Indonesia’s August 2025 protests were fueled by deepfake videos and misinformation that resonated with existing economic grievances and anti-elite sentiment, demonstrating how false content can mobilize public anger when it aligns with lived experiences. The tragic death of motorcycle taxi driver Affan Kurniawan under a police vehicle transformed online outrage into street demonstrations, showing how networked polarization can both divide and unite communities around calls for reform.

Indonesia’s late-August 2025 protests demonstrated how misinformation and networked polarisation can fuse to shape online narratives and influence offline choices. A viral deepfake that appeared to show the former Indonesian Finance Minister Sri Mulyani calling teachers “a burden” sparked indignation, which was shared around two weeks before the peak of the protest. Another video showed an old clip of Surya Utama/Uya Kuya, a member of the House of Representatives (DPR), dancing, which was re-uploaded with a misleading caption implying that he mocked the notion that “3 million rupiah per day is small,” falsely tying it to the DPR pay/allowance controversy.

Both have since clarified—on their own social media and in multiple reports—that the clips and videos are hoaxes. Even after denials and clarifications, the outrage persisted. Educated groups, such as university professors and professionals, even shared the deepfake video of Sri Mulyani. However, the denial competed with widespread economic discontent and perceptions of policy neglect toward educators and taxpayers.

The Indonesian late August protest marked the climax of polarisation within society that had been building since the previous election. When we began monitoring hate speech in the presidential campaign in September 2023, we consistently detected two principal axes of polarisation. The first one is economic polarisation– tension between privileged groups and the working class/vulnerable middle class. The second one is Anti-elite/political dynasties – clashes between perceptions of political elites and dynasties versus the people. This polarisation was not isolated, but rather part of a larger networked polarisation, a term we use to describe the interconnected web of social, economic, and political divisions that fuelled the protests.

These polarisation trends continued throughout the 2024 general and regional elections into 2025, culminating in the latest demonstrations rejecting the lavish lifestyles flaunted and glorified by parts of the political elite amid the public’s challenging economic conditions. Thus, the August 2025 protests were not an anomaly. They reflected the accumulation of public frustration that has grown for at least the last two years, at the intersection of socio-economic class polarisation and anti-elite sentiment.

Moreover, anxieties over the economic slowdown, layoffs, and frustration with government performance primed citizens to read events through a us-versus-them lens. In such conditions, mis/disinformation is not persuaded by facts so much as by resonance: a deep fake that seems to confirm lived experience can feel “truer” than an official correction. This is where the power of social media comes into play, amplifying these emotions and making a fabricated clip of a top official allegedly belittling teachers’ travel so far, and why the death of Affan Kurniawan, an online motorcycle taxi driver, under an armoured police vehicle, catalysed grief and fury on the streets. The message fit the moment.

According to Moscovici’s Social Representations Theory, people make sense of new claims by fitting them into familiar stories. The deepfake did precisely that. It was anchored to a well-worn “elites vs ordinary people” script, so many viewers treated it less as a factual statement than as a recognisable type of disdain. It also objectified a diffuse grievance—teachers and other working-class people feel undervalued—into a vivid, shareable image. Once a grievance takes on a concrete form like this, technical debunks rarely move the needle. The question of authenticity seems secondary because the clip appears to embody a truth that people already live by.

Affan Kurniawan’s death then confirmed that story in place. Being struck and killed by an armoured police vehicle during a dispersal near parliament turned an abstract complaint about unfairness into a visceral narrative of harm and accountability. The event re-objectified public meaning, as anger, sadness, and fear gathered around “Affan” as a symbol that organised talk and expectations—justice, reform, restraint. Powerful images travel; they reinforce a core of justice, dignity, and safety while pushing disputes (like whether the video was real) to the margins.

During that time, netizens expressed their feelings with emojis such as a police siren (359.302 mentions), followed by a wilted flower (277.770), an exclamation mark (272.205), and a loudly crying face (244.281). The police siren emoji was primarily used in posts warning that President Prabowo had authorised the police and military (TNI) to discipline citizens, which many saw as a threat to freedom.

