Rethinking Australia's Pacific Islander Migration Policies

Australia’s approach to Pacific migration needs to refocus as climate change worsens. Going forward, Australia should prioritise migrant dignity and mobility.

The announcement that Australia’s refugee arrangement with Papua New Guinea (PNG) would wrap up by the end of 2021 came as welcome news to many. Since 2012, over 4000 individuals seeking asylum in Australia by boat have been subject to offshore processing on the island nation of Nauru and on Manus Island, PNG as part of the Australian government’s contentious Pacific Solution.

Australia has a blotchy track record with asylum. It accepts over 13,750 refugees per year while concurrently maintaining a costly offshore processing program that has been derided as failing in deterring boat arrivals, inadequate in preventing maritime deaths, and barely toeing the line of international rights legality. Although a similar program on Nauru will proceed, the end of the PNG deal is a step closer to shelving the flawed policy.

Indeed, its termination should reignite discussion around Australia’s Pacific focus and migration policies more broadly, and attention needs to shift to include the potential wave of displaced Pacific peoples seeking asylum in surrounding nations.

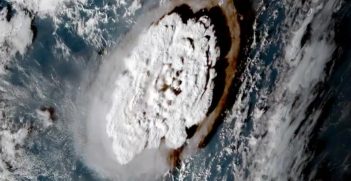

On the innumerable islands of the Pacific Ocean, climate change is magnifying the frequency of natural disasters and multiplying the threats of preexisting stressors on vulnerable communities. The region is beset with overlapping crises: rising sea levels are swallowing habitable land, erosion is denuding the soil of nutrients, fish stocks are dwindling, and potable water is increasingly scarce. These environmental changes are further compounded by seismic activity and ever-more-frequent cyclones, leading to prolonged, widespread post-disaster recovery.

During the pandemic, the islands’ remoteness has mostly spared them of COVID-19 cases, but border closures have ripped out the region’s lucrative tourism sector and similarly put a halt to seasonal worker schemes that sent back crucial remittances.

Aid provided through beneficial sustainable development programs like Australia’s Pacific Step-up help provide the myriad Island nations greater resilience to cope with a changing climate. However, to remedy a limited labour market, disaster-preparedness, and environmental degradation, the Lowy Institute has called for additional multi-year aid funding of at least US$3.5 billion to avoid what has been labelled a potential “lost decade” for the region’s 10+ million inhabitants.

In the face of increasingly dire environmental prospects, the UN estimates that inhabitants in migrant-sending Pacific hotspots like low-lying islands and atolls are set to experience an enormous increase in forced displacement by 2055. The surrounding region needs to be prepared for this upsurge in internal and cross-border displacement.

Crucially, Islanders must not be viewed as victims, so-called “climate refugees.” As chanted by protesters at a recent climate rally: “we’re not drowning, we’re fighting!” Pacific Islanders deserve and desire to remain on their ancestral lands, and community-led action taken to protect land and culture ought to be fostered first.

Many affected communities opt for kin-based relocation rather than international migration. Fiji, for instance, has created guidelines on climate-induced internal island-to-island relocation. Similarly, in highly urbanised Kiribati, overcrowding caused by insufficient high ground for internal relocation led ex-President Anote Tong to buy arable land in Fiji to protect food security, but with the possibility of relocation sites for the i-Kiribati people.

Further, circular migration, undertaken to maximise job and social opportunities, has long been part of Pacific islander culture by allowing individuals to maintain firm links to their homeland. Australia, New Zealand, and the United States sit atop the preferred list of countries for labour migration for Islanders. Australia’s Pacific Labour Mobility and New Zealand’s Pacific Access Scheme have demonstrated win-win gains for workers and employers alike by allowing Islanders to be employed in agriculture and regional areas. But more permanent solutions remain elusive.

For each community, migration is a multi-faceted decision-making process, unjustly hindered by scant visa opportunities for individuals from countries with a high likelihood of sending migrants. Similar legal restrictions also apply to asylum-seekers, as shown in the watershed case of i-Kiribati man Ioane Teitiota, whose asylum claim in New Zealand was rejected due to the existing legal frameworks failing to recognise refugee status as it pertains to climate-induced threats.

If legal migration options remain unobtainable, displaced persons may seek refuge in countries like Australia and New Zealand via irregular means. In this scenario, rehashing a policy of offshore processing will contribute to a humanitarian disaster and a destabilised Pacific. Instead, as championed by the Kaldor Centre, proactive measures to create enhanced mobility would enable willing Islanders to migrate with dignity. By expanding work opportunities and visa pathways to permanent residency, Australia could offer further assistance to expatriate Islander communities and utilise the latent workforce of individuals wishing to learn and upgrade their skills.

Ultimately, climate-related relocation of Pacific Island communities should not be a fait accompli, but rather a last-case option. As the region’s top aid donor and strategic partner, Australia must offer more inclusive, expansive, and lawful methods of longer-term migration to mitigate a looming crisis.

Dominic Simonelli is a postgraduate student of international relations. Dominic has a keen interest in migration and human rights, and has recently completed a period of humanitarian volunteering with asylum-seekers in Greece.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.