Why Some Regimes Are More Authoritarian Than Others

Malaysia and Singapore are lauded as successful examples of newly independent states that should be emulated by Third World countries. At the same time they are derided as authoritarian regimes that deny their citizens fundamental liberties. Which is correct?

There is more than a modicum of truth behind both claims: both countries have achieved spectacular economic growth at the expense of significant personal freedoms for their respective populations. However, in spite of many similarities between their political systems, there exist some differences as well—the most significant perhaps being the level of authority that each ruling regime commands. While both can be termed ‘competitive authoritarian’ regimes, Singapore evidently exhibits a higher degree of authoritarianism and control over its populace than Malaysia.

In the former, there is a much lower rate of opposition representation in the legislature; there are lesser forms of contestations to state power emanating from civil society; the main opposition does not differ from the government in its core philosophies; and the state has managed successfully to stave off challenges to its authority in a more effective and lasting manner.

At the same time, although both are heralded as successful cases of new states, Singapore has clearly outperformed its neighbour on the economic front as well, boasting one of the highest standards of living in the world. Therefore, a puzzle arises: despite featuring remarkable similarities in its approach to politics and imposing severe constraints on other actors to limit their influence in the political sphere, why is it that Singapore has been able to persistently display more authoritarian tendencies than Malaysia?

Party unity vs democracy

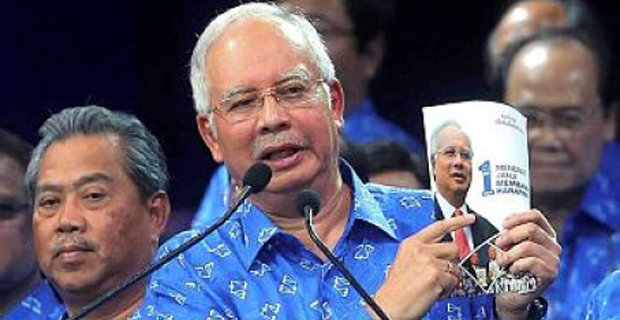

Drawing on the literature on elite cohesion and democratic transitions, I posit that the elites in Singapore have been able to be more unified and, hence, have retained greater control over their society than their Malaysian counterparts. This is possible because of the structures of the respective dominant parties in the countries. In Singapore, the People’s Action Party (PAP) regime has a party structure that resembles a cadre party, whereby leaders are selected and not elected. On the other hand, in the United Malays National Organization (UMNO)—the main component party in the ruling Barisan Nasional (National Front)—the structure is more akin to a mass party, where there is contestation for the leadership of the party.

In the case of the PAP, the party is likely to perpetuate itself, since its leaders are handpicked by their predecessors, and party ideologies and major directions are less likely to be altered significantly, even if different leaders are in charge. Additionally, there is less room for other actors within society—including opposition parties and civil society groups—to take advantage of divisions within the party, since there is no contest for the party leadership, and the party is more likely to be a coherent entity and present a unified front on most important issues.

Conversely, when the possibility of contests to the party leadership exists, such as in the case of the UMNO, factions are more likely to arise within the party such that it is not as cohesive as it could otherwise be; the likelihood of other societal actors forming pacts with key party personnel in order to undermine the ruling regime is increased; and the possibility of different ideologies being accepted by a significant portion of the populace is heightened.

Structures as an explanation

The difference in party structure is an explanatory variable in explaining why some authoritarian regimes are able to exercise more control over their society than other similar authoritarian regimes, because a party structure that promotes cooperation between elites is more likely to result in elite cohesion. Authoritarian strength is measured in two ways: first, the vote share of the ruling regime and, second, whether alternative ideologies—those which are in direct contradistinction to the ones propagated by the incumbents—are accepted by a significant portion of the masses.

In making the claim that Singapore is indeed more authoritarian than Malaysia, I draw on the following: Levitsky and Way, who consider Singapore to be a ‘borderline’ case between ‘pure’ and ‘competitive’ authoritarianism, whereas Malaysia is an outright example of the latter; the Polity IV index, which states that Malaysia is more democratic (or less authoritarian) than Singapore; and, finally, the fact that the vote shares and seat shares of the opposition in Malaysia far exceed those of their Singaporean counterparts. I do not assert that party structures are sufficient to explain the entire picture. Indeed, many authors have delved into the reasons for authoritarian durability in both countries and, in recent times, have attempted to discuss the seeming waning of the incumbent’s hegemony in Malaysia.

I accept that a multifaceted explanation is required to explicate this phenomenon fully. Various factors given in the literature—such as Singapore’s small size, the enduring influence of Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore’s founding prime minister) or the lack of societal cleavages in the country compared to Malaysia—are all relevant in explaining the ease with which the PAP has exhibited dominance over the city-state compared to its neighbouring counterparts. What I do contend, however, is that party structures are explanatory variables that have not been given due attention in analyses of these two countries, and this is what I seek to rectify. Furthermore, party structures can affect the manner in which societal cleavages are translated into political allegiances, as the various competing elites appeal to different segments of their support base.

Competitive authoritarianism

Both Singapore and Malaysia can be termed ‘competitive authoritarian’ regimes, where formal democratic institutions are widely viewed as the principal means of obtaining and exercising political authority. Incumbents violate those rules so often and to such an extent, however, that the regime fails to meet conventional minimum standards for democracy. At the same time, the rules are not violated to the extent that other actors in society cannot pose challenges to the incumbent regimes, even if the playing fields are not level.

The durability of both the UMNO and the PAP in retaining power has perplexed many scholars. Adam Przeworski and Fernando Limongi highlighted this conundrum by stating that both countries have managed to remain as “dictatorships”, despite being wealthy, while Barbara Geddes laments that Singapore proves to be a difficult case for modernisation theorists who believe that economic growth and democratisation go hand in hand. Although the use of the term ‘dictatorship’ is perhaps harsh, and I suggest that ‘competitive authoritarian’ would be more apt, the point remains that, in the grander scheme of things, Singapore and Malaysia seem to be anomalies in explaining the relationship between economic development and democracy.

I contend that a cadre party, or a party with little intra-party democracy, will likely be more authoritarian than one which incentivises intra-party dissent. This is because the former is more likely to create a more cohesive elite, whereby opposition parties and other societal actors that are opposed to the regime cannot exploit the divisions within the party. It must be noted here that I do not make the claim that elite disunity would lead to the collapse of an authoritarian regime, as asserted by Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe Schmitter, as there are other factors that matter.

The authoritarian controls the party has put in place in the system, and the ability of the opposition to break the stranglehold of the regime would also matter in causing a transition. Recent events in Malaysia have shown that the UMNO’s hegemony is indeed in jeopardy. However, although the PAP has experienced an unprecedented challenge to its authority in recent years, in the form of the Workers’ Party, its authority is very much intact, judging by its control over parliament and the strong showing in the 2015 elections. The party structures of these hegemonic parties may be a factor in their differing fates.

Walid Jumblatt Abdullah is a PhD candidate under the joint degree program between the National University of Singapore and King’s College London.

This article is an extract from Abdullah’s article in Volume 70, Issue 5 of the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled “Assessing party structures: why some regimes more authoritarian than others” It is republished with permission.