Decoding Russia’s Position in the Israel-Hamas Conflict

Russia’s once friendly relationship with Israel has soured demonstrably, with public support for Hamas now unquestionable. This move represents a broader geostrategic aim that attempts to position Russia as a peacemaker and the ongoing US-Israel-western response as the problem.

In the ongoing Israel-Palestine crisis, Russia has notably adopted a pro-Palestinian stance. Speaking at a meeting in Moscow, President Vladimir Putin said,

It’s easy to throw a spark, very easy. With the horrors happening there, it’s easy to do…When you look at the suffering and bloodied children, your fists clench and tears come to your eyes. This is the reaction of any normal person. If there is no such reaction, then a person does not have a heart, it is made of stone.

Experts suggest Putin is leveraging the Israel-Hamas conflict to escalate what he frames an existential struggle with the West for a new world order. The delay in his response to Hamas’ attacks didn’t go unnoticed, and when he finally spoke, the blame was directed at the United States for a perceived failed Middle East policy. His accusation that the US has attempted to “monopolize” peace initiatives, ignoring viable compromises, introduces a new layer of geopolitical tension. Putin’s additional claim that the US has neglected Palestinian interests positions Russia as a vocal advocate for Palestinian rights, marking a significant shift in Russian Middle East policy.

Despite being part of “The Middle East Quartet” (a grouping of- the United States, Russia, the United Nations, and the EU, established in 2002 for mediation of Israel-Palestine peace process), Russia’s criticism of US policy indicates a desire to distinguish its stance from that of its international counterparts. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov’s emphasis on diplomatic efforts has attempted to portray Moscow’s position as a commitment to conflict resolution. Moscow aims to position itself as a potential peacemaker, seeking to enhance regional influence.

Russia’s response to the ongoing crisis is guided by two main imperatives, immediate and long-term. The immediate rationale for its overt pro-Palestinian stance arises from the ongoing confrontation with the West. Facing economic and political sanctions, Russia seeks support from countries critical of Western unilateral sanctions and hegemony. This is a strategic move to counter US-led Western isolation. While Hamas receives support from various Middle Eastern countries, not all openly endorse it due to regional and ideological rivalries. Though this is not the case for Saudi Arabia and the UAE who avoid an overt anti-Hamas stance due to popular domestic sympathy for Hamas and Palestine.

The long-term imperative of Russia’s Middle East policy is the strategic alignment of its interests while avoiding unnecessary obligations. Russia aims to prevent previous mistakes of favouring one party at the expense of another in the complex Middle East region. During the Cold War, Russia supported pan-Arab socialism, risking its position against Saudi-led monarchies, and eventually relegating it a non-entity in the region. The goal is to maintain flexibility and adaptability in Middle Eastern geopolitical setting to safeguard its strategic interests in the region.

