President Xi Jinping’s massive Victory Day parade on September 3rd wasn’t just about commemorating history—it was China’s boldest display of military power in years, featuring Putin and Kim Jong Un as honoured guests while unveiling “satellite hunter” missiles and autonomous warfare systems that signal a new era of great-power competition. With Western allies boycotting and tensions soaring, this carefully choreographed spectacle revealed as much about China’s strategic anxieties as its growing capabilities.

Introduction

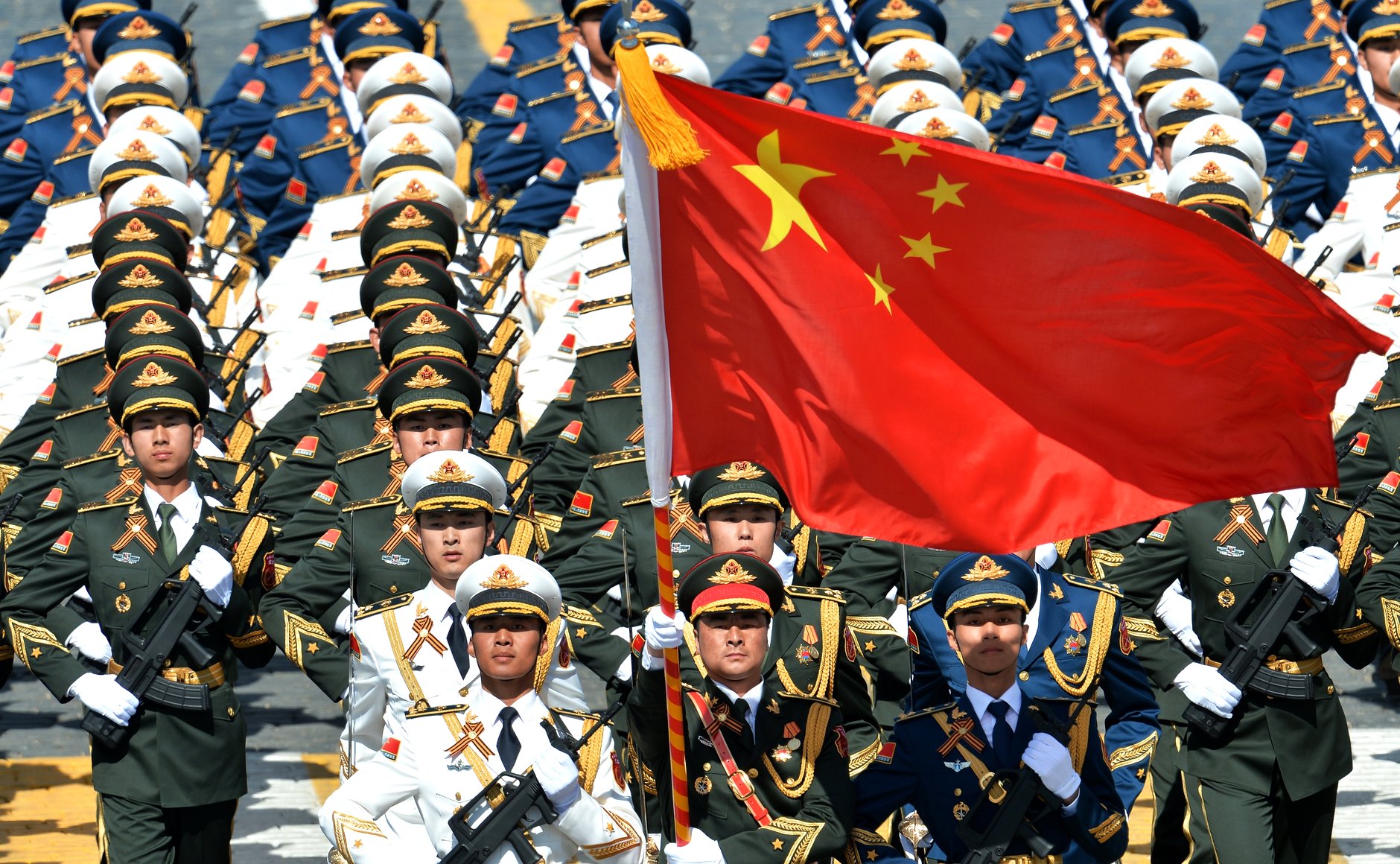

On 3 September 2025, Beijing staged its most significant military parade in six years to mark the 80th anniversary of victory over Imperial Japan and the end of the Second World War. This Victory Day parade was far more than ceremonial—it was President Xi Jinping’s most comprehensive showcase of China’s military modernisation, diplomatic alignment, narrative influence, and great‑power ambition.

Breaking from the traditional cycle of decade-year National Day parades, this was Xi’s fourth large-scale military review (following those in 2015, 2018, and 2019) and considered the largest in the Party’s history. The decision signalled both political intent and strategic defiance, making the occasion as consequential as the hardware it displayed.

The timing was pivotal. On the international stage, it coincided with fractures in U.S. alliances, renewed tensions between Washington and Moscow, and tightening strategic coordination among China, Russia, and North Korea. Domestically, it came amid economic slowdown and a sweeping purge of military leaders—dislodging two defence ministers and nearly half of the Central Military Commission—while recent South China Sea naval incidents had fuelled doubts about the PLA’s performance. The parade was as much a bid to restore confidence and project deterrence as it was to commemorate history.

The Politics: allies, partners and absentees

Allies close to the podium—Putin and Kim Jong Un—stood alongside Xi, emphasising Moscow and Pyongyang’s centrality to Beijing’s security calculus. Their joint appearance was a stark collective defiance against Western criticism and sanctions. Kim’s first visit to China since 2019 signalled a revitalised Sino–North Korean alignment. It marked the first participation of a North Korean leader in a Chinese military parade since his grandfather Kim Il-sung attended in 1959.

