A 10-minute video on X has been viewed eleven million times in the past six months. In it, senior members of the current UK Labour government acknowledge the claims of veterans of British nuclear tests in Australia and Kiritimati regarding health problems that many veterans—and their families—have suffered over the past 75 years.

These senior members include a range of members of parliament who have served as Deputy Prime Minister, Defence Secretary, and Armed Forces Minister. Most of the viewers are British. Eleven million is a very large slice of the British electorate that may be faced with a snap election sooner rather than later.

The Signs of Change

Recently, Prime Minister Starmer has taken time out from his many woes to write to 88-year-old veteran John Morris, promising to meet with him and his fellow veterans soon. This is Starmer’s first statement on the issue in four and a half years, 18 months of which he has been Prime Minister. It is as Prime Minister that Starmer undertakes “to ensure that the sacrifices of Nuclear Test Veterans are recognised.”

The UK government is slowly making thousands of documents relating to British atomic and nuclear testing in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s available for free download. There is an acknowledgement of “the trauma and distress experienced by those present during or affected by the events of the time” in the “WARNING” on the frontispiece of the UK National Archives website.

The government may be trying to resolve the issue before it reaches litigation yet again. However, this would still leave unresolved the question of Misconduct in Public Office—both before and during the period when 40,000 men were required to participate in the British tests, and in the decades that followed. This matter is currently the subject of a major police inquiry in England and could have significant implications for Australian veterans, Indigenous communities, and the general population, as well as their descendants.

Early Medical Insights

The hazards of radiation exposure were recognised early, particularly for vulnerable populations. No women were assigned to the British atomic and thermonuclear test sites in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, as the hazards of radiation exposure to foetuses had been studied in laboratory animals and were being recognised as a risk in radiography procedures for pregnant women.

Despite these findings, 40,000 servicemen, scientists, and civilian workers were sent to the desert test sites in Australia and to the coral sands of Christmas Island, now Kiritimati, in the Pacific. An estimated 14,000 of these men were from Australia, with several hundred more from New Zealand, Fiji, and Canada.

In July 1955, British geneticist J.B.S. Haldane stated in a letter to Nature that Sir John Cockcroft of the Atomic Energy Authority had “greatly over-estimated the simplicity of the problem.” Cockcroft, a 1951 Nobel Prize winner, had given what Haldane termed a “reassuring answer” to questions about the genetic hazards of radiation from nuclear and thermonuclear explosions disseminated to large distances.

Cockcroft replied in a short note that he had “emphasised the uncertainty of the biological data and the need for long-term genetic studies” and that, “since a Committee of the Medical Research Council has been appointed to study these problems, [he] will not pursue this problem further.”

The Prime Minister’s Response

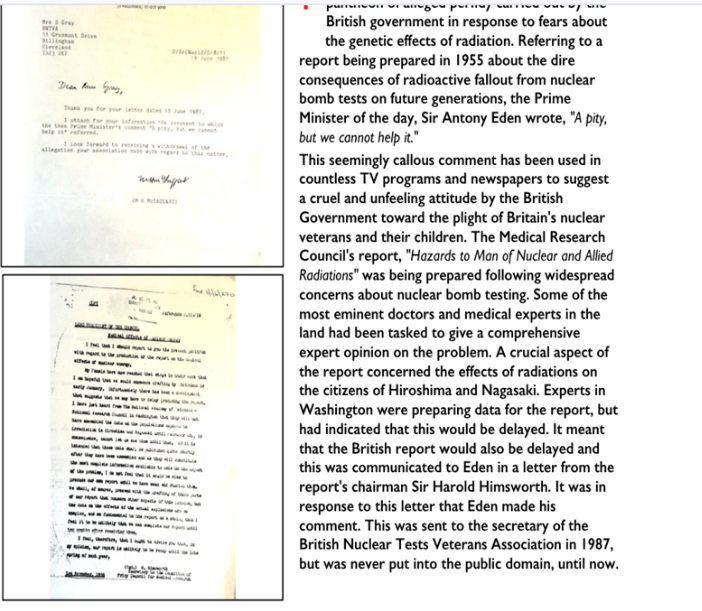

On November 14, 1955, a government official in 10 Downing Street wrote a note to the Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) stating, “The Prime Minister saw the report from Sir Harold Himsworth about the report of the Committee considering the Genetic Effects of Nuclear Radiation.” His comment was, “A pity, but we cannot help it.”

