Calls for Australia to provide greater reassurance to the US reflect valid concerns about maintaining a strong alliance, but that reassurance should be mutual—not one-sided. Canberra faces the challenge of aligning closely with Washington while preserving its own autonomy, national interests, and regional diplomatic relationships.

Calls for Australia to do more to reassure Washington have some merit, but primarily as a matter of signalling resolve rather than deference. If US commitment to the region is perceived as uncertain, reassurance must be reciprocal, based on trust and policy clarity. Canberra’s priority is not to appease an unpredictable ally but to protect its own interests through credible defence capability and diversified partnerships, as well as diplomatic autonomy. If reassurance is to carry weight, it cannot be one-sided.

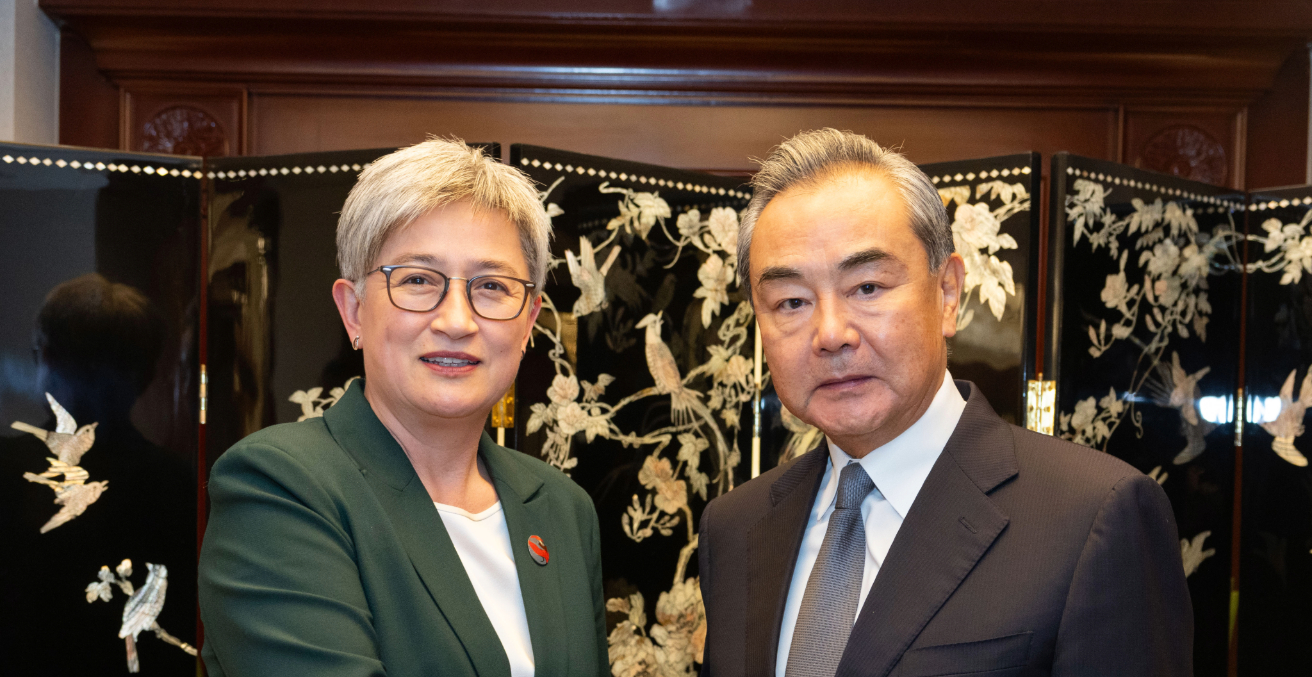

Australia’s relationship with China underscores the complexity of this balancing act. After years of strained ties marked by trade sanctions and diplomatic hostility, the Albanese government has sought to ‘stabilise’ relations with Beijing without compromising core security priorities or democratic values. China remains Australia’s largest trading partner and restoring dialogue has been essential for economic resilience. This pragmatism reflects the logic articulated by Richard Armitage, Deputy Secretary of State under George W. Bush: “Diplomacy is much more than just talking to your friends. You’ve got to talk to people who aren’t our friends, and even people you dislike. Some people…think that diplomacy is a sign of weakness. In fact, it can show that you’re strong.”

Engaging with Beijing does not mean overlooking disputes on security or human rights; it is simply a recognition that managed dialogue can reduce the risks of miscalculation in a volatile region. This approach is particularly relevant in light of the most recent targeting of overseas pro-democracy activists—including an Australian academic—by Hong Kong authorities under its national security legislation, a move that has deepened concerns among democratic nations about the extraterritorial reach of Chinese law. Such actions form part of a broader pattern of transnational repression, where Beijing seeks to silence critics and intimidate diaspora communities beyond its borders, raising serious questions about the sovereignty of other nations and the safety of their citizens. When coupled with China’s ongoing militarisation of the South China Sea, its state-sponsored cyber intrusions and its readiness to deploy economic coercion as a tool of political leverage, these actions underscore the difficult balance Canberra must strike between engagement and vigilance.

