In light of the ongoing military escalation between India and Pakistan, addressing the enduring violence in Kashmir requires a dual strategy. Both countries should adopt initiatives focused on economic development and youth engagement and pair it with efforts to rebuild trust in governance and democratic institutions.

On 22 April 2025, Baisaran Valley near Pahalgam in India witnessed a deadly terrorist attack that left 26 dead and over 20 injured. The assailants reportedly targeted victims based on their non-Muslim religious identity, asking them to recite Kalma and checking for circumcision before executing them at close range. Among the dead were newlywed military officers, a Christian bank manager, and a local Muslim pony handler who tried to protect the tourists from the attackers.

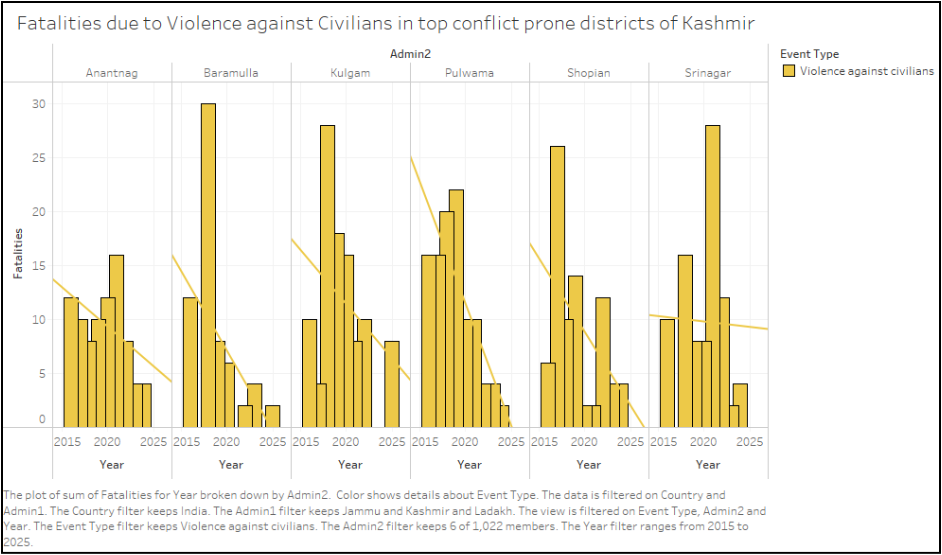

Violence against civilians has significantly reduced in Kashmir in the past ten years and empirical data confirm this claim (See Chart 1).

Source: The chart is prepared by the authors using the Armed Conflict Location & Events Data Project (ACLED)

However, this massacre, the deadliest since the 2008 Mumbai attacks, has reignited fears about the region’s fragile security and the resurgence of terrorism. Initial claims of responsibility by The Resistance Front, a Lashkar-e-Taiba proxy, were later retracted, adding to the confusion and highlighting the complex web of insurgent activity in the area.

The attack has also escalated military tensions between India and Pakistan, with India accusing Pakistan-based operatives of orchestrating state-sponsored terrorism. In a strong and decisive response to the terrorist attack in Pahalgam, India has suspended the Indus Waters Treaty, expelled Pakistani diplomats, shut its borders, and launched precision strikes targeting terrorist camps across the Line of Control. Pakistan, in a desperate and aggressive retaliation, suspended the 1972 Simla Agreement, closed its airspace to Indian flights, and escalated hostilities through cross-border shelling and drone attacks.

The “Dyadic Inter-State War Dataset” by Correlates of War project indicates that India and Pakistan have been involved in a protracted conflict since 1949, characterised by absence of stable peace. The peace scale criteria for state relationships, as theorized by Diehl et. al. in 2019, indicates that the India–Pakistan relationship has historically oscillated between severe and lesser rivalry. However, all conflict scholars agree that peace is not just the absence of war. Traditionally, the Indian Government has focused its energy and resources in establishing a negative peace in Kashmir, characterised by the successful reduction of conflict in the region. The publicly available Armed Conflict Location & Events Data Project (ACLED) on instances of violence and fatalities indicates this declining trend of terror activities. Having said that, the positive peacebuilding efforts in the region have had their limitations. The Positive Peace Index defined as the “attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies” ranks India at 87th position (overall PPI score: 3.25) and Pakistan even lower at the 128th position (overall PPI score: 3.64), indicating that positive peace is perpetually disrupted in both the countries.

