What Sort of Space “Race” Should We Be Pursuing?

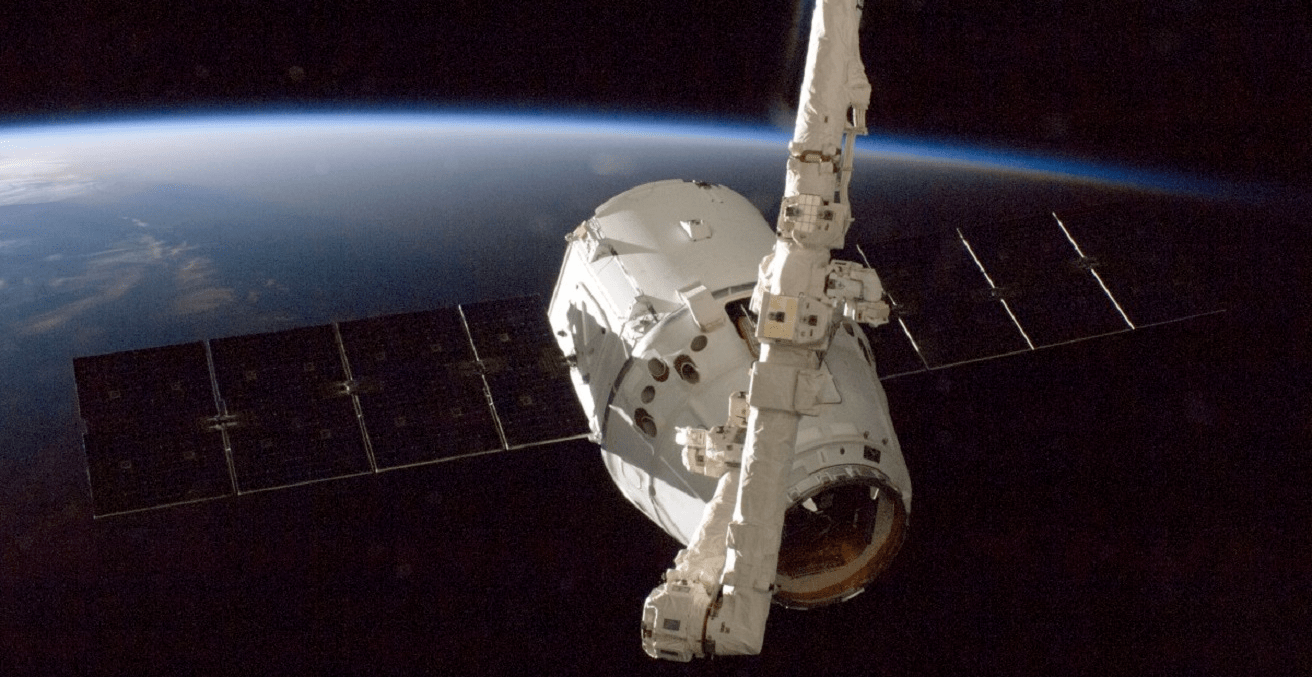

If a war in space does take place, the devastation would be long-lasting and perhaps irreversible. We must work towards civil and commercial activities that enhance capabilities and promote peace in space.

Since the first “Space Race” in 1957, space-related technologies have transformed our lives. Space impacts everyone and has revolutionised communications, medicine, navigation, finance, agriculture, and computing. Space is an important element of critical infrastructure to support the world economy, international trade and investment, strategic thinking, military strategy, national security, science, and the future of humankind.

Yet, despite our remarkable technological progress in space, we are still in our relative infancy regarding what is “possible” – but each advance brings its challenges. If we maintain a “business as usual” approach to the way we conduct space activities, the threats arising from the increasing proliferation of orbital debris loom ever larger. A “day without space” would be disastrous for livelihoods and economies around the world.

Space is complex, multifaceted, and ubiquitous – and our off-Earth adventures thus far have galvanised a series of space “races,” each reflecting the way these interactions have shaped, and are shaped by, a combination of technology, geopolitics, economics, science, law, and culture.

A “Strategic Space Race”

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 in 1957, it represented humanity’s first significant foray into the cosmos. Our imagination was opened to the wonder of space for human endeavour, as science fiction suddenly became science fact. Notwithstanding the possibilities that this pivotal achievement created for humanity, the development of space-related technology at that time was inextricably linked to perceptions of military strength and strategic advantage.

The first Space Race that followed from the Sputnik I mission was characterised by competition between the Soviet Union and the US. It emerged at the height of the Cold War, when both countries sought to flex their respective strategic “muscles.” The prevailing geopolitical mentality contributed to suspicion and fear about what it meant to be in space, which was viewed as an area where the imperative was to be “first and strongest.” In 1960, John F. Kennedy stated that, “if the Soviets control space they can control the earth, as in past centuries the nation that controlled the seas dominated the continents.” He emphasised that, “we cannot run second in this vital race. To ensure peace and freedom, we must be first.” This mutual distrust set in motion a further aspect of the “race” in space, which continues as a threatening presence today.

