Astropolitics of the South Pacific

Australia and New Zealand are increasing their activities related to outer space. Still, they are not the only countries in the region doing so.

Location is key when it comes to activities related to space. It takes much less energy, and therefore money, to launch a rocket to space from the equator, which is why most rocket launches within a country are done from the closest point to it. Popular rocket launch sites can be found in places like Texas, Florida, Kazakhstan, French Guyana, and Hainan.

Yet an American-New Zealand company, Rocket Lab, keeps launching rockets from New Zealand, which is located at the bottom of the South Pacific region, far from the equator. This is because its geographical position offers other advantages. Apart from the low levels of air traffic, New Zealand enjoys low light pollution, a wide choice of launch angles, low population density, and is in a geopolitical area with limited political tensions. Compare this with the neighbouring North Pacific region, where China and the United States are fighting for global hegemony. But New Zealand is not unique in this regard.

Many other South Pacific nations also enjoy such geographical and political advantages. Australia has sparsely populated territory near the equator – that is why NASA chose Australia’s Northern Territory to launch a rocket last June and Japan landed a space mission carrying samples from an asteroid on the Woomera Prohibited Area, about 500 kilometres northwest of Adelaide in 2020.

The rest of the South Pacific region is also actively engaged in space-related activities. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi acknowledged in 2014 the role played by Fiji in the success of India’s first Mars mission and offered to make Fiji the hub for regional collaboration in space. This February, Elon Musk offered his Starlink satellite constellation to help re-establish communications in Tonga after the volcanic eruption and tsunami. A SpaceX team went to Fiji to establish a station to help reconnect Tonga. Separately, a United Nations (UN) team also provided small satellites and other telecommunications support to re-establish communications.

The government of Tonga has formed international partnerships with the United Kingdom Space Agency and the British Renewable Energy Space Analytics Tool (RE-SAT) to support the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. This is critical infrastructure for Pacific nations not just to fight climate change but to secure self-sufficient energy supplies.

French territories in the Polynesia have been used for satellite tracking as well, not just by France but also the US and even Ukraine. Niue has received formal accreditation from the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) as an International Dark Sky Sanctuary and International Dark Sky Community, which covers the whole country with Dark Sky protection and recognition, making it an ideal spot to observe space. In the Cook Islands, a start-up company has used dishes to connect outer Pacific Islands to the worldwide web using satellite technology. Another start-up called Emstret is disrupting the local internet in Papua New Guinea’s market by offering cheap satellite broadband run by solar-powered Wi-Fi systems.