Russia’s Middle Eastern Engagement

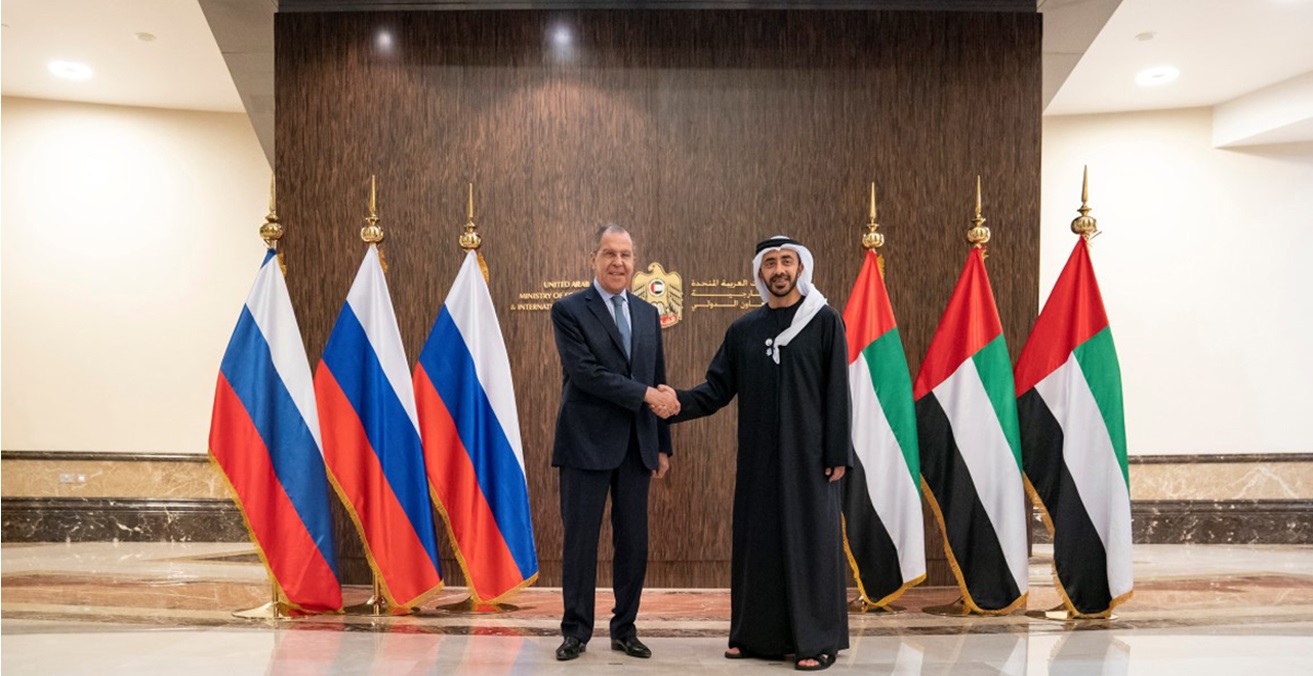

After the collapse of Soviet Union in 1991, Russia entered a two decade decline in its strategic policy making in the region. The Kremlin made a comeback only in 2015 when it intervened to safeguard the Assad regime in Syria. Since then, Russia has emerged as a significant regional power broker, and its self-appointed role has extended beyond Syria to seeking a voice in the conflicts in the Mashreq sub-region, on the Palestine-Israel issue, and on the situation in Lebanon. At the same time Russia has cultivated strategic partnerships with Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt.

While Syria is the only Arab nation openly supporting Russia in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, Saudi Arabia has been working closely with the Kremlin to manage oil production, effectively controlling both the oil market and prices. The UAE has served as a secure location for Russian capital. Meanwhile, Egypt has chosen to remain neutral in the Russia-Ukraine war and has resisted pressure to supply weapons to Kyiv. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have also played a significant role in the exchange of prisoners between Russia, and Ukraine. By adopting a policy of “positive neutrality” Arab nations have been able todevelop cooperation with Russia in strategic resource sectors.

The Ukraine War has also triggered a major shift in Russia’s relations with Iran. An alliance has flourished through Iran’s robust military and political support, and through their shared support for anti-Western policies and posture.

Russia-Israel ties, by contrast, have sharply declined, even before the 7 October invasion of Hamas and the subsequent Israel-Hamas war. In 2021, the Russian Ministry of Justice moved to shut down the Moscow office of the Jewish Agency for Immigration, an action Prime Minister Yair Lapid warned would negatively impact the relations between the two countries. Russia’s decision may have stemmed from Lapid’s condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine during his time as Israeli foreign minister. Stability returned with Netanyahu’s re-election in December 2022, partially due to his positive relationship with Putin. Approximately 20 percent of Israelis are Russian-speaking, and the two nations foster strong cultural bonds. Prior to 2022, Putin was considered one of the most Jewish-friendly leaders in Russian history, with anti-Semitism in Russia viewed as a phenomenon of the past. Despite strong economic integration, including US$1.72B on export from Russia to Israel in 2021, Tel Aviv’s alignment with Washington has restricted the depth of the partnership.

Meanwhile, Russia’s refusal to designate Hamas as a terrorist organisation has added further friction to the bilateral relationship with Israel. In the 1990s, Hamas was designated as “Islamic fanatics,” a posture that shifted with Putin’s coming to power in 2000, and after Hamas’ 2006 electoral victory. Moscow now regularly hosts Hamas delegations, with the latest occurring on 19 January. This early policy shift was partly driven by the need to maintain peace on the Russian southern frontier, particularly in vulnerable North Caucasian republics where there are significant Muslim populations. About 12 percent of Russians are Muslims, constituting the majority in several regions, and an active anti-Russian Islamist insurgency in the area, linked to international Islamist forces, raises concerns. Containing the spillover of radical Islamic ideology and turbulence on Russia’s borders is a key internal security priority.

Russia’s approach to the conflict has unsurprisingly drawn criticism from Israeli officials. The reception of a Hamas delegation in the aftermath of 7 October, Russia’s questioning of Israel’s actions, and the differences in strategic alliances have escalated tensions between the two countries.

In sum, Russia’s evolving Israel-Hamas strategy is a calculated move by Putin to challenge US dominance and establish a multipolar world order, one where the US and the EU are diminished. It signals Russia’s willingness to position itself as a major pole in this multipolar framework. The two-front engagement by Western forces along the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas axis has emboldened Putin’s ambition. Of course, stance carries risks. Instrumentalising Hamas, along with the resulting chaos in the Middle East, may have spill overs for Moscow, especially considering Russia’s history of facing terrorist threats. Amid international isolation following the Ukraine invasion, Israel has notably refrained from sanctioning Moscow or arming Kyiv, though this may now also change.

Rupal Mishra and Ankur Dixit are doctoral candidates at the Centre for Russian and Central Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.