Domestically, however, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s efforts on this front have drawn sharp criticism. Opposition figures argue that his diplomatic overtures risk creating uncertainty about Canberra’s loyalties. His recent China visit was dismissed by some commentators as a “six-day festival of flattery,” with claims that he “dutifully tugged his forelock to Emperor Xi” and was “duchessed” in a manner that “at every level…damaged our national interest.”

Opposition Leader Sussan Ley expressed disappointment that Albanese did not extract stronger assurances from Beijing and accused Defence Minister Richard Marles of “making excuses” for the Chinese Communist Party. Deputy Opposition Leader Ted O’Brien described Albanese as “weak on security” and “more a cheerleader than a leader,” while Liberal Senator James Paterson called the engagement “a little bit indulgent.” Former Prime Minister Scott Morrison told a US congressional committee that Australia’s appreciation of the China threat “is somewhat in jeopardy” under the current government.

At the same time, US observers have questioned Australia’s reliability on AUKUS. Jerry Hendrix, a retired US Navy captain now leading the Trump administration’s push to expand the US fleet, had last year described Australia’s stance on AUKUS as “noticeably fickle.” He warned that the program faces two significant challenges: whether future Australian governments will sustain the political and financial commitment, and whether the US will be willing to release Virginia-class submarines on schedule. Pentagon policy chief Elbridge Colby has gone further, urging Canberra to “pre-commit” to potential US conflicts in the region, a demand that places considerable pressure on Australia’s strategic autonomy.

Yet Canberra, under the stewardship of both Coalition and Labor governments, has consistently demonstrated its commitment to AUKUS in the face of mounting domestic criticism. In a speech delivered by the Governor-General at the opening of the 48th Parliament this month, the Albanese government reaffirmed that AUKUS “will continue to be progressed” as part of a broader agenda to “strengthen Australia’s security partnerships.” A 50-year defence and industrial cooperation agreement has just been signed with the UK, and Australia has already contributed $1.6 billion toward Virginia-class submarine procurement, with payments on track to meet the US$2 billion commitment by the end of 2025. Indeed, AUKUS was enshrined in the Australian Labor Party’s national policy platform in 2023, signalling bipartisan resolve on the partnership.

Calls for Australia to do more extend beyond diplomacy. In May, US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth pressed Canberra to increase defence spending well beyond current projections. Colby and others argue that Australia must not only benefit from US security guarantees but also co-produce deterrence. Some make the case that Colby’s request has been misinterpreted, asserting that he is not seeking to dictate Australia’s decisions but to obtain in-principle guidance for allied planning.

This debate naturally raises questions about resources. To remain a credible partner, Australia must balance US expectations for greater capability with its own fiscal and industrial constraints. Domestically, the Opposition and conservative commentators argue that current allocations remain insufficient. Yet the assumption that Canberra can simply escalate defence outlays without consequence is questionable. AUKUS alone is projected to cost $368 billion over three decades, already straining fiscal priorities. Rapid spending increases the risk of creating capability gaps elsewhere and diverting funds from critical domestic needs. It is arguably incumbent on those advocating significantly higher defence spending to outline a credible budgetary pathway and identify the trade-offs required.

There is also a contradiction in domestic rhetoric. While the Coalition urges stronger alignment with Washington, it has also criticised some steps that seem to go towards precisely that. The Albanese government’s decision to lift biosecurity restrictions on US beef imports, following a 10-year review, was welcomed by President Trump. Yet Shadow Agriculture Minister David Littleproud stated that it “looks as though it’s [biosecurity] been traded away to appease Donald Trump.” Such reactions underscore how alliance reassurance, while demanded rhetorically, is politically fraught when it requires visible concessions.

The view that Canberra must constantly do more to reassure Washington overlooks the scale of Australia’s existing commitments. AUKUS is itself a profound signal of alignment, while partnerships with Japan, ASEAN nations and India further reinforce regional deterrence. If reassurance is required, it must be mutual: Washington must also demonstrate that it values Australia as a partner rather than as a strategic auxiliary. As Prime Minister Albanese has put it, Australia “gives and deserves respect.”

Australia’s credibility as an ally does not depend on mirroring every US preference. Effective statecraft requires both deterrence and dialogue, pursued in a way that serves Australia’s long-term interests rather than reactive reassurance.

Elena Collinson is Head of Analysis at the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney. She has previously held positions as researcher and adviser in Australian departmental, ministerial and Senate offices, at state and federal levels. She is also a lawyer admitted to the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.