Vietnam’s foreign policy has entered a new phase under the leadership of General Secretary To Lam, who has framed the coming decades as the “era of national rise” (kỷ nguyên vươn mình của dân tộc). This vision seeks to transition Vietnam into a high-income, influential middle power by 2045, the centenary of the modern Vietnamese state.

Public diplomacy, with its key instrument of cultural diplomacy, has long been part of Vietnam’s international engagement, serving to project a distinct Vietnamese identity globally while reinforcing internal legitimacy and social cohesion. In the context of the national rise agenda, cultural diplomacy is now being given a stronger presence and broader objectives. It is becoming a core battleground of influence, and a key pillar of Vietnam’s comprehensive diplomacy alongside political and economic engagement.

The 2021 Strategy for Cultural Diplomacy to 2030 builds on earlier efforts, including the 2009 designation as the Year of Cultural Diplomacy and the first national strategy in 2011. While it reflects a longer policy trajectory, the 2021 strategy also matches the urgency of the national rise agenda and, for the first time, explicitly incorporates the concept of public diplomacy. No longer an add-on to foreign policy, culture is used to build trust, deepen international partnerships, enhance national soft power, and facilitate socio-economic development.

Vietnam has already surpassed some of its cultural diplomacy targets. As of 2024, it had secured 67 UNESCO-recognised cultural and natural heritage elements, well beyond its initial goal of 60 by 2030. Cultural events abroad, such as the annual “Vietnam Days Abroad,” are increasingly coordinated with trade, tourism, and investment initiatives. Language diplomacy is gaining traction too, with several universities in Italy and France integrating Vietnamese into their curricula.

In the first quarter of 2025, the country welcomed over six million foreign visitors, a record high that highlights its growing international appeal. From heritage diplomacy in UNESCO to regional initiatives within ASEAN, these achievements suggest a more integrated approach that aligns cultural initiatives with broader economic and strategic priorities.

As I noted in a 2022 book, Vietnam’s cultural diplomacy operates not just as an external projection of soft power, but also as a domestic tool to reinforce national identity and regime legitimacy. In this hybrid model, the boundaries between public diplomacy, cultural governance, and political communication are mutually reinforcing. Just like public diplomacy.

Once confined to top-down, state-centric messaging, public and cultural diplomacy have gradually embraced a broader, more flexible toolkit. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs coordinates a wide network of state and non-state participants, implementing a whole-of-nation approach. This reflects both the state’s ambition and need for broader legitimacy and control, especially in an era shaped by digital platforms and decentralised storytelling.

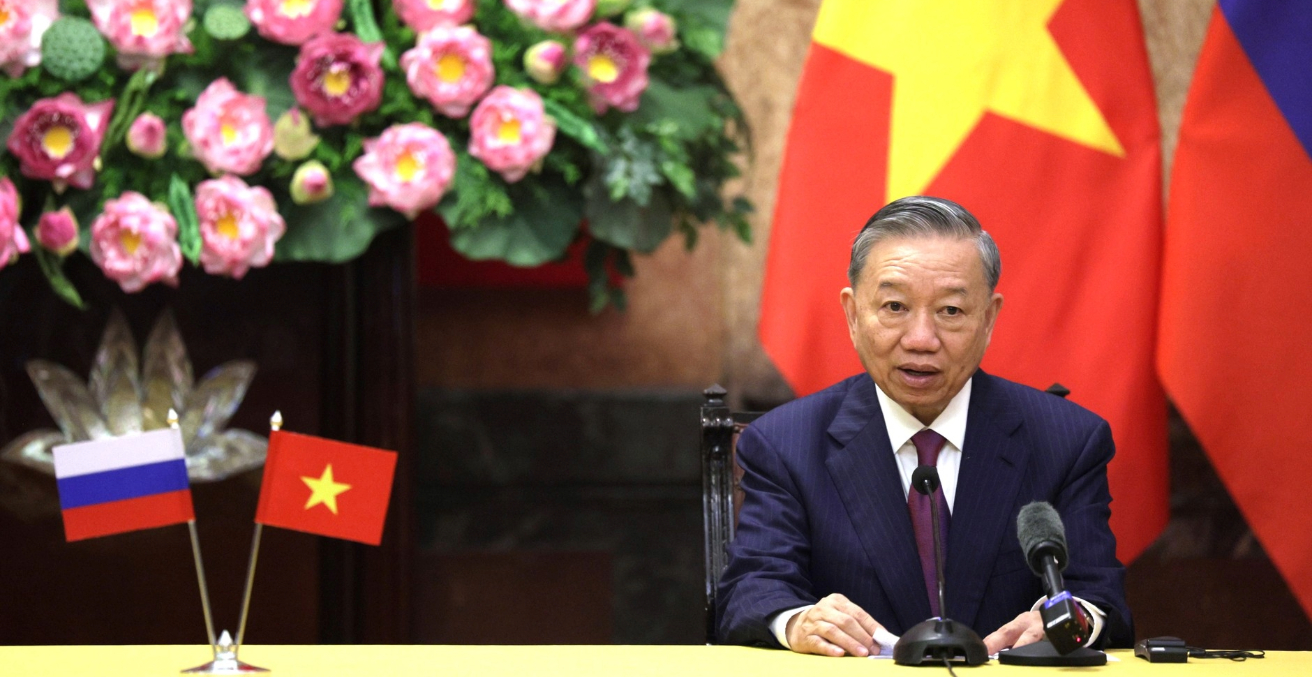

To Lam has defined 2025–2030 as a “decisive sprint” toward modernisation, having spearheaded the most consequential institutional recalibration in decades. Cultural diplomacy is poised to serve both external engagement and internal cohesion, by reinforcing a unified cultural identity at home and abroad.