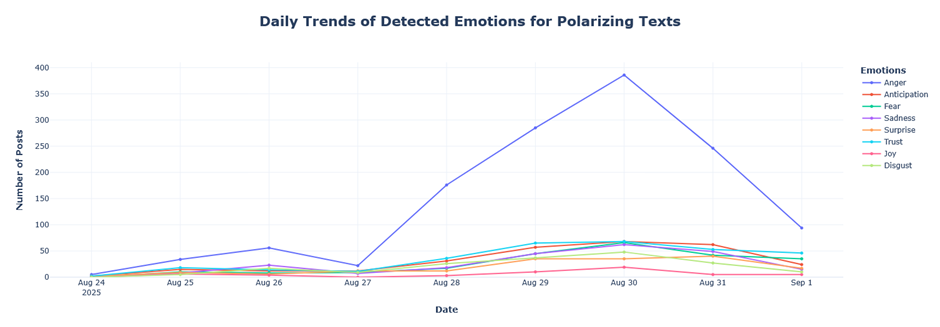

Our latest analysis of online conversations on X reveals the dynamics of public emotion, toxicity, and polarisation in online discussions during the protest. Additionally, it confirms that anger was the leading effect (47.3%) of polarisation (see Figure 1). From nearly 10 million digital conversations across social media and news media, the research team analysed 13.780 original posts to capture the authentic expressions of netizens. The results show that toxicity rose to roughly one-third of posts at the peak, and polarisation was present in about one in five spikes that tracked moments of offline escalation.

Figure 1. Trends in netizen emotions expressed via polarising texts

Another finding shows that public emotions moved dynamically: from anticipation at the beginning of the actions, peaking in anger on August 28–30, and then blending with sadness, fear, and surprise. Social media served as the primary platform for articulating citizens’ collective emotions, shaping and amplifying the narrative of “the people versus the elite” and expanding the protest base. In the context of the 17+8 Movement, anger that had been dominant during the riots shifted into joy and neutral sentiment. With a focus on concrete solutions and symbolic solidarity, this digital movement transformed working-class anger into a narrative of solidarity, togetherness, and hope, demonstrating the power of social media in shaping public discourse.

The network effects matter just as much as the representations. Peaks in anger mapped tightly onto protest escalations; hashtags that framed institutions as enemies in Figure 2 (#bubarkanDPR or #DisbandDPR, #PolisiPembunuhRakyat or #PoliceKillsPeople) amplified a moralised binary, reducing the space for “in-between” positions. However, the same network that radicalised anger also made possible a pivot to constructive frames: as the “17+8” list circulated, posts expressing joy, trust, and anticipation rose, signalling that participants could re-anchor the movement around practicable reforms rather than solely around denunciations. The duality matters: networked polarisation is not merely dividing and radicalising, but it can also be uniting and constructive when frames invite broader publics into practical, future-oriented tasks.

Figure 2. Most-used hashtags on X during the public protests

Nevertheless, representations alone do not mobilise. For tipping points, Moscovici’s minority influence matters. Social change rarely begins with the masses; instead, it often starts with active minorities—the “rebellious few” who consistently put forward a dissenting line, maintain internal consensus, and operate with autonomy from the dominant view. In the current protest, that role was played by gig workers, student groups, labour organisers, educator networks, civic creators, and rights advocates who kept hammering the same value-laden claims—about economic dignity, respect for educators, and limits to state force—before and after the deepfake, and then again after Affan’s death. Their insistence provided a stable scaffold that others could anchor to as emotions surged, underscoring the crucial role of these minority groups in driving social change.

Indonesia’s late-2025 protests were not simply the tale of a fake video and a tragic death. They were a case study in how representations give mis/disinformation a foothold, how minority influence supplies the engine of change, and how networked publics amplify both division and solidarity. The initial framing—polarisation across class and dynasty lines, economic strain, and frustration with governance—is precisely what made the falsehood “work”: it resonated. It continued to resonate through the regions –with Filipinos and Nepalis, where working-class anger translated a “local” Indonesian scandal into a shared South and Southeast Asian grammar of grievance and mobilisation.

Acknowledgement–the analysis was done by the team from Monash Data & Democracy Research Hub. The full report is available here.

Ika Idris is Co-Director of the Monash Data & Democracy Research Hub and a specialist in social media analytics. Since 2019, Ika has trained officials across major Indonesian government agencies on strategic public communication and social media analysis.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.