The last decade has seen a substantial rise in scholarly writings on the value of diplomacy. American political scientist David Lindsey’s Delegated Diplomacy: How Ambassadors Establish Trust in International Relations contributes to this trend, arguing that diplomats remain important in the making of world politics and do so in surprising and paradoxical ways.

In books about diplomacy, scholars and practitioners look for different things. Scholars are attracted by good theories, while diplomats appreciate good stories. Either way, both want to know, for instance, the extent to which professional diplomats are still needed to represent governments abroad since technological advances allow political leaders to communicate directly with their counterparts; if a diplomatic presence is deemed important and necessary, where do states decide to be represented internationally; and should ambassadors be drawn from a professionally trained cohort of diplomats with few or no political appointees?

Lindsey’s Delegated Diplomacy casts much light on these questions. However, his focus is on whom do states think will best represent them abroad. Lindsey’s thesis is that the ideal diplomat is “partially, but not entirely, sympathetic to the foreign countries where they serve.” Such diplomats are likely to encourage better bilateral communications and therefore improve outcomes for both parties.

That thesis is developed with considered and nuanced claims. For example, while “diplomats should be sympathetic to their hosts,” they “should not be excessively sympathetic” to a degree that distorts their best judgement. Rather, diplomats should hold an “intermediate” sympathy level between the two countries. Wise leaders, Lindsey suggests, “choose diplomats with the appropriate level of sympathy (and thus credibility) for the circumstances they are expected to face.” However, in contrast, some readers may argue that “empathy” may work better than “sympathy.”

To support his claims, Lindsey skilfully deploys quantitative and qualitative methods, combining political science’s modelling instincts with the diplomatic historian’s gift for telling a good story. To demonstrate quantitatively that “senior [US] diplomats are responsible for nearly all consequential diplomatic activity,” he analyses Foreign Relations of the United States and declassified Cold War-era entries in the US President’s Daily Brief, to argue that the influence of senior diplomats is “almost exclusively” in communications with other governments.

In what is perhaps the best part of the book, Lindsey provides a fascinating qualitative comparison of two of President Woodrow Wilson’s ambassadors: Walter Hines Page in London (1913-1918) and James Gerard in Berlin (1913-1917). Both were non-career appointments. As a strong anglophile, Page was known for his decades-long connections and friendships in Britain. Thus, he enjoyed considerable credibility with key members of the British Government, such as Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey. These connections allowed Page to substantially shape and interpret instructions on multiple occasions during the war in ways that served both the United States and Britain. Page is portrayed as a “sympathetic ambassador” and was therefore, in Lindsey’s theory, highly effective in managing the bilateral relationship at critical moments.

In sharp contrast, Lindsey casts Gerard as an “unsympathetic–at times antipathetic” and “entirely superfluous” ambassador to Germany. Gerard “held no pro-German sympathies” and represented American interests in Berlin in such an unfiltered, unquestioning way that they were interpreted as being anti-German. Consequently, he had no independent credibility with the German Government, and his role was reduced to a mere messenger of diplomatic communications between the two governments when much more was needed.

Thus, the sympathetic Page in London contributed to the successful management of Anglo-American relations, whereas the unsympathetic Gerard in Berlin was a factor in the breakdown of US-German relations. Case studies involving contemporaneous ambassadors from the same country is a promising research angle that could be widely adopted.

Lindsey’s methods evoke some questions. For example, while effective communication is clearly an important task of diplomacy, diplomatic work also involves reporting, representation, negotiation, and crisis management. In addition, the Foreign Relations of the United States series that documents major US foreign policy decisions, does not capture all that has been written by American diplomats. Lindsey also places a heavy wager on two cases from a 100 years ago, under a Democratic president, who were non-career ambassadors. While ambassadors are the most important diplomats, there are many others below that rank who have influenced the course of history, a good example being George Kennan’s famous Long Telegram, laying the basis for Cold War containment, sent from the US embassy in Moscow in 1946.

Those considerations aside, Lindsey’s book importantly turns our attention to a notion–disparaged by practitioners and neglected by scholars–known as diplomatic “localitis.” Localitis is the condition whereby diplomats are said to adopt the perspectives of the government and society of the receiving state, as a result of having been posted to a capital for too long or having some other deep connection to the host country. Localitis is pervasive in the diplomatic ecosystem and is extensively referenced, albeit anecdotally, in diplomatic memoirs. Most diplomatic services go to great lengths to avoid it by, for example, strictly limiting the length of postings and encouraging home leave. However, the “condition” has rarely, to my knowledge, been systematically theorised or, for that matter, has its opposite–when diplomats develop an extreme dislike for the host government and society.

While Delegated Diplomacy is not about localitis per se, its focus on what motivates political leaders when they choose their nation’s ambassadors implies a more subtle way to consider the condition–in the right proportions–as a positive. For starters, the diplomatic memoir literature is replete with accounts of diplomats broadly interpreting their instructions from home to manage a problem or crisis in the bilateral relationship where local knowledge is required. As Lindsey recognises, diplomats posted abroad “sometimes act at the clear direction of their superiors” at home, “but they often chart their own course.” Localitis is the application of the host-country’s perspective over time, rather than an occasional occurrence. Moreover, Lindsey’s line of argument helpfully highlights a loyalty paradox: a diplomat loyally serves the national interest by being less than entirely loyal to it.” The idea that diplomats have divided loyalties, almost as a requirement for effectiveness, is anathema to naïve realists and political leaders and indeed to most practicing diplomats. Yet, the idea is to be found in the classic accounts of the ideal diplomat from the French envoy and writer François de Callières in the early 18th century, to British diplomat Harold Nicolson’s much-cited work in the 20th century. In short, the ideal diplomat “balances the interests on both sides.” On this view, the idea of a clearly identified and fixed “national interest” becomes fuzzier.