Convenience flags

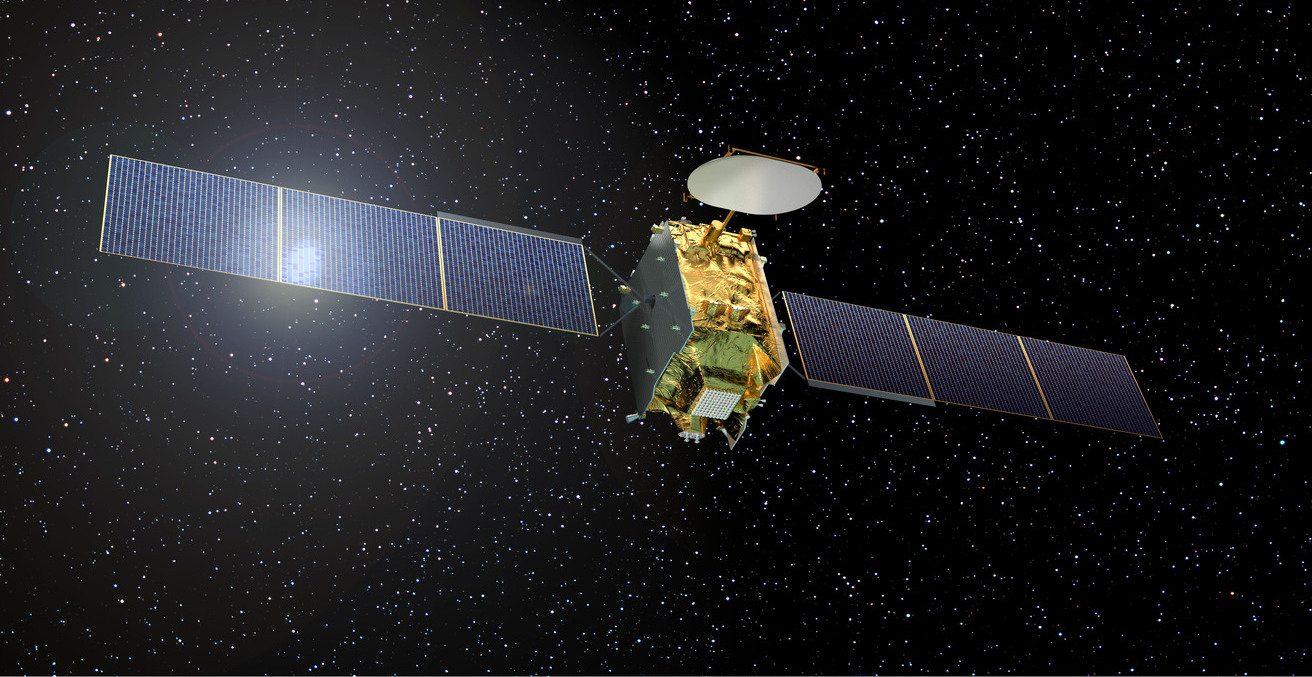

In some ways, navigating space is similar to navigating the ocean. Apart from having to deal with space weather and gravitational pulls similar to sea currents, “ships” must be registered under a flag to navigate the stratosphere. Every single satellite needs to be registered under a country, just like when navigating international waters. If it is amusing to see a ship flying the flag of a landlocked country, such as Switzerland, it is also quite interesting to witness satellites that are registered to countries with no space agency, such as Tonga. However, the experiences of Tonga and PNG demonstrate the inadequacy of current international law to address the registration of objects in space.

Tonga’s national satellite operator, Tongasat, rents its satellite slots to foreign companies, mostly from China such as APT Satellite Holdings or CESEC. Still, these links with China have come with a bit of a political turmoil. In 2018, the prime minister of Tonga and the Public Service Association sued Tongasat and the government over payments made to Tongasat by China without government approval.

Papua New Guinea (PNG) also attempted to rent its satellite slots to foreign companies do the same, but it resulted in different outcomes. In 2021, the US company AST & Science had an ambitious but problematic business plan to provide PNG with mobile internet using 243 gigantic satellites, each with a cross-section of 450 square metres. NASA initially filed a report raising significant concerns with the project, arguing that the number and size of the satellites in the AST & Science constellation posed a significant risk and would cause NASA to experience significant satellite conjunction.

But the greater problem was that rather than seek a license directly from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the US for their enormous satellites, AST & Science received a license for its system from PNG. This was more than a “flag of convenience” situation as PNG did not accept international responsibility or liability for the activities of commercial entities it has licensed. Under the Liability Convention, countries agree to be liable for any damages caused in space “due to its fault or the fault of persons for whom it is responsible.” AST & Science admitted to the FCC that PNG did not sign the space Registration Convention but claimed that PNG would voluntarily register the constellation. However, voluntarily registering the constellation is not the same as taking legal responsibility for it. In the end, PNG did not assume the potentially huge liability of a collision, as PNG’s entire governmental budget is less than AU $9 billion, and the value of the satellites in the 700-kilometre orbit easily exceeds AU $15 billion.

Opportunities come with risk

As we have seen, space ventures bring different types of opportunities. Recently, Australia and New Zealand together with the US, the UK, Canada, France, and Germany signed the Combined Space Operations Vision 2031 Statement with the aim to share information about space operations and activities and coordinate efforts. At the same time, the statement set out common principles and objectives in relation to space security. But closer defence alignment in space with other Western nations might collide with Chinese interests, and let us not forget that China is the main trading partner of both Australia and New Zealand.

Smaller island nations are finding opportunities in satellite technologies. Imaging for helping disaster relief, better internet connection, and satellite tracking stations provide both business opportunities and political leverage. But commercial space legislation is still not quite established, and future mitigation and avoiding conflicts in space need robust public-sector support from these island nations to make these opportunities happen. Current space legislation dates from the 1960’s and 1970’s and does not contemplate current private commercial activities. At the same time, new initiatives such as the Artemis Accords have just been signed by 21 countries, and space powers such as China, Russia, and India are not among them.

A new age of exploration is emerging for this region of navigators. The coming years will test their sailing skills.

Marçal Sanmartí is a researcher at the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs where he does analysis about the politics of outer space or Astropolitics. He also has collaborated with the Catalonian Global Institute, Espai.media, and the Space Review. He is a member of the Planetary Society.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.