The Russia-Africa Summit; the Wagner Group; and the Commonwealth Games

The future of Africa and the Commonwealth may be inextricably linked, with development the key focus for both. However, Russia’s presence on the continent, with its Wagner Group forces, are likely to disrupt necessary relationship building.

Given that in recent days the news of the world economy has been somewhat brighter, with inflation moderating and unemployment in Europe at its lowest level for years, it has been depressing to see headlines that suggest our politicians are still capable of serious errors and that the actions of the world’s No.1 war criminal, Vladimir Putin, go largely unchecked.

The Australian stories of note this week were Canberra’s increased financial and physical support for contingency planning against an American war with China and the decision by Victorian state Premier Daniel Andrews to pull out of hosting the 2026 Commonwealth Games. The world’s sporting media rightly saw it as rather shabby that the great southern city of Melbourne could not raise the money to welcome one of the most important events in the world athletic calendar. It leaves the organisers of the Games in a hole; it is not easy to find a location suitable to host such a large event at short notice. Moreover, the vacuum inevitably stimulates speculation that cancelling the Games could be a nail in the coffin of the great Commonwealth association.

Andrews’ decision is understandable given that the costs of hosting the event have soared almost three-fold from AUD$2.6 billion to at least AUD$6 billion – and perhaps AUD$7 billion. However, the news will hardly worry athletes from the 19 African and 11 Caribbean countries that are members of the Commonwealth, and whose backers and sponsors might find travel to Australia well beyond their pockets. They might prefer a venue closer to home, especially if the wealthier member countries of the Commonwealth could be persuaded to share the cost.

