The energy transition depends on critical minerals, but supply chains are vulnerable due to processing concentration in China. Australia can play a key role if it moves beyond raw material exports.

“Critical minerals” are defined as non-fuel minerals that perform an essential function in the economy, are challenging to substitute, and are subject to short-term supply chain risks or long-term availability concerns. The global transition from hydrocarbon resources to clean energy resources is expected to be highly mineral-intensive as clean energy technologies require more minerals than fossil-fuel based electricity generation technologies.

Clean energy technologies such as solar, wind, geothermal, electric vehicles, hydrogen, electric storage, and electricity networks rely on the availability of critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, rare-earths, copper, and platinum-group metals. There are concerns about the future availability of these minerals to meet the pace of the energy transition. Production of many of these minerals are geographically concentrated with perceived risks around market power that dominant players could exercise. This raises concerns about possible price volatility and supply chain disruptions to these minerals.

Australia’s resource abundance of critical minerals

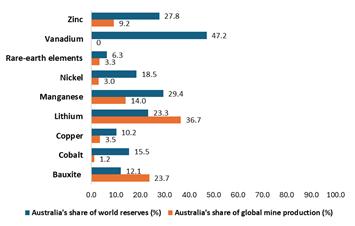

While most countries in the world prepare critical mineral lists to highlight the minerals that have vulnerabilities in their supply chains, Australia is one of the very few nations that prepares a critical mineral list to highlight the minerals it can supply to the world to tackle supply chain challenges. Australia has significant reserves of several minerals considered critical for the energy transition. Figure 1 shows that Australia has a considerable share of global reserves for some critical minerals and has potential to increase its share of global production.

Fig 1: Australia’s share of global reserves and global mine production for select critical minerals used in clean energy technologies. (Source: USGS, MCS 2025)

At present, Australia is a prominent mineral ore producer, with large share of its ores being exported to other countries for processing.

Concentration in processing: The bottleneck in global supply chains

Global supply chains for many critical minerals needed for clean energy technologies are geographically concentrated, especially at the processing/refining stage. For example, in the case of battery minerals such as lithium and cobalt, China dominates the processing of these minerals. In the case of rare-earths, China dominates production both at the extraction and processing stages. The perceived risks associated with a single country, China, dominating the processing of these minerals renders these supply chains vulnerable to disruptions. The most substantial bottleneck in the critical mineral supply chains is thus the concentration in mineral processing.

The seemingly obvious solution is diversifying processing of critical minerals. Nevertheless, the geographic diversification of processing brings with it a host of challenges. Though technology barriers exist only in the case of some minerals such as rare-earths, the more serious barrier is the ability of the rest of the world (ROW), including Australia, to invest capital and operate processing plants that can produce refined minerals that are price competitive. China’s industrial policy has led to easy access to cheaper capital, providing a crucial advantage to Chinese companies. In addition to this, analysing past data in the case of some minerals shows that China moves first relative to the ROW, sometimes building capacity to the point of global over-capacity.

Australia’s role in global critical mineral supply chains

Given the mineral resources that Australia is endowed with, it certainly has advantages that can be leveraged to contribute to resilient critical mineral supply chains. Australia can be a significant producer of critical mineral raw material for the energy transition providing it could increase and expedite investments in mines for the minerals needed for clean energy technologies.

In addition to investing in mines to produce ore, Australia can play a role in diversifying processing capacity for critical minerals. While China dominates critical mineral processing, it is important to recognise that China is dependent on other countries for raw materials. For example, the raw material production for cobalt refining is largely from the Democratic Republic of Congo and the raw material for lithium processing is supplied from countries such as Chile and Australia.

Attempts already made by Australia to set up processing infrastructure for lithium (Kwinana) and nickel have been unsuccessful, owing to competition from Chinese plants and Indonesian nickel plants backed by China. These case studies show that the path to moving up the value chain for Australia is not devoid of setbacks. It cannot be achieved through the support of government subsidies alone given China’s strengths. Australia is at a crucial juncture where strategic decisions need to be made for its way forward.

The importance of international cooperation

As concentration in processing is something the ROW faces as a whole, Australia can work together with other countries to take the lead in the diversification of the mineral processing sector. The Minerals Security Partnership that aims to diversify critical mineral supplies through international cooperation could be a starting point, but a lot more is needed to drive the mission ahead. Countries from the ROW should work together so that the burden of the challenges can be shared, and comparative advantages that other countries can offer can be utilised. Australia going it alone may not be in its favour given the high capital and labour costs, and strict environmental standards involved in setting up processing plants in Australia in comparison to China.

Between access to raw material and setting up processing infrastructure, it is a more difficult challenge to overcome a lack of access to raw material if viewed from a long-term perspective. China has overcome this challenge by being strategic in its approach to obtaining access to mineral raw materials. China continues to take efforts to diversify access to mineral ores in places such as Africa and Latin America. It may not be a wise strategy for Canberra to continue to only focus on mineral ore production going forward, at least in the case of minerals where China is its largest buyer. Either processing facilities need to come up elsewhere in the ROW, which Australia can cater to, or Australia should find ways to succeed in moving up the value chain.

For a country like Australia that is endowed with minerals, once technological barriers, challenges around labour, and capital costs are overcome, setting up processing infrastructure is achievable. The ability to sustain itself and withstand competition from China can be accomplished only if the ROW comes together with Australia to create market support by making diversification of mineral processing a priority. When geographic diversification in processing takes the lead, resilient mineral supply chains can become a reality.

Sangita Gayatri Kannan is a Ph.D candidate in Mineral and Energy Economics at the Colorado School of Mines.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.