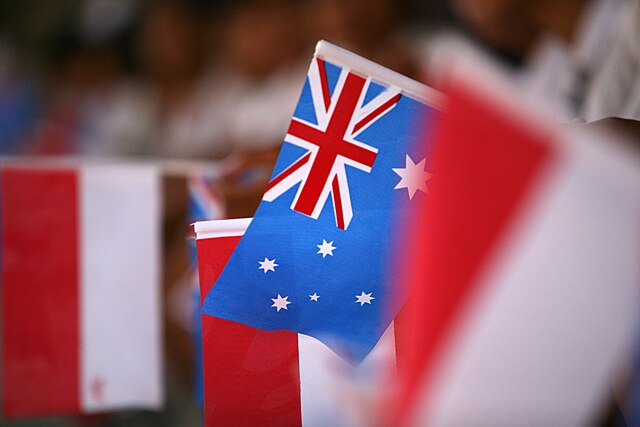

Earlier this month, Australia and Indonesia announced a landmark bilateral Common Security Treaty. The treaty is modelled closely on the 1995 Australia-Indonesia Security agreement. It will enable both countries to consult at the Leader and Ministerial level on a regular basis about issues affecting their shared security. Indonesia and Australia will also consult each other in the case of unfavourable challenges to either country, and, if appropriate, consider measures that might be taken, either individually or jointly.

Nevertheless, Indonesia will not abandon its traditional non-alignment, and there will be no defence obligations in the Treaty. Instead, the Treaty will be a platform for deeper strategic trust and consultations.

For Australia, its largest and most powerful neighbour is Indonesia. The two neighbours share the world’s longest maritime boundary. Subsequently, close relations with Indonesia are a strategic imperative for Australia. This is especially the case since regional cohesion falters under the weight of US–China strategic competition and security challenges such as the territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and the Myanmar civil war. Australia is subsequently trying to navigate an increasingly multipolar order in the Indo-Pacific.

Traditionally, Indonesia’s primary foreign policy focus has been Southeast Asia and its northern borders. In contrast to Australia, Indonesia follows a non-aligned foreign policy that forbids it from joining any formal security alliances. However, it is also in Indonesia’s national interest to have a reliable and close defence partner, such as Australia, on its vast southern flank.

One of the key pillars of Indonesia’s non-aligned foreign policy is the protection of its territorial integrity. This pillar has been undermined in recent years by China’s growing assertiveness in Indonesia’s North Natuna Sea Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). China claims that the EEZ slightly overlaps its widely disputed nine-dash line, which, according to the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), has no legal basis under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Although in recent years, Indonesia have deepened bilateral ties with China, it remains wary of Beijing’s intentions and actions in the North Natuna Sea. Moreover, for Indonesia, closer security ties with regional partners like Australia are an ideal counterweight to China’s expressed ambitions in the region.

The Common Treaty realises the full potential of the bilateral security relationship, without needing a formal security alliance. It will likely strengthen bilateral cooperation in many traditional and non-traditional security areas. Nevertheless, through the Treaty, Australia should be more ambitious and try to make Indonesia a top bilateral defence priority.

For instance, maritime security cooperation should be at the forefront. Under the Treaty, Indonesian naval vessels could be rotationally deployed to Darwin and Perth, and Australian naval vessels could be rotationally deployed to Surabaya and Makassar. This would increase high-level maritime cooperation, training and operations between the two neighbours.

Joint maritime training and exercises would be particularly beneficial for Indonesian naval personnel stationed in the Natuna archipelago. In recent years, Indonesia has been modernising its long-neglected and understrength navy.

The Treaty deal should also embed regular joint patrols between Australia and Indonesia inside their respective maritime boundaries, or just outside them. These patrols could strive to address shared border security threats like illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, human trafficking, people smuggling, transnational crime, piracy, and natural disasters. Indonesia loses US$23 billion annually to IUU fishing, while Australia, with the world’s third-largest EEZ, is therefore wary of the growing IUU fishing threat. An Australia-Indonesia hotline could also be established to prevent illegal vessels from sailing into both Australian and Indonesian waters from either country’s territory.

Since 2002, the two neighbours have co-chaired the Bali Process on people smuggling, trafficking in persons and related transnational crime. The Bali process is the Indo-Pacific’s premier forum for addressing irregular migration.

Moreover, in the short to medium term, the Common Treaty should work towards establishing joint Australia-Indonesia naval patrols in international waters, including the Pacific and Indian Oceans and the South China Sea. It would be in both countries’ national interests to uphold international law and norms, particularly on questions of sovereignty, and especially under UNCLOS.

Indeed, the Australia-Indonesia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP) enshrines the advancement of the freedom of navigation, unimpeded commerce and the resolution of disputes by peaceful means, in accordance with international law, particularly under UNCLOS. Indonesia has finalised several border agreements with neighbouring countries, including Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia, over the last 10 years. All these agreements were carried out in accordance with international law, including UNCLOS.

Furthermore, Australia could seriously consider granting Indonesia access to Australia’s Cocos (Keeling) Islands naval base and airfield. The islands are strategically located in the Indian Ocean, midway between Australia and relatively close to Sumatra, Indonesia’s largest island. Thus, the Islands can be established as a staging for Australia-Indonesia maritime and air surveillance of key choke points through the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

Over the past 70-plus years, there have been highs and lows in the Australia-Indonesia strategic relationship. The 1995 Australia-Indonesia security agreement was torn up by Indonesia in 1999 after the Australian-led multinational intervention in East Timor. This was an all-time low in the bilateral relationship, but it recovered from the setback and has matured over time.

In the 2006 Lombok treaty, the two countries recognised each other’s territorial integrity, and they upgraded their strategic ties to a CSP in 2018. Under last year’s Australia-Indonesia defence cooperation agreement, the two neighbours will ramp up joint military exercises and training to unprecedented levels and allow both nations to operate from each other’s countries for mutually determined cooperative activities.

Indonesia is set to reach new heights of economic growth and confidence in the coming years. This will likely make it a more active player in shaping the international rules-based order. Amid growing unpredictability in the Indo-Pacific, the Common Treaty has laid the foundations for a solid Australia-Indonesia security relationship. Australia should now use this advantage to advance the defence relationship to the highest possible level.

Ridvan Kilic holds a Master’s degree in International Relations from La Trobe University. His research interests include Australian and Indonesian foreign policy, the Australia-Indonesia bilateral relationship, and ASEAN regionalism. Ridvan’s work has been published in the Lowy Institute Interpreter, The ASPI Strategist, Australian Outlook, The Diplomat, Indonesia at Melbourne, the East Asia Forum, South Asian Voices, 9DashLine and the ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute Library.

This article is published under Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.