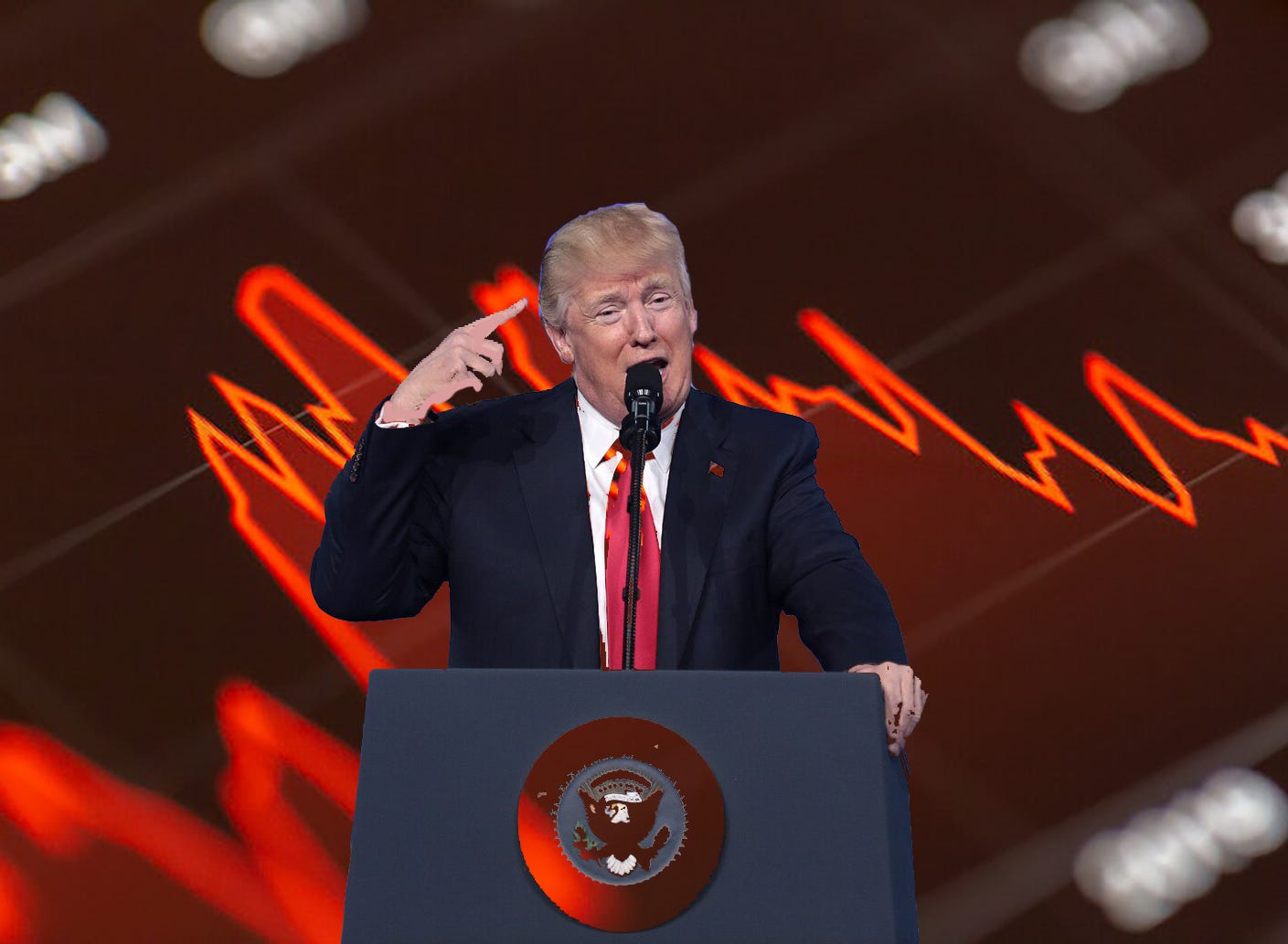

As the world processes the second Trump administration, Lindsey’s argument for a kind of measured localitis is already being tested. Trump’s sovereigntist, America First approach already portends the appointment of US ambassadors, career and non-career, whose loyalty to the president must be paramount, allowing little room for local knowledge and common-sense ambassadorial discretion, let alone reasonable consideration of the other side’s interests and values.

This is a review of David Lindsey’s Delegated Diplomacy: How Ambassadors Establish Trust in International Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2023). ISBN: 9780231209328.

Geoffrey Wiseman is Professor and Endowed Chair in Applied Diplomacy at the Grace School of Applied Diplomacy, DePaul University, Chicago. Wiseman was posted to Australian embassies in Stockholm, Hanoi, and Brussels and was as an advisor to the Australian Foreign Minister, Gareth Evans. He has also worked in the Strategic Planning Unit of the Office of the United Nations Secretary-General and as peace and security program officer at the Ford Foundation. He has taught at the University of Southern California and the Australian National University.

This review is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution. It was first published in Australian Outlook, July 2025.