This comment has been widely quoted over the years—for example, in the House of Commons on 21 May 2019—as indicating that the Prime Minister was informed about the genetic hazards when he authorised the Mosaic and Buffalo series in Australia as a step toward the eventual detonation of the British H-bomb off Christmas and Malden Islands in 1957-58.

However, a recently discovered document dated 3 November 1955 from Sir Harold Himsworth, Secretary to the Committee of Privy Council for Medical Research, suggests a different interpretation. Addressed to the Lord President of the Council, it stated that the report on Medical Effects of Nuclear Energy had been delayed until late spring 1956 because it would be heavily dependent on US analysis of data from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Eden’s comment—”A pity, but we cannot help it”—likely referred to this delay in producing what was eventually published in June 1956 as The Hazards to Man of Nuclear and Allied Radiations.

Chapter IV considered the Genetic Effects of Radiation but noted that, “it must be realised that genetic studies inevitably tend to be slow and that sufficient knowledge on which to base firm conclusions will be accumulated only after many years of intensified fundamental research.” Results relied on the work of the US Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission report on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

An Ineffectual Response

The frequent references to genetic hazards in correspondence clearly indicate an awareness of their possible significance as the Eden government was preparing to test fully thermonuclear weapons in the Pacific, which had been conducted systematically throughout his second parliamentary term.

On 28 May 1956—six months before the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne—Prime Minister Anthony Eden chaired a meeting of ministers at 10 Downing Street. According to top-secret minutes released on Merlin, the Prime Minister convened the meeting “to consider whether the proposed announcement of the British nuclear tests to be undertaken in the Pacific in 1957 should be postponed on account of the forthcoming publication of the report of the Committee…to consider the genetic and other effects of nuclear explosions.”

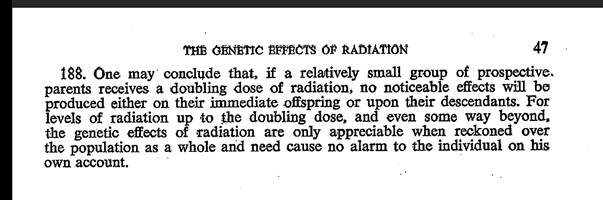

Nevertheless, the 1956 MRC report declared that barely a decade after the detonations at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, “For levels of radiation up to and doubling the dose, and even some way beyond, the genetic effects of radiation are only appreciable when reckoned over the population as a whole and need cause no alarm to the individual on his own account.”

At the Cabinet meeting on 28 May 1956 – midway between the two Mosaic detonations at the Monte Bellos and the four Buffalo detonations at Maralinga six months before the opening of the Olympic Games downwind in Melbourne – Sir Harold Himsworth reported that, “as a result of the thermonuclear explosions which had taken place a detectable amount of strontium was already being accumulated in human bones.” But he told the meeting that it could be concluded that “the genetic effects were negligible, even if thermonuclear test explosions continued at the present rate for a long period of years.”

Sir John Cockcroft, a member of the MRC Committee, attending the meeting for the Atomic Energy Authority, spoke next and said that he “accepted this conclusion” and that “the genetic risks were negligible.” Mark Oliphant recruited Cockcroft to become Chancellor of the Australian National University in 1961.

The Cabinet Minutes noted that the discussion then turned on the relation between the publication of this report and the proposed announcement of the Government’s decision to hold further nuclear tests in the Pacific in the spring of 1957. There was nothing in the report to justify cancelling or postponing this series of tests, and it was agreed that they should be held as planned.

Later Admissions of Harm

In 1957 the UK began the Grapple series of tests that resulted in the detonation of its first hydrogen bomb in 1958 in the Pacific off Christmas Island (now Kiritimati) and Malden Island.