Beyond its closest partners, China also courted leaders from 26 countries, including Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia, Iran, Belarus and Pakistan. It underscores China’s self-proclaimed “friend circle”. It also echoes Xi’s recent proposal of “Global Governance Initiative” with a pointed emphasis on a mindset of mutual benefit, rather than the Western-led logic of Cold War rivalry and confrontation.

Their presence contrasted sharply with the absence of Western powers, most of whom boycotted the event — partly in protest at Putin’s attendance and his International Criminal Court warrant.

Adding a semi-official layer, Beijing invited former politicians such as Japan’s Yukio Hatoyama, Australia’s Bob Carr and Dan Andrews, and Taiwan’s Hung Hsiu-chu. Most of them came under pressure from domestic politics due to the intensifying geopolitical confrontations. Caught between domestic criticism and international influence, these “international friends” function as semi-official conduits of influence, bridging China and the West during this critical and sensitive moment.

The Strength: weapons, strategy and signals

This Victory Day parade was a carefully staged demonstration of the PLA’s transition towards integrated, multi-domain operations. Four new and critical aspects deserve our attention.

Coordinated multi-domain/multi-forces operations

For the first time, the four forces—the Aerospace Force, the Cyberspace Force, the Information Support Force, and the Joint Logistics Support Force—marched as independent entities alongside the traditional services of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force. Their appearance underscored Xi’s vision of future warfare, in which victory depends on cyber dominance, information intervention, and seamless coordination across multiple domains.

The weapons reinforced this structural reorganisation unveiled, which illustrated how the PLA is moving beyond traditional firepower contests towards what Chinese strategists describe as “information weaponisation”. In this conception, success lies in controlling reconnaissance, communications, and strike corridors to neutralise an opponent’s ability to respond. The principle of “informationisation” and “intelligentisation” ran through the entire weapons display.

Strategic deterrence: longer, heavier and faster

The PLA’s strategic missiles, long billed as the “great power assets” of China’s parades, were once again the centrepiece. Beyond the familiar YJ hypersonic anti-ship missile, DongFeng and Julang Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), and Hongqi air-defence interceptors, two developments stood out.

First, China highlighted its ability to extend deterrence into near space. The HQ-29 missile defence system, unveiled for the first time, was described as a “satellite hunter”, capable of intercepting ballistic missiles and low-orbit satellites at altitudes of up to 500 kilometres. Alongside it, the JL-1, JL-3, DF-31, and DF-61 missiles illustrated the maturation of China’s land-, sea-, and air-based nuclear forces.

Second, the parade revealed advances in missile speed and payload. The JL-3 and DF-31BJ missles, both new entrants, signalled diversification of delivery systems. Even more striking was the debut of the DF-5C, the new liquid-fuelled ICBM with global strike capability, and the cutting-edge DF-61 that has been seen as among the world’s most advanced ICBMs for its velocity, range, accuracy and warhead capacity.

Autonomous and electronic systems

The parade devoted particular attention to autonomous systems. Large autonomous underwater vehicles such as the AJX002 were rolled out to showcase China’s capacity for long-range patrol, mine clearance, and undersea surveillance.

In the skies, the FH-97, a new stealth drone with tailless design, was presented as “loyal wingmen” for the J-20 stealth fighter, the only two-seat 5th-generation fighter. Meanwhile, an autonomous helicopter drone was predicted to support Z-20T’s future operations. On land, smaller crewless ground vehicles, machine-dog platforms, the autonomous turrets on China’s new 4th-gen tanks and the new QBZ-191 rifle equipped with electronic modules demonstrated the PLA’s determination to integrate robotics and autonomy across all domains.

Echoing Xi’s emphasis on electronic and hybrid warfare, the systematic command systems were embodied by large-sized air platforms, including the KJ-600 carrier-based airborne early-warning aircraft, the Y-9 electronic warfare platform, and formations of J-16D and J-35A fighters configured for jamming and suppression of enemy air defences. Together, these platforms indicated that the PLA is investing heavily in the capacity to operate in and dominate complex information environments.

Quicker innovation

These displays broadcast a message about quicker innovation cycles. Whereas earlier generations of Chinese weaponry followed roughly three-decade development spans, the transition from third to fourth-generation systems has been compressed into just 15 years.

Narrative: history, memory, legitimacy

Internationally, the Victory Day parade positioned the CCP as the central victor in World War II, thereby denying rival historical narratives. Xi’s directive to “tell the story of the War well” was meant to reinforce CCP legitimacy and recast contemporary tensions as continuations of past struggles. For a long time, the CCP has been criticised both for its limited participation in, and for its self-aggrandised claims of contribution to, the World Anti-Fascist War. In his parade address, Xi struck a harsh tone, stressing the CCP’s determination to confront hostile and ‘evil’ forces without fear.

Domestically, the parade served to restore trust and rally public confidence amid economic and military turbulence, as seen on social media. Xi ended the parade by warmly greeting veterans of the War, many nearing a century in age and formerly soldiers of the KMT. Their attendance is a signal to the Taiwanese government, which is seen as a separatist from a unified China and holds a “special relationship” with Japan. To the international observers, it communicated a clear deterrent message: China is self-reliant, capable and resolute.

Dr. Guangyi Pan is a Lecturer in International Political Studies at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, UNSW Canberra. His research focuses on asymmetric politics, China’s alignment policies, and realism of International Relations. He has published two books and several articles in leading journals, including International Affairs, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, Pacific Review, The Chinese Journal of International Politics, and The Chinese Journal of Political Science. He received his PhD in International Politics from UNSW Sydney in 2024. Previously, he studied at Nanjing University and worked at UNICEF China.

This article is published under Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.