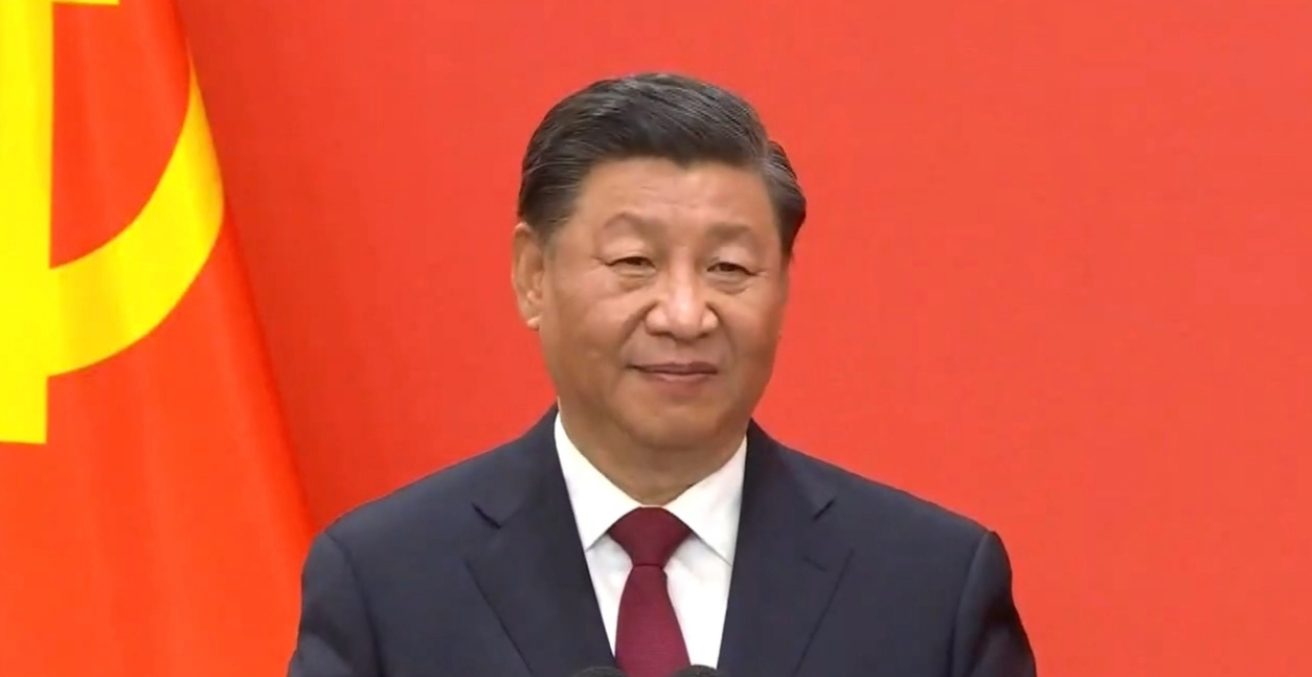

As Xi Jinping tightens his grip on power amid economic headwinds and political uncertainty, questions of succession loom large. The path beyond Xi, marked by purges, rivalries, and competing visions for China’s future, remains shrouded in secrecy but carries global consequences.

In October, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is scheduled to hold its annual plenary session where the Central Committee will meet to determine policy and the country’s general direction, including leadership. In China, the CCP and the leader hold immense, omnipotent power. The single-party state controls its population through SkyNet, a real-time urban surveillance system enforcing compliance; through the Great Firewall and Great Canon, which restrict information, encourage self-censorship, and spread disinformation; and through brutal oppression, particularly in remote regions such as Tibet and Xinjiang. At the top of the Party, the General Secretary imposes a narrative—leadership thought—often expressed as an aphorism.

The leader’s thought guides behaviour and justifies sacrifices made for socialism. Mao Zedong’s anti-imperialist rhetoric and recasting of Marxism-Leninism devolved into a leadership cult, which ultimately resulted in the chaos of disrupted education and the madness of the Cultural Revolution. Subsequently, the Party attempted to limit the power of leaders by setting two-term limits.

As leader, Deng Xiaoping prioritised economic reforms, famously asserting that the colour of a cat—its ideology—was irrelevant, so long as it could catch mice and function effectively in economic terms. While urging caution abroad under his “Hide and Bide” strategy (hide your strength, bide your time, never take the lead), he promoted bravery in domestic reform. His approach, expressed through the Chinese metaphor, “Cross the river by feeling for the stones,” was pragmatic, experimental, and gradualist.

Jiang Zemin added his “Theory of Three Represents” to expand the Party’s base, while Hu Jintao emphasised a “Scientific Outlook for Development,” which aimed to reduce the widening inequalities within China to build a “Harmonious Socialist Society,” thereby lessening the chance for social conflicts to emerge.