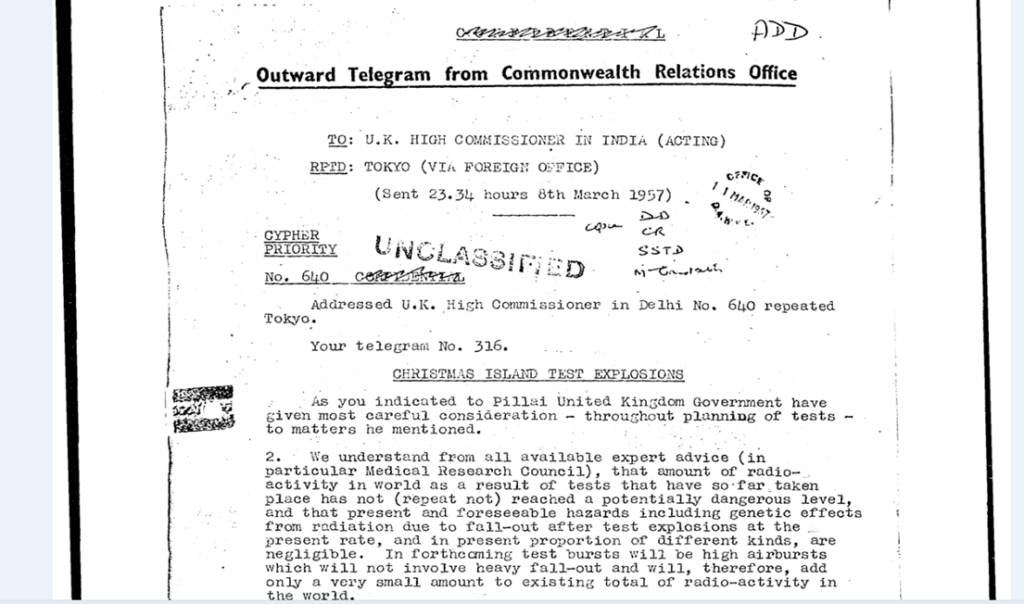

Among the Merlin database documents available online there is a Telegram from the Commonwealth Relations Office to the U.K. High Commissioner in Delhi (Acting) dated 8th March 1957 informing the recipient:

“2. We understand that all available expert advice (in particular Medical Research Council), that amount of radioactivity in world as a result of tests that have so far taken place has not (repeat not) recorded a potentially dangerous level, and that present and foreseeable hazards including genetic effects from radiation due to fall-out after test explosions at the present rate, and in present proportion of different kinds, are negligible.”

Titterton was the British physicist who detonated the first atomic bomb (Trinity) at Alamogordo in July 1945. He was the last British scientist to leave the US Manhattan Project and performed countdowns for the US Operation Crossroads tests in the Pacific. Professor Mark Oliphant later recruited him to the first Physics Chair at the Australian National University, and he became Chair of the Australian Atomic Weapons Safety Committee. His book was published virtually simultaneously with the MRC report. It states, “there is found to be a dose level below which there is no apparent tissue damage.” It continues, “However, it is believed that genetic changes do not show this threshold, are almost wholly deleterious and are cumulative in effect.”

Titterton quoted a statement by Professor A.H. Sturtevant of the California Institute of Technology at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in early 1954: “There is no possible escape from the conclusion that the bombs already exploded will ultimately result in the production of numerous defective individuals if the human species itself survives for many generations.”

Misconduct in Public Office?

We can count on the fingers of one hand the number of times the 1984-5 Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia has indexed references to the genetic consequences of exposure to radioactive fallout. Far too many of the documents in the National Archives of Australia catalogue for the Royal Commission remain closed, marked “not yet examined.” How has that been allowed to happen for 40 years?

We should consider whether this decades-long neglect—from the concealment of risks before and during the tests, through the failure to conduct proper studies afterward, to the continued suppression of documents today—amounts to misconduct in public office..

The author has provided the following resources for readers seeking additional context: Facebook page for survivors of nuclear testing can be found here and a Youtube video regarding the Merlin database here.

These links are shared at the author’s request and do not reflect endorsement by the AIIA or Australian Outlook.

Sue Rabbitt Roff studied and taught at Melbourne and Monash Universities. She researched and taught at Dundee University Medical School, offering modules on the health effects of UK nuclear tests. Her publications are collated at the The Rabbitt Review including presentations to AIIA Victoria in 2022 and a seminar series convened by the Chief Historian of the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 2024.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.