Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Tokyo came at a pivotal moment when India-Japan relations face unprecedented strain from conflicting positions on Russia, China’s rising aggression, and Trump’s punitive trade policies that have upended traditional alliance structures in Asia. Despite these challenges, the two leaders unveiled an ambitious 10 trillion yen investment target and deepened security cooperation, signalling their determination to forge a new strategic partnership even as their foreign policy priorities increasingly diverge.

The 15th Annual Bilateral Summit

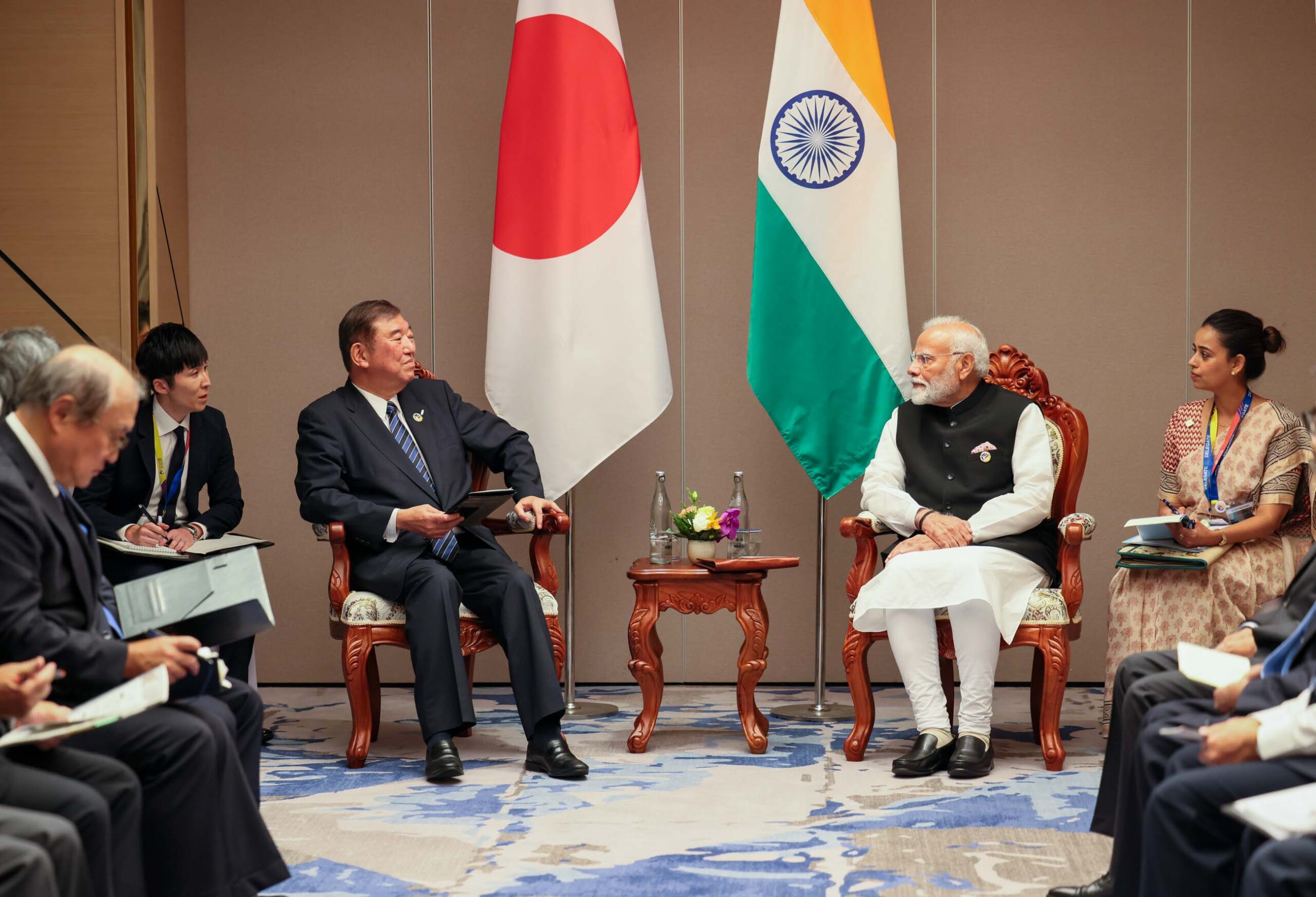

On his way to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Tianjin, China, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid a two-day official visit to Tokyo on 29–30 August to hold the 15th annual bilateral summit. This was Modi’s first summit with Japanese counterpart Shigeru Ishiba, who assumed office only late last year.

Modi and Ishiba reviewed progress in the “Special Strategic and Global Partnership”. They discussed a broad range of cooperation opportunities, identifying key areas of collaboration in the joint statement issued after the summit. The document outlines a shared vision for the next decade of partnership in defence and security, trade and the economy, technology and innovation, and people-to-people exchanges. This represents a significant update, introducing new objectives and goals beyond those set out in the 2015 “India and Japan Vision 2025” document signed by Modi and then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Changed Geopolitical Context

In the intervening decade, domestic and international geopolitical circumstances have shifted dramatically. Domestically, Japan has seen three prime ministers since Abe’s resignation in 2020, while its domestic politics remain volatile, with Ishiba’s decision this week to step down, adding to political uncertainties.. In contrast, Modi has remained in power since 2014, albeit with a reduced majority and dependent on a coalition. The changes in Japan’s leadership caused the momentum set by Abe over his eight-year tenure to wane. The annual summits became irregular, and only a few brief bilateral meetings were held on the sidelines of major multilateral meetings, such as the G7.

