellion (Ireland), Deutschland 83/86 (Germany) and Netflix’s noir-ish alternative history 1983 (Poland). Bubbling fears around the issue of migration are perhaps the area where we seeing televisual interventions most obviously coming to the fore, with Safe Harbour (Australia), Taken Down (Ireland) and Pagan Peak (Germany/Austria) tackling the issue head on. At the same time, existential worries about humanity’s capacity to alter the world also permeate contemporary TV series, resulting in the increasing popularity of “pandemic” dramas from AMC’s paranoia-inducing The Walking Dead to the UK’s Fortitude to the Danish-Swedish The Rain.

Perhaps, this moment represents a threshold that portends a deepening nexus of popular culture and world politics. This should not surprise us given that a former reality-TV host occupies the Oval Office and the newly-elected president of Ukraine came to fame playing that role on television. Popular culture — especially in a world of Netflix, SBS on Demand, Amazon Prime, and other transnational digital providers — matters.

Professor Robert A Saunders is a researcher in the Department of History, Politics and Geography at the State University of New York (SUNY). He is the author of four books, including Popular Geopolitics: Plotting an Evolving Interdiscipline (Routledge, 2018). His research explores the impact of popular culture on national, religious, and political identities in the 20th and 21st centuries.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.