Money Matters But It Doesn’t Decide: The Case of Michael Bloomberg’s Presidential Campaign

Michael Bloomberg spent nearly a billion dollars in personal wealth on an unsuccessful bid for the US presidency. While personal spending is not limited by campaign finance laws, self-funded candidates often find it difficult to win elections.

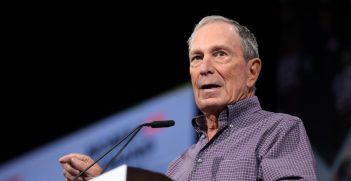

On November 24, 2019, Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City, declared his candidacy for the Democratic nomination for president. Due to his late start, Bloomberg passed on the four early contests, set for January and February, that were the focus of his rivals and targeted the sixteen nominating events set for March 3, 2020 – Super Tuesday – when more than a third of the delegates to the Democratic National Convention would be chosen. Spending lavishly from his own ample personal wealth, estimated at around $58 billion by Forbes, on advertising and field staff, Bloomberg rose sharply in the polls. On March 3, however, the Bloomberg campaign crashed and burned. He received a little less than ten percent of the total votes cast, carried just one contest, American Samoa, and won just 55 delegates of the 1357 at stake that day. On March 4, one hundred days and $875 million in spending after he began his campaign, Bloomberg withdrew from the race and endorsed his erstwhile rival, former Vice President Joseph Biden.

How could one man could spend almost a billion dollars of his own wealth on his own election campaign? What does his campaign tell us about the role of money in elections? What did all that spending accomplish? Here are some answers: Bloomberg could spend that much because U.S. campaign finance law, as shaped by the U.S. Supreme Court, allows it. Bloomberg’s campaign tells us that money matters, but it doesn’t decide elections. And although Bloomberg did not win, his speedy endorsement of Biden and his announcement that he will devote campaign funds to aiding Biden in the general election indicate some satisfaction that a centrist like himself emerged from Super Tuesday as the likely nominee.

How could Bloomberg spend that much?

Required election law filings indicate that as of February 29, the Bloomberg campaign had raised in excess of $936 million, 99.91 percent of which came from Bloomberg’s own funds, and had spent more than $875 million. The final numbers could well be higher. This appears to be, by far, the most any candidate for president had ever spent at this early stage in a presidential race, and by far the most any candidate had used to self-fund. It is also, of course, entirely legal.

In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court determined that campaign fundraising and spending are protected by the First Amendment. Campaign money could be limited, but only to prevent corruption and its appearance. Contributions to a candidate, and to groups that coordinate with or give to candidates, could be capped because they raise the danger of quid pro quo’s. But a candidate’s donation to his or her own campaign presents no danger of corruption, and so cannot limited. Nor can a candidate’s or political group’s campaign spending be limited. Communicating with the voters, the Supreme Court said, raises no danger of corruption. And inequality – the vast differences in the abilities of candidates or interest groups to raise and spend money – is not a sufficient basis for restricting constitutionally protected spending.

The Supreme Court later went even further than Buckley in protecting the right of wealthy candidates to self-fund. In the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, Congress added a measure, known as the Millionaire’s Amendment, that allowed a candidate who has a high-spending self-funded opponent to accept donations in amounts larger than normally permitted. In Davis v. FEC (2008), the Supreme Court struck down the measure, finding that it unconstitutionally burdened the First Amendment right of the self-funded candidate without advancing the prevention of corruption.

What does Bloomberg’s campaign tell us about money in elections?

Bloomberg’s campaign confirms what has long been understood: money matters but it doesn’t decide. Bloomberg’s massive spending allowed him to very quickly become a major factor in the election. Even as significant candidates like Senator Kamala Harris and Senator Cory Booker, who had been campaigning for a year, faded and dropped out, Bloomberg’s poll numbers rose steadily. By mid-February, he was ranked third and rising in most national polls, just behind Biden and ahead of Senator Elizabeth Warren, who had been a strong third for all of 2019. With more than $500 million in advertising spending – $200 million more than President Obama had spent in the entire 2011-12 election cycle – Bloomberg seemed poised to become the choice of centrist voters unnerved by Senator Bernie Sanders’s success in the first three nomination contests.

As we know, that didn’t happen for a number of reasons: Bloomberg’s “disastrous” debate performance on February 19; the new focus on the more unattractive features of his record (); and especially Biden’s triumphant victory in South Carolina primary on February 29 and the dramatic decision of the other top centrist rivals to withdraw from the race and endorse Biden on the eve of Super Tuesday. With Biden the consensus choice for moderates, Bloomberg faded.

This should not be a surprise. Self-funders can spend enough to be a factor, but usually don’t win. Only nine out of 40 self-funded congressional candidates in 2018 won, and only four of 21 in 2016. This also seems to be particularly true in modern presidential elections. The second biggest self-funder in presidential history also ran in 2020: Tom Steyer, who raised $270 million (98.63 percent self-funded). He focused heavily on South Carolina, where he won just 11 percent of the vote and no delegates – and no delegates anywhere else either. Other high-spending self-funders who fell short include Ross Perot in his 1992 independent run; Steve Forbes in his 1996 and 2000 runs for the Republican nomination; and to a lesser extent, Mitt Romney who spent $53 million to self-fund 40 percent of his 2008 race for the Republican nomination https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/02/15/us/politics/michael-bloomberg-spending.html?searchResultPosition=2.

High levels of campaign spending can get the voters’ attention and get them to think seriously about the candidate. But other factors, such as the candidate’s record, message, and personality, the qualities of the other candidates, and the decisions of important interest groups, party leaders, and the media, are also critical. Here, as in so many other ways, Donald Trump is the exception that proves the rule, and he didn’t truly self-fund. The $70 million Trump spent on his campaign was only 20 percent of his total campaign spending.

What did Bloomberg’s spending accomplish?

Bloomberg entered the race as Biden was faltering and Senators Sanders and Warren, the most left-wing major candidates, were polling strongly. Bloomberg opposed them both on policy grounds and the concern that they were too far to the left to defeat Trump. Indeed, with half his ad spending consisting of anti-Trump messages, Bloomberg’s candidacy seemed to be almost as much anti-Trump as pro-Bloomberg. To the extent his candidacy was intended to provide centrist voters with an alternative to the seemingly shaky Biden, this became unnecessary when Biden came back strong starting with South Carolina and a centrist became the likely nominee.

Underscoring his commitment to the anti-Trump cause, soon after ending his campaign, Bloomberg announced he was donating his leftover campaign funds to the Democratic party. Bloomberg’s money couldn’t win him the nomination, but it may still have the influence he wants on the general election.

Richard Briffault is the Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation at Columbia Law School in New York. His research, writing, and teaching focus on state and local government law, legislation, the law of the political process, government ethics, and property.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.