An “Arms Race in Space”

The desire to counter the space ambitions of others and achieve superiority in space seems to have recently re-emerged. In 2021, the International Committee of the Red Cross warned the international community that, “the human cost of using weapons in outer space that could disrupt, damage, destroy or disable civilian or dual-use space objects is likely to be significant.”

Every year since the early 1980s, the United Nations General Assembly has passed a resolution urging the prevention of an arms race in outer space (PAROS). In October 2021, and again earlier this month, the international community expressed its concern on this matter and urged all United Nations member states “to contribute actively to the goal of preventing an arms race in outer space as an essential condition for the promotion of international cooperation in the exploration and use of outer space for peaceful purposes.”

This comes at a particularly challenging time in geopolitics, where the initial bipolar space “superpower” paradigm has become more complex and multipolar, and an increasing number of countries have or aspire to significant military space capabilities. Some military strategists now suggest that the competitive and congested nature of space will lead to an outbreak of conflict in outer space. Indeed, as tensions on Earth increase, the risk grows that humanity may somehow lurch into a space war, destroying economies and critical civilian and military infrastructure.

Added to this is the alarming build-up of counter-space capabilities worldwide – and the willingness of major space powers to “test” them – as was highlighted once again just last month. We find ourselves hurtling on a downward spiral towards the unimaginable. If a war in space does take place, the devastation would be long-lasting, and perhaps irreversible.

A “Commercial Space Race”

Space is now also playing an important “private” role. The early 1990s marked the beginning of a rapid expansion of the commercialisation of space. Since 1998, the value of the commercial space sector has exceeded the government space sector. The global commercial space economy in 2020 totalled approximately US$400 billion – representing an annualised growth rate of approximately seven percent since 2005 – and is anticipated to grow to between $1 trillion and $3 trillion by 2040.

The commercialisation of space is significant, and the growing number of private space actors will crave “enabling” rules of space that would allow them to expand their business opportunities with strong government support but minimal government interference. These commercial space companies also require a safe and stable environment in which to operate if they are to reap the economic benefits from space that are – potentially – on offer. They will only survive and prosper, along the way developing technology that will provide both public and private benefits, if the characteristics of the race to space are significantly altered.

A “Peace Race in Space”

In 1967, a decade after Sputnik 1, diplomats came together to conclude the Outer Space Treaty (OST). Today, 111 countries have agreed to be bound to this phenomenal feat of international diplomacy as the central platform for their space activities. The OST underlines the common interest of all humanity to explore and use outer space “for peaceful purposes.” It also affirms that space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is free to be explored and used by all countries “on a basis of equality and in accordance with international law.”

The OST also codified the fundamental principles of law for enhancing our common interest in space to thwart potential colonisation ambitions. By declaring that outer space “is not subject to national appropriation” by any means, it established a foundational governance system based on mutual understanding and friendly relations.

Indeed, despite contrary assertions, a space war is not inevitable. A claim that space is the new “warfighting domain” contradicts the six-decade-long understanding that it is a shared area governed by international law, where global interests converge to ensure its exploration and use for the benefit of humanity. The goal of PAROS is vital and must be continued, yet it still contemplates and may even legitimise increased military uses of space. We need to set our ambitions even higher – a pursuit of a “peace race” in space. Paying due regard to the humanity of space and the preservation of its safety, stability, and sustainability leads to no other conclusion.

The OST and multilateral dialogue at the UN have provided the anchor to keep space free from conflict. There is no reason why this overarching legal and institutional framework for peace cannot continue to underpin our attempts to avoid irresponsible behaviour in space. The recent diplomatic moves in the UN towards reducing space threats through norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviours is a vital step along this path, augmenting the objective rationale and fundamental basis of the international legal framework.

Adherence to fundamental principles that promote peaceful uses of space is essential if we are to avoid a “tragedy of the commons” in space. A focus on a “peace race” in space will enhance a deeper understanding of the common interests of all to act responsibly, thus allowing for further benefits to be utilised by every element of the global community.

It is therefore important to focus on the race ahead. We need to recalibrate the language of space, and our underlying thinking about the regulation of space, away from the rhetoric of conflict, strategic competition, and even warfare towards civil and commercial activities that enhance capabilities and promote the peaceful uses of space.

The complex range of vested interests in space mean that changing entrenched perspectives is never easy. Yet, we have no other practical choice. In an era when humanity is faced with climate change, a pandemic, and the rapid exhaustion of resources, the common interests in this peace race are even more important, both on Earth and in outer space.

Steven Freeland is an Emeritus Professor at the University of Western Sydney, a Professorial Fellow at Bond University, and the Director of the International Institute of Space Law.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.