Never has the interplay of technology, media, and political power had such potential to magnify and weaponise propaganda and its sub-set “disinformation.” The times call for fresh policy thinking about how to pre-empt or minimise harm to vulnerable and susceptible communities across Oceania.

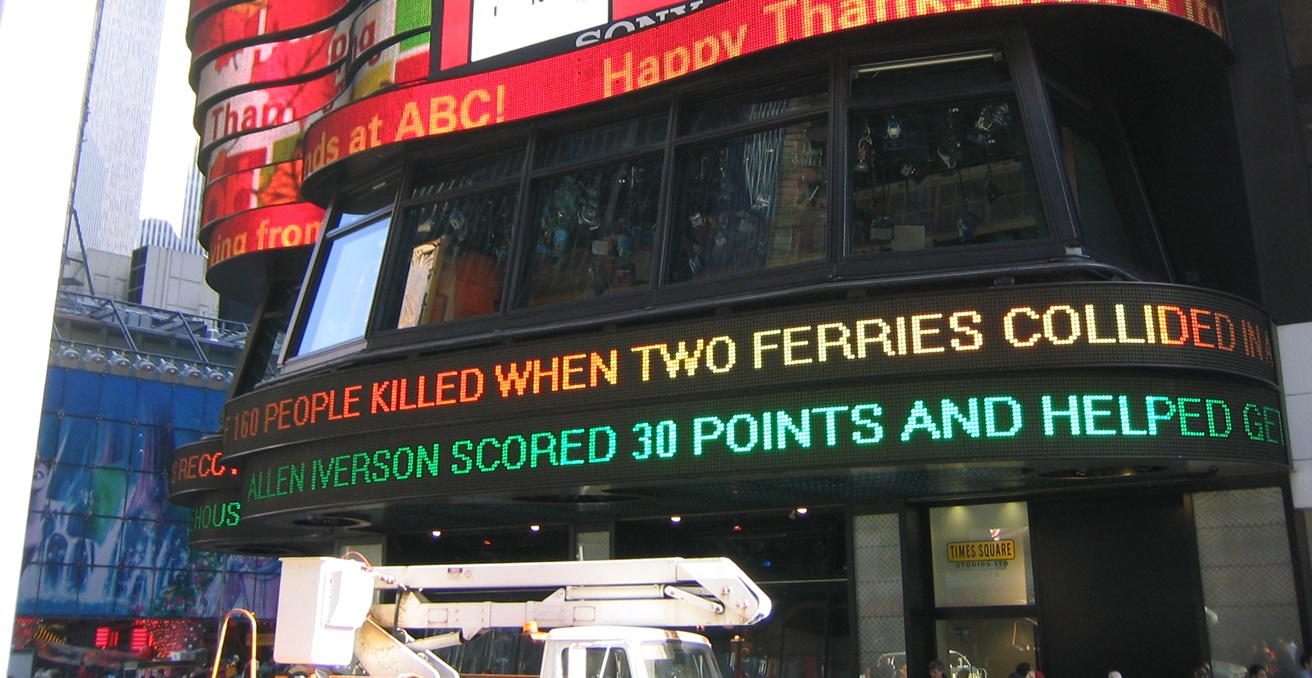

Across the region, from sub-continental India to Australia and micro-states of the Pacific, communities are awash with what Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) chairman, Kim Williams, describes as a tsunami of disinformation and misinformation. “Surging through the streets,” it presents an era-defining challenge for media enterprises purporting to serve the public interest; those whose mission it is to frame narratives around facts and reason, not to exploit the vulnerable or ferment communal and political divisions for narrowly partisan advantage.

It is a challenge of regional security as much as for the social wellbeing of nations and the business models of public interest media. That is why the advocacy group, Australia Asia Pacific Media Initiative (AAPMI), has proposed that the re-elected Australian government should commission a Green Paper to help inform an expanded cross-portfolio response. AAPMI is a non-partisan public interest organisation with high-level media, public policy, diplomacy and Indo-Pacific area expertise.

In the era of massive chatbot assaults and ever more sophisticated AI-powered tools, images and other representations need not even be “real” to be persuasive or manipulative. Increasingly, reliance on human fact-checking to debunk false narratives can be like taking a hand pump to a dam burst. Likely as not, the corrective messaging of mainstream media will not reach or engage many of those most susceptible to the misinformation and manipulation that stokes distrust and discord. The sources of falsehood and abuse can be domestic and communal as much as authoritarian state actors or oligarchs. They all pose hazards requiring effective information interventions.

In Papua New Guinea (PNG), for example, the UN Resident Coordinator cited an incident in which a Highlands schoolteacher died of a massive heart attack while at work. Ill-educated and in search of an explanation for sudden death, local people accused three female maintenance workers at the school of using sorcery. The women were tortured in front of the community and, to compound the atrocity, imagery of it spread throughout PNG via social media. So-called fake news about politics, health, religion, and social issues in PNG are reported also to have caused alarm and panic.