Within the leadership pantheon, the most consequential since Mao is Xi Jinping. Now 72 years old, Xi has enshrined his leadership role by removing the two-term limit and embedding his own thought— “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”—into the constitution. Xi’s thought is expansive and multifaceted, earning him the nickname “Chairman-of-Everything.” It is reinforced by the promise of fulfilling the “China Dream” of national rejuvenation: a long-held desire that China would reemerge as the global leader under a Sino-centric world order. Xi also side-stepped Deng’s “hide and bide” strategy, adopting a more assertive and aggressive foreign policy, believing China’s time had arrived.

China’s economy is increasingly unstable, particularly in the property sector. Youth unemployment remains high, the Zero-Covid policy ended in failure, and the country is facing a demographic decline earlier than expected. More significantly, the leadership has retreated from consumption-led growth—a path that poses political risks Xi Jinping appears unwilling to confront. This shift has forced bankrupt provincial governments to sustain both real and superficial growth through the shadow economy and opaque financial instruments that merely circulate debt. These economic pressures are not just technical—they reflect deeper leadership challenges, raising questions about the resilience of Xi’s governance model, the fraying social contract between the Party and the people, and the viability of a fourth term for Xi amid growing internal and external scrutiny.

At some point, China will have a new leader, but the path to that inevitable change is obscured and speculative. While Xi has not appointed a clear successor, discussions of potential replacements typically include Ding Xuexiang, Li Qiang, Cai Qi, Liu Jie, and, more recently, Wang Yang. Wang was Party Secretary of Guangdong and served as a member of the Politburo Standing Committee between 2017 and 2022. At 70 years old, he isn’t a young leader but has a reputation as a liberal reformer.

Succession and the path to leadership in China can be difficult, if not horrific. Liu Shaoqi, who headed the PRC from 1959, was purged in 1968, publicly denounced, and beaten by Mao’s Red Guards before dying alone on a concrete floor. Xi was a member of the sent-down youth, experiencing the hardships of that time, and Deng was purged many times before his final rehabilitation, before becoming leader. Purge and renewal remain a Party tool for self-purification. For example, Bo Xilai was put on trial in 2011 shortly before his rival for power, Xi, took the leadership.

Xi’s decades-long anti-corruption campaigns are widely viewed as purges of his political rivals, allowing him to cement his power. Of the more than 100 recently, Wang Renhua, Secretary of the Central Military Commission, Wang Chunning, Commander of the People’s Armed Police, and Zhang Jianchun, from the Central Propaganda Department, were caught up in Xi’s military purges. However, Xi’s Stalinist approach to purging, targeting allies and appointees alike, now leaves him in a precarious position.

While the CCP leadership succession process has several negative elements, it does enable abrupt change and has built a leadership group with useful skill sets. China altered immensely from Mao to Deng and, subsequently, the world around it. Forty percent of new Politburo members since 2022 have a military-industrial background. These engineering skills and CCP dominance have shaped the Chinese domestic market, leading to global development prowess as the lead supplier of electric cars (70 percent of global production) and solar panels (exceeding 80 percent of global production). In comparison, most Ministers and Cabinet Members in the US and Australia have Law and Arts degrees.

The question of what comes after Xi will have wide ranging implications. Given the trade war with the US, economic de-linking, and domestic turmoil, a Xi successor would attempt to quell and consolidate. The Party may seek short-term stability to consolidate Xi’s gains in the US conflict, awaiting the next US president, and focus on regional influence through soft power initiatives and structural power around the Nine-Dash Line and Taiwan. The new leader might echo the aphorism 固守阵地 (gù shǒu zhèn dì): “hold the fort” or “defend the position” as a basis for policy positions. Wang appears as likely a candidate as any. He holds a master’s in engineering, attended the Central Party School, and isn’t seen as a “rising star” but more of a seasoned politician.

Dr Jonathan Ping is an associate professor in the fields of political economy and international relations at Bond University. His research focus is on middle power statecraft theory, great power statecraft theory and a theory of the nature of hegemony in and from Asia. He is a Director of the East Asia Security Centre. He is the author of: Ping, J.H. (2005). Middle Power Statecraft: Indonesia, Malaysia and the Asia-Pacific (1st ed.). Routledge. Twitter handle: @drjhping.

Dr Anna Hayes is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations at James Cook University and an Honorary Research Fellow at the East Asia Security Centre. Anna has presented numerous papers in Beijing, on topics ranging from the situation in Xinjiang, how the Belt and Road Initiative has been viewed outside of China, as well as the Quad and the Indo-Pacific from the Australian perspective.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.