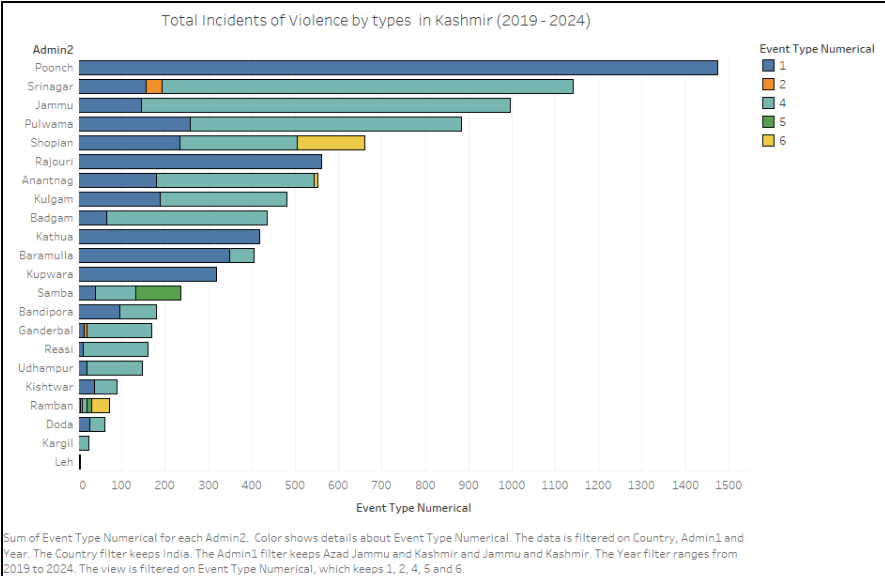

The abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019 revoked Jammu and Kashmir’s special constitutional status and brought it fully under Indian federal authority. This decision was later upheld in the Indian supreme court calling it constitutionally viable. Since that time, the central government in New Delhi has emphasised Kashmir’s full integration into the Indian Union as a pathway to lasting peace, economic investment, and democratic consolidation. In the past two years, these efforts have appeared to yield some dividends, particularly in the tourism sector. Tourist arrivals in Kashmir surged, boosting employment and business opportunities, and local businesses began to hope for sustained economic revival. While these developments indicate a consolidated effort for positive peacebuilding in Kashmir, the underlying instability has persisted in pockets. Instances of violence, including fatalities due to armed clashes and riots have indeed been reduced in the valley since 2019, but it has not been eradicated completely (See Chart 2).

1: Battles, 2: Explosions, 4: Riots, 5: Strategic Developments 6: Violence against Civilians.

Source: The chart is prepared by the authors using the Armed Conflict Location & Events Data Project (ACLED)

The recent terror attack in Pahalgam brutally aims to disrupt this trend. Moreover, it displays the harsh reality that increased tourist footfall and investment alone have not succeeded in neutralising deep-seated grievances. Nor have they dismantled the entrenched networks of militancy–a sobering reminder that underlying instability remains unresolved. Thus, violence remains an omnipresent threat to the positive peacebuilding efforts that New Delhi had envisioned for Kashmir in the recent past.

Our analysis on fatality data across Anantnag, Baramulla, Kulgam, Pulwama, Shopian, and Srinagar from 2015 to 2025 indicates a visible decline in civilian deaths, particularly after 2020. However, this decline must be interpreted with caution. During the earlier years, notably between 2018 and 2020, these districts experienced alarming spikes in violence, with fatalities in Baramulla and Srinagar peaking above 30 civilian deaths. The timing of this escalation coincided with significant political shifts, most prominently the Indian government’s revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomous status in 2019.

Our analysis further reveals that while post-2020 trends show a measurable drop, fatalities have not been eradicated. In 2025, civilian deaths, though fewer, continue to be recorded across all six districts. This persistence points to an entrenched fragility and the mere reduction in casualty numbers cannot be mistaken for the restoration of peace. In fact, it risks masking the continued reality of insecurity faced by civilians in Kashmir.

ACLED Data shows that violence against civilians and armed clashes in Jammu and Kashmir peaked between 2017 and 2019, with major incidents like the Uri and Pulwama attacks. Since then, civilian fatalities have significantly declined in districts such as Anantnag, Baramulla, and Pulwama, with Pulwama nearing zero deaths by 2024. While these trends reflect improved security and effective counterinsurgency efforts, the 2025 Pahalgam attack highlights the continued threat of militancy and the need for sustained vigilance.

Despite the decline in large-scale violence following the abrogation of Article 370 and enhanced security measures, the persistence of isolated attacks highlights the fragile and uneven nature of peace in Kashmir. While increased infrastructure investment and a revival of tourism have raised hopes for stability, the security environment remains precarious, and complete peace remains elusive.

In light of the ongoing military escalation between India and Pakistan, addressing the enduring violence in Kashmir requires a dual strategy. Domestically, the government must complement security operations with meaningful political engagement aimed at addressing longstanding local grievances. Both countries should adopt initiatives focused on economic development and youth engagement and pair it with efforts to rebuild trust in governance and democratic institutions. Internationally, while India must firmly defend its sovereignty and counter cross-border terrorism, it should also intensify diplomatic efforts to hold Pakistan accountable for supporting militancy/terrorism, while proactively countering external narratives that legitimise violence. Lasting peace in Kashmir cannot rely solely on hard security; it demands the creation of an environment of positive peace—one that removes the social and political conditions in which militancy can take root.

Dr Garima Sarkar holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from McMaster University, Canada specialising in public policy and comparative politics with a focus on gender and political representation in South Asia. Her research explores the barriers women face in political candidacies, party politics, and electoral politics with a particular focus on India and the Asian region.

Dr Soham Das holds a Ph.D. in Political Science with Research Methods concentration and a Masters degree in Political Science from The University of Texas. He is an Assistant Professor at the Jindal School of International Affairs, with research interests spanning the fields of comparative politics, international relations, public policy, electoral politics, and social-economic inequalities.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.