The war in Ukraine and India’s close ties with Russia have negatively affected Japan–India relations. In 2022, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida reportedly urged India to condemn Russia and adopt a stricter stance on the conflict, something New Delhi was unwilling to do given its history of close ties with Moscow. India’s volatile relationship with Pakistan, including its military actions earlier this year following a terror attack in Kashmir, has further complicated matters. Japan, being a key provider of foreign aid to Pakistan, has chosen to refrain from taking sides while still condemning terrorism.

More importantly, India–US relations have become strained, with President Trump imposing a 50% tariff, including a penalty on India for importing oil and arms from Russia, leaving their bilateral ties tense with no signs of easing. The Modi-Trump bromance of the past has soured, leaving the bilateral relationship strained. Japan, as a military ally of the United States, has maintained close bilateral ties with Washington since the two countries entered a security pact in 1951. Trump offered less onerous terms of trade with Japan, with a tariff of 15%.

Summit Outcomes and Agreements

Amid these domestic and international circumstances, Modi’s visit to Japan and Ishiba’s reception were notable. The two countries signed some thirteen agreements and memoranda of understanding, accompanied by a detailed joint statement issued by the two prime ministers.

India-Japan relations have seemingly entered a new era of economic engagement, with less emphasis on Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA), a defining feature of the relationship for most of the postwar period. In the 2015 and 2016 joint statements, ODA and ODA-supported projects were highlighted. In the latest joint statement, however, greater emphasis is placed on private investment, collaboration in new and emerging technologies, environmental management, strengthening defence and security ties, state-prefecture engagement, and human resource exchanges.

The statement highlights three priority areas: strengthening economic and trade ties, bolstering security and defence cooperation, and deepening people-to-people exchanges.

Economic Cooperation and Investment Targets

In 2022, Japan set a target of 5 trillion yen in public and private investment over five years. In contrast, the new statement sets a target of 10 trillion yen in private investment over the next ten years—a vote of confidence in the Indian economy and the market. The number of Japanese companies operating in India, primarily in the manufacturing sector, has increased over the past decade. The case of Maruti Suzuki Motors stands out: its market capitalisation on the Indian stock exchange is double that of its Tokyo-listed parent company, Suzuki Motors. Maruti Suzuki exports vehicles from India to Africa and the Middle East, where demand is growing.

Security and Defence Cooperation

Given Japan and India’s expanding defence and security ties, an updated security cooperation declaration consolidates all the relationships developed over the past decades. It establishes practical mechanisms for greater cooperation. The two are committed to a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific that is peaceful, prosperous and resilient. To this end, the two leaders expressed “serious concern” over the situation in the East China Sea and the South China Sea, a veiled criticism of China’s military assertiveness.

The document outlines several new security dialogue mechanisms, including an annual dialogue between their national security advisers. Both nations view security broadly and aim to collaborate on economic security to establish resilient supply chains for critical goods, notably semiconductors. During his visit, PM Modi and his Japanese counterpart travelled by bullet train to northeastern Japan to visit Tokyo Electron, a Japanese chip manufacturer in Sendai collaborating with India.

People-to-People Exchanges and Subnational Cooperation

In their joint statement, Modi and Ishiba emphasised the importance of collaboration in human resources and subnational contacts for economic, cultural, and other exchanges, which had been neglected in the past.

In a post on X (Twitter), Modi confirmed his meeting with sixteen prefectural governors and stated, ‘State-prefecture cooperation is a vital pillar of India-Japan friendship’. Both pledged to increase people-to-people exchanges by 500,000 personnel over the next five years, including 50,000 skilled professionals from India to Japan.

Implementation Challenges

The Modi-Ishiba summit brings new dynamism to the India-Japan relationship, but implementing its goals remains challenging due to several obstacles illustrated by the bullet train project. Primarily funded by Japanese ODA, the bullet train project has encountered numerous challenges, including delays due to land acquisition issues, escalating costs, and technology transfer challenges. These have created tensions in the relationship. Likewise, a plan to sell Japan’s ShinMaywa US-2 amphibious aircraft was abandoned due to disagreements over cost and technology collaboration.

Achieving the goal of 500,000 people-to-people exchanges and subnational engagement will also be challenging, given Japan’s limited experience with a non-Japanese workforce and the emerging opposition spearheaded by the Sanseito.

Strategic Divergences and Future Prospects

In geopolitics and foreign policy, India and Japan pursue distinct strategic priorities. Japan’s close ties with the US and its Western allies often diverge from India’s strategic autonomy, particularly in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, where India and Japan hold divergent views. Modi’s participation at the SCO, meetings with the Chinese leadership and hugs to Putin will be watched in Tokyo as much as in many other capitals.

Notwithstanding these challenges, Japan recognises India’s emerging geopolitical and economic weight on the world stage. At the same time, India desperately seeks Japan’s investment and technology to realise its aspiration of becoming a ‘developed nation’ by 2047, when it will mark 100 years of independence.

With a new prime minister set to take office soon, Japan will face fresh challenges. Still, there is a broad political consensus to strengthen relations with India. The intensity of the relationship, however, may vary depending on who assumes leadership.

Purnendra Jain FAIIA is an Emeritus Professor in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide, Australia, where he served as Professor in Asian Studies for twenty-five years. Author and co-author of fourteen books, he has published extensively in prestigious international journals, and his commentary on Asian affairs appears frequently on radio, TV and online platforms. Recognised for outstanding scholarship, Prof Jain received the Japanese Imperial Order of the Rising Sun Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon in 2020; was elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 2022; and a Fellow of the Australian Institute of International Affairs in 2024.

This article is published under Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.