Controversially, in March 2025, the PNG government employed anti-terrorism laws to shut down Facebook for a day; ostensibly it was a “test” in mitigating the spread of hate speech, misinformation, child exploitation, and pornography. This clumsy intervention signified the deep concern of authorities about the material and moral harm being caused; it also spotlit the risks associated with heavy-handed interventions and the potential for abuses of power.

Much like Clive Palmer’s generously-funded but unsuccessful Australian political party, “Trumpet of Patriots,” even a substantial budget and a blitzing campaign of forceful representations do not guarantee the intended results for an advocate or propagandist. The effect of campaigning—and of propaganda—is circumstantial. Those more likely to accept partisan narratives and disinformation are also those less likely to use fact-checking resources. Those who depend for their news on Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok are the most likely to rate disinformation as true.

A recent study of 80,000 people across 40 countries identified four groups likely to favor partisan rather than “impartial” news. In addition to those with ideological motivations, these groups tended to have less power and privilege in the countries surveyed. They were young people, especially those relying on social media for news; women; and the less wealthy and less well-educated. Another study across 19 countries concluded that people holding a conspiratorial view of the world were more likely to accept false narratives. Unsurprisingly, conspiratorial thinking tended to be more prevalent in societies with weak institutions and/or exhibiting low levels of trust in institutions.

It follows that conventional print and broadcast outlets, along with media fact-checkers, are less likely to reach the people most vulnerable to conspiracy theories and cognitive manipulation in the fragmented context of social media and influencer channels. This is a problem both in relation to civic discourse within jurisdictions and for democratic states seeking to inform and influence foreign publics and key individuals. It is a problem compounded by psychological tendencies intrinsic to the human condition.

Like gossip, misinformation travels fast and entertains. Many people enjoy the fun of “hot” disinformation and fake news, while finding “cold” information to be more tedious and pedestrian. They tend to believe one narrative over another because they wish to believe it. Regardless of whether disinformation is partially true or wholly false, it tends to affirm an existing perspective through confirmation bias. Consequently, for people who choose one set of facts over another, the principle of objective truth may have no intrinsic value; rather, a statement’s claim to truth is achieved through the telling of a story that achieves an emotional connection with the target audience. That connection may serve only to heighten distrust or anger directed at “the other” and alienation.

How then should the agents of democracy perform in the international marketplace of ideas when conventionally published facts and reason are not enough? When hostile state or non-state actors choose to “flood the zone with shit,” in the words of MAGA-zealot Steve Bannon? Common and necessary responses in a democratic system include appropriate government regulation, media literacy initiatives, fact-checking, and support for free and accountable media (especially in developing Indo-Pacific economies and/or where institutional guardrails remain under-developed).

The ABC under Kim Williams continues to do well-designed and valuable work with international partners, especially in PNG and the Pacific, under the Australian government’s Indo-Pacific Broadcasting Strategy. But, as fast-advancing technology applications sweep the region with weaponised information, we need to pay more attention to the psychology, tools, and practices required for effective cross-cultural communication and counterpropaganda. As before, the overriding aim is to reach and establish an emotional connection with target audiences; to influence what they think about and how they think about relevant matters, whether geopolitics or the explanation of sudden death by heart failure.

That calls for a wider investment focus than one concentrated on long-established editorial conventions of the newsroom or production suite; one that aims to equip and involve those actors most able to reach deep into communities. For example, it makes sense to apply comparable AI-powered tools to pre-empt or counter the “tsunami” of chatbots, deepfakes, and varied manifestations of information warfare. But it should be acknowledged that these AI tools are “cultural technologies” trained with documents that are framed by cultural and political biases. Systems that may serve in North America or Europe are reported to underperform outside the developed West and in small jurisdictions or where minority languages are in use.

Instead, Australia might look to invest substantially in generative AI-powered technology and the operation of a verification system designed for the communities of Oceania: to identify and contextualise suspicious content; reflect the region’s cultural and linguistic diversity; and engage local media and religious/civil society users to pre-empt or minimise community harms. Potentially authorised users could both act as community moderators and advisers to the AI system’s learning process. The organising principles and (independent) governance model of such a venture would require careful consideration in the interests of regional adoption, credibility, and trust-building. And so too the required level of initial and ongoing investment, likely to be in the millions for even a pilot or small-scale multilingual endeavor, is required.

Australia’s reputational security and the stability of nations throughout Oceania call for significant and non-traditional instruments in what might become the forever campaign against information dystopia.

Dr Geoff Heriot is a consultant on media and governance, a former corporate and editorial executive of the ABC, and author of, International Broadcasting and its Contested Role in Australian Statecraft: Middle Power, Smart Power (Anthem Press). Disclosure: he is a member of the AAPMI steering committee and has undertaken advisory assignments with the ABC’s International Development unit.