Nigeria’s 2023 Presidential Election: Hopes and Trepidations

The choices for the next president of Nigeria are stark and few. Moving beyond the turmoil of insecurity, poverty, government largesse, and anaemic economic growth will require a bold leader, not more of the same.

Nigerians will head to the polls on 25 February 2023 to elect a new president. It will be an epochal election, considering the high expectations and trepidation expressed by Nigerians about the new president’s ability to address the country’s longstanding socio-economic problems. Regardless of who prevails in the election, their swearing-in ceremony on 29 May will be devoid of the lavish pomp and pageantry that usually accompanies the inauguration of a new administration in Nigeria. The mood will indeed be very sombre, with no popping of champagne and floating of balloons, as beleaguered Nigerians anxiously wait for the new president to announce his plans for salvaging them from many years of socio-economic deprivation.

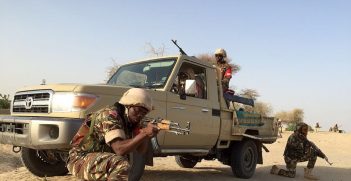

A major dilemma the new president will contend with in the first hour is insecurity. Except for a few pockets of the country, like the capital city Abuja and metropolitan Lagos, much of the country is traumatised daily by ransom-seeking kidnappers, terrorists, cultists, separatist movements, herders-farmers conflicts, and other violent criminals. As of November 2021, three million Nigerians were displaced from their homes by Boko Haram and other non-state armed groups, particularly in the northeast and northwest parts of the country. Many areas of the south and southeast regions of the country are off limits to travellers, tourists, and businesspeople due to random violence. Naturally, this has impacted Nigeria’s productive capacity and has exacerbated the country’s already high unemployment, poverty, and inflation rates. Meanwhile, violence appears to have escalated as the presidential election approaches, spurring speculation that the polls might be postponed for security reasons. Addressing these issues will be an uphill task, particularly considering that the outgoing President Muhammadu Buhari, a retired two-star general, has made little progress across eight years in office.

It would be almost impossible for the new president to address Nigeria’s high poverty, unemployment, and inflation rates without first securing the country. Poverty in Nigeria is very grim, a paradox that the new leader of the oil-rich country will find very challenging to obviate, at least in the short term. About 47.3 percent of Nigerians, or 98 million people, live in multidimensional poverty. The Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) has the number at 40 percent or 83 million Nigerians – a rate that is far higher than those of some oil-producing developing countries like Brazil (9.1 percent), Mexico (6.5 percent), Ecuador (9.7 percent), and Iran (3.1 percent). Nigerians have also been hit by intolerably high unemployment (33 percent; 43 percent for youths) and inflation rates (21 percent). Because the country’s inflation is driven mainly by high food prices, many Nigerians face the risk of hunger and malnutrition. Unfortunately, the incoming president will inherit a weak macroeconomic environment that will make it difficult to address these economic challenges.

The economy grew at about 3.2 percent in 2022, but the International Monetary Fund expects a lower growth rate of about 3 percent during the first two years of the new administration. This economic growth rate is grossly insufficient for significantly reducing the country’s high poverty and unemployment rates. The Chinese experience suggests that Nigeria should grow at between 8-10 percent annually to bring the poverty rate down to a single digit. This looks extremely difficult in the short term due to the lack of security, but also poor infrastructure, institutional weaknesses, and fiscal challenges.

Nigerian youths are very anxious about the next president. They have been involved in politics at a rate never seen before in the country. Apart from the #EndSARS protests in Nigeria in October 2020, which saw millions of youths across Nigeria protest police brutality and economic deprivation, Nigerian youths are increasingly becoming vociferous in the country’s socio-economic and political affairs. This means that whoever becomes president must pursue youth-friendly policies and assuage the pent-up anger produced by them. The incoming president must therefore get his economic policies right or risk an implosion reminiscent of the Arab Spring.

To be sure, with the country’s tight fiscal environment, pursuing youth-friendly policies won’t be easy. Nigeria has been grappling with low revenue, spiralling deficits, and debts due in no small amount to shortfalls in oil production and the poor performance of the non-oil sectors of the economy. Nigeria’s revenue-to-GDP ratio was 7 percent in 2021 and was among the five lowest in the world. By May of this year, revenue-to-GDP ratio is expected to be below 10 percent. According to economists, a revenue-to-GDP ratio above 15 percent is a precondition for economic development, job creation, and the provision of essential social services. Low revenue means that the new government will continue with the practice of the outgoing Muhammadu Buhari administration in borrowing to finance budget deficits. In his 2023 budget, for instance, Buhari proposed to spend ₦20.51 trillion Naira (US$43.7 billion), with a deficit of ₦10.78 trillion to be financed with ₦8.80 trillion in new borrowings. This will only get worse unless drastic measures are taken to rein in spending. On top of this, Nigerians have become very wary about deficits and debts, and the incoming president will likely have a harder time than his predecessors in using debt to finance development projects, as public opinion will likely work against that approach.

There will be two litmus tests for determining the new president’s tenacity in addressing Nigeria’s fiscal quandary. The first is their ability to confront the country’s hugely expensive, corruption-ridden, and unsustainable fuel subsidy. The fuel subsidy, which has been in place since the 1970s, cost the Finance Ministry US$10 billion in 2022. This amount is expected to rise to $16.2 billion in 2023, unless the new president jettisons it. Previous governments attempted to remove the subsidy, but back-peddled after massive protests. Given Nigeria’s dire fiscal situation, it is doubtful that the incoming president will have the option. Nigerians are likely to be more understanding if subsidy removal spurs strong economic recovery, structural transformation, and inclusive economic growth that can be felt across a broad swath of the Nigerian society. Removing the subsidy will free up funds for supporting productive and employment-generating sectors of the economy like infrastructure, agriculture, agro-processing, labour-intensive manufacturing, and information communication technologies. It will also reduce the need for borrowing to finance budget deficits.

The second test is whether the incoming president can reduce the high cost of governance in Nigeria, a major contributor to deficits and debt. Nigeria’s National Assembly, made up of the Senate and House of Representatives, is bloated. The 36 states that make up the federation also have their State Assembles. Members at both the national and state levels have a retinue of aides, all of whom are on the government payroll. In addition to their huge allowances, members of the national and state legislative bodies receive humongous funds for “constituency projects,” as well as estacodes in foreign currencies for numerous foreign trips. These have got to be scaled back if Nigeria is to return to fiscal sanity.

In conclusion, it is very unlikely that a business-as-usual president will be able to decisively take on Nigeria’s socio-economic problems. The new president should be willing to leave an indelible legacy of bold and effective economic policies that extricate most Nigerians from poverty and unemployment, while also securing and unifying the country.

Dr Steve Onyeiwu is Professor of Economics, Allegheny College, Meadville, Pennsylvania, USA.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.