A new survey of more than 850 businesses active in the Australia–China economic corridor reveals sustained confidence in China’s economic potential, despite shifting global dynamics. While the Australian government continues to encourage trade with China, it walks a finer line when it comes to investment.

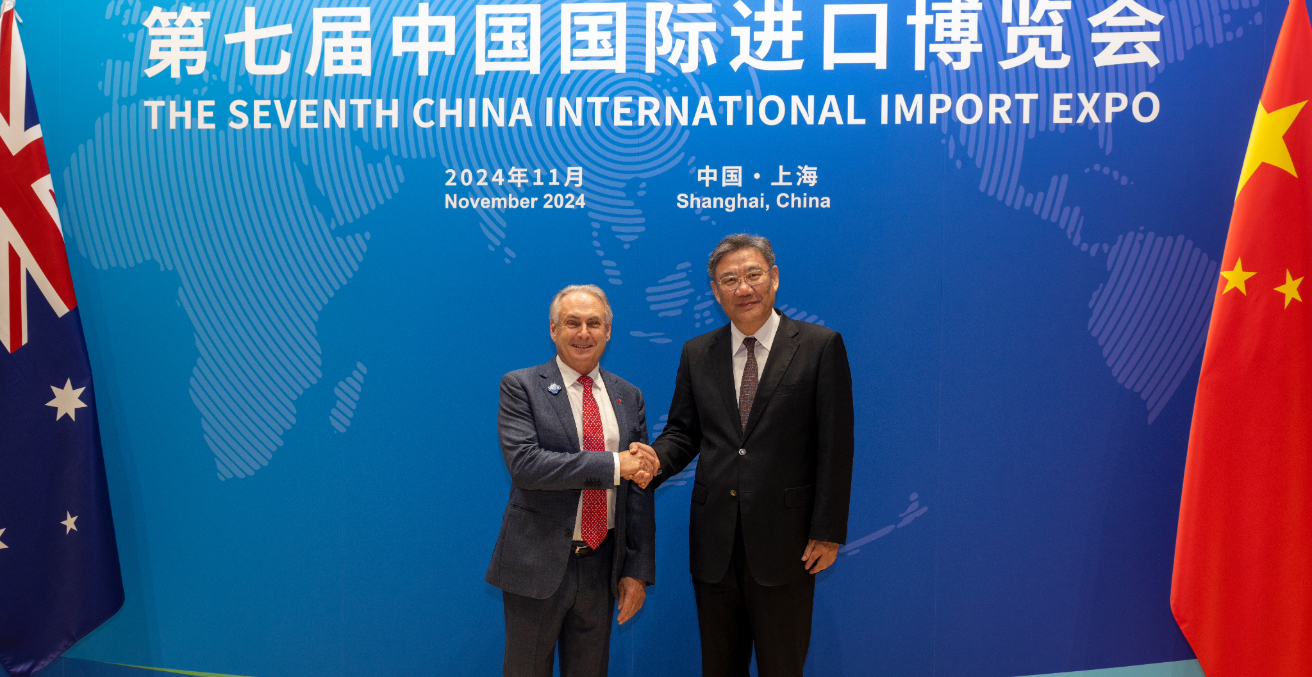

Trade Minister Don Farrell doesn’t buy post-pandemic talk that China’s economy has “peaked” or become “uninvestible.” He also rejects the idea that a geopolitical divide between Canberra and Washington on the one hand and Beijing on the other means that Australia’s strong economic ties with China are unsustainable.

Beginning his second term in the role, Farrell says, “We don’t want to do less business with China, we want to do more business with China,” adding that Australia’s interests will determine the Albanese government’s choices, not “what the Americans may or may not want.” A report that was released in Beijing on 5 June finds Farrell’s stance is backed by hundreds of the best informed and most deeply engaged businesses in the Australia-China corridor.

Two big themes stand out in the China-Australia Chamber of Commerce’s (AustCham China) latest Doing Business in China survey, produced with the support of the Australia-China Business Council (ACBC) and the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS:ACRI).

The first is positivity and commitment to the China market. Just four percent of respondents said they had recorded a loss over the past year, down from nearly one-fifth in 2023, while the proportion reporting an increase in profits was double that reporting a decrease.

And on the two-year outlook, those optimistic about the market opportunities outnumbered the pessimists by a ratio of more than two to one. More than two-thirds rank China among their top three global investment priorities in the coming three years.

A caveat is that AustCham’s survey finished in the field before the second Trump administration ramped up its trade war that had China as a focus. But the Australia-China and China-US economic relationships have long run on different tracks.

Whereas China’s economy has become more competitive with America’s, Australia’s remains highly complementary. Since the first Trump administration, both Coalition and Labor governments have also been critical of the US for unilaterally imposing tariffs and other barriers targeting China in defiance of World Trade Organization rules.

The potential fallout from geopolitical tensions with the US also needs to be kept in perspective. The future of China’s US$19 trillion-dollar economy, which in the first quarter grew another 5.4 percent year-on-year, is fundamentally a much bigger story.

Upon returning from a recent visit, Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia Andrew Hauser remarked that what most struck him about a roundtable discussion with Australian companies in Shanghai “was how upbeat most, if not all, of the firms were about the outlook of their businesses.” Hauser said the bank’s own forecasts shared a “relatively upbeat view” that China’s growth this year would be “a shade under five [percent]” and remain “still pretty strong” in 2026.

The second big theme in AustCham’s survey is that what Canberra says and does matters. In a vote of confidence for the Albanese government’s diplomacy, more than half of respondents reported that doing business in China had become easier following the improvement in bilateral relations since 2022. Just seven percent were pessimistic about the outlook.

But when it came to foreign investment settings, the assessment was scathing. Among 530 respondents, not a single Chinese-owned company and just two Australian/other foreign-owned ones said these settings were conducive towards investment from China.

Australian/other foreign-owned companies were even more confused than Chinese ones with an extraordinary 93 percent contending that the Foreign Investment Review Board’s (FIRB) guidelines and requirements for obtaining approval were unclear or very unclear. With FIRB’s job being to coordinate across government agencies and formulate a recommendation for the Treasurer, ultimately this is a message being delivered to Jim Chalmers as the final decision-maker and minister who determines foreign investment approvals processes.

More than just a negative business “vibe,” the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported earlier this month that the stock of Chinese investment in Australia had fallen by 20 percent since 2021 and now stands at just one percent of the total. In comparison, the US and UK shares are 27 percent and 17 percent, respectively.

The problem is not simply a matter of dollars. Foreign investment often brings with it advanced technology, talent, and access to rapidly evolving supply chains. And these days, more and more Chinese companies are the global leaders in their industry. In other words, sometimes an American or Japanese investor is a poor substitute for a Chinese one.

Failing to engage doesn’t just mean lost opportunities—it means falling behind: with higher input costs, slower innovation, and a diminished role in shaping the industries that will define the next era, like clean energy, critical minerals, and advanced manufacturing.

Australia’s economic transformation will not succeed by turning inward. It will succeed by engaging strategically—learning from the world’s most dynamic economies, including China, and building partnerships that align with our national interests, economic priorities, and values.

Professor James Laurenceson is the Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS:ACRI).

Vaughn Barber is the Chair of the China-Australia Chamber of Commerce (AustCham China).

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.