In a late 2024 meeting with artists, To Lam called culture “a special product of people and nations” and stressed that cultural development must support social progress and state functionality. For him, culture-based soft power is not just complementary to economic or military capabilities—it is essential to the nation’s rise.

Part of the appeal lies in culture’s political safety. In a system where political dissent is tightly managed, culture offers a relatively uncontroversial space to project identity and values, without triggering sensitive debates on rights or governance. For international partners, this creates opportunities for engagement through cultural exchange and diaspora collaboration, without crossing political red lines.

In that light, cultural diplomacy serves To Lam’s vision in several ways. First, cultural diplomacy contributes to a stable foreign environment. Cultural exchanges are often built into state visits, helping to create goodwill amid strategic differences.

Second, it helps craft Vietnam’s image as a confident, principled nation. UNESCO recognitions and other international honours are used to tell a story of a country that is rising not through coercion but through creativity and heritage.

Third, cultural diplomacy supports internal cohesion. Pride in cultural heritage is used to rally public support for the broader national project. Cultural events and accolades are widely covered in state media, reinforcing a narrative of global esteem and national pride.

These cultural milestones, when presented through state-aligned platforms, strengthen regime legitimacy and broaden To Lam’s appeal. With his deep background in public security, Lam’s promotion of soft power adds a more humanistic and internationally attuned dimension.

Yet this model comes with contradictions. The most prominent tension lies between narrative control and the need for authenticity. Cultural content remains tightly regulated. Despite efforts to promote innovation, sectors like film, literature, and contemporary art are still subject to ideological scrutiny.

State agencies such as the Central Film Appraisal Council routinely censor works deemed politically sensitive or morally inappropriate. This restricts the scope for creative experimentation and limits Vietnam’s ability to project authenticity in a competitive global soft power landscape where influence increasingly depends on cultural openness and narrative complexity.

A similar tension is visible in how Vietnam represents its cultural diversity. Effective cultural diplomacy draws strength from the country’s ethnic minority traditions, regional customs, and varied historical legacies. Yet official messaging tends to promote a singular, unified national identity anchored in Party-sanctioned narratives and cultural values. Ethnic and regional traditions are often presented in aesthetic or folkloric terms, rather than as integral to the national story. Without greater narrative flexibility, Vietnam risks underutilising one of its most valuable assets: the complexity of its cultural fabric.

Diaspora engagement reflects a related challenge. Younger overseas Vietnamese are increasingly participating in cultural programs and digital initiatives, celebrating Vietnam’s recent achievements. However, older generations with historical grievances remain sceptical of state-led efforts.

Although the government frequently invokes “national harmony” (hoà hợp dân tộc), it has offered little in the way of formal reconciliation or acknowledgement of contested historical experiences. As a result, engagement efforts sometimes provoke protest or remain surface-level, especially when they avoid politically sensitive themes.

This is a missed opportunity. Overseas Vietnamese contribute significantly to the economy—sending over US$16 billion in remittances in 2024—and play significant roles in entrepreneurship, investment, and knowledge exchange. That’s why unless supported by more inclusive dialogue and plural representation, such engagement risks being seen as transactional rather than transformative.

Looking forward, Vietnam’s public and cultural diplomacy would benefit from deeper localisation and diversification. Localities with distinct heritage and creative capacity could be empowered to lead their own international cultural campaigns, backed by the central government.

Additionally, Vietnam should do more to amplify its nation branding on social media via strategic partnerships with tech firms, creators, and platforms. At the same time, Vietnam’s international cultural engagement should build on its own foundations, such as traditional arts, national storytelling, and its overseas communities, rather than adopting foreign models unfit for context.

Ultimately, cultural diplomacy is not just about showcasing tradition or increasing tourist arrivals. It is a strategic instrument through which Vietnam negotiates its place in the world—and persuades both its citizens and foreign partners to buy into that trajectory. In the era of national rise, Vietnam’s influence will depend not only on what it achieves but also on how convincingly it tells its story.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect those of his workplace and affiliated institutions.

Dr Vu Lam a political scientist affiliated with UNSW Canberra, focusing on Southeast Asian trade, diplomacy and strategic affairs. He has worked across research, policy and government sectors, and writes regularly on regional integration and Australia’s Indo-Pacific engagement.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.