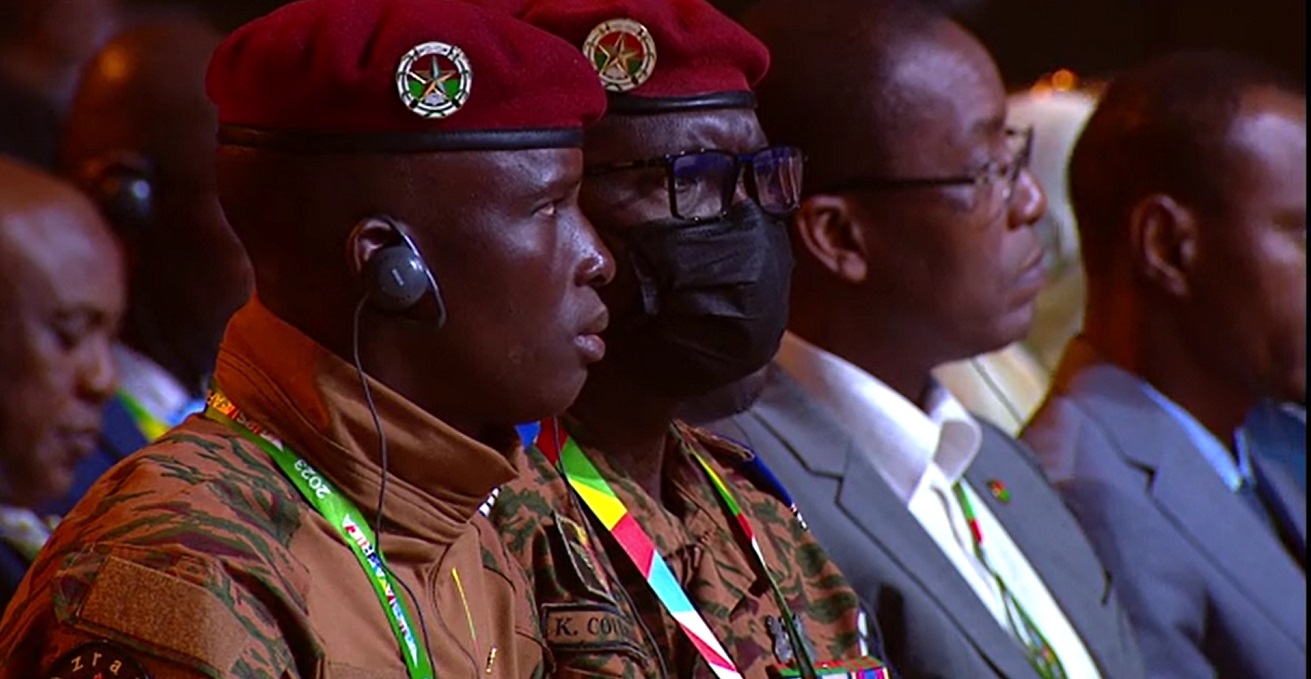

Meanwhile, this week at the second Russia-Africa summit in St Petersburg, Vladimir Putin has been seeking to engage African countries, including South Africa, deeper into his sphere of influence. The St Petersburg summit, which was to have been in Addis Ababa, was moved to Russia, no doubt at Putin’s request given that US president Joe Biden and others are pressing for more action to bring the Russian to trial for war crimes. With an attendance of just 17, it was a poor showing compared with the 43 who had been in Sochi in 2019, but nonetheless among those to make the journey were the presidents of Egypt, Republic of Congo, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, the vice president of Nigeria, and the prime ministers of Morocco, Somalia, and Tanzania.

Importantly, also attending was Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa, whose recent warmth towards Moscow is causing some angst among Western leaders. Ramaphosa told Putin: “Russia conducts its relationship with Africa at a strategic level with a great deal of respect and recognition of the sovereignty of African states. … We are very pleased that that spirit of co-operation continues and we appreciate very much your own disposition towards it.” Putin could not have hoped for a stronger endorsement of his summit. Putin’s plan to donate 52,000 tonnes of grain to six African countries met with less enthusiasm, with Ramaphosa stating that he did not come to seek gifts, and urged Putin to reopen the Black Sea to Ukraine grain exports.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of Wagner, the Russian-funded mercenary group which has supported the interests of the Russian government in several African countries, made the St Petersburg summit his first known public appearance in Russia since mounting an unsuccessful rebellion against Russia’s military leaders. The Wagner group and its hard-nosed mercenaries are now to be found across Africa, including in Libya, Sudan, Mozambique, and Mali, supporting terrorists and undertaking other disruptive activities. No wonder the UK Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee came out recently with strong criticism of the Sunak government for underestimating the growth of Wagner, which MPs claim poses a major threat to the United Kingdom and its interests. The United States and European Union have sanctioned roughly twice as many individuals linked to the Wagner group as have British lawmakers. The committee accused Whitehall of viewing Wagner in overwhelmingly European terms, miscalculating its activities in Africa, and imposing inadequate sanctions on entities and individuals linked to the group. “We are deeply concerned by the government’s dismal lack of understanding of Wagner’s hold beyond Europe,” says the committee’s chair Alicia Kearns.

Prigozhin welcomed the overthrow of a pro-Western leader in Niger after what he said had been a battle of the people against the colonisers. You might think that Prigozhin would have disappeared from view, Chinese-style, or be languishing in a Siberian torture chamber after seeking refuge in pro-Kremlin Belarus following his failed “rebellion,” but his old friend Vladimir clearly decided it was better to have him inside his tent than outside. Much of the funding for Wagner group mercenaries comes from Russia, and they in turn provide the muscle for many power struggles on the African continent. The Wagner presence in Africa goes beyond its “soldiers,” its coffers filled by its dealings in gold; perhaps no coincidence, then, that Putin is a very rich man.

It is clear Putin sees Africa as a continent where Russia can mount an assault on the influence of the West. He has already pulled out of his short-lived pact to allow the export of Ukrainian grain through the Black Sea and announced generous donations of wheat and other crops to hungry African nations. The timing is critical: the war in Sudan is in danger of further escalation and the repercussions of the recent coup in Niger could be widespread. For many years, the Russians have welcomed Africans for study at Russian universities, but there is now irrefutable evidence of the Russians exerting greater influence and presence on the continent itself.

The solution to Africa’s problems must lie with Africans. But they will need help and lots of it. Surprisingly, perhaps, Antonio Guterres, United Nations Secretary-General, remains optimistic. He told leaders of the 28th meeting of the African Union in Addis Ababa, “I am convinced the world has much to gain from African wisdom, ideas and solutions,” noting that the continent made the biggest single contribution to the UN peacekeeping force as well as for housing refugees, and Africa has some of the world’s fastest growing economies. He praises African leaders for adopting their own long-term plan – Africa 63 – the fundamentals of which involve avoiding crises and setbacks with a view to maintaining long-term gains.

This is where the Commonwealth of Nations could and should play a bigger role. It already uses its years of experience and expertise to run projects right across Africa, and its Charter, first proposed by Australia, encourages it to extend its knowledge to help fulfil the goals of the African people. Australian leaders will now, of course, have their eyes on what America sees as the threat posed by China, but they would be foolish not to realise that it is one of the richer countries best able to help its fellow Commonwealth members in Africa over some of its problems.

Colin Chapman FAIIA is a writer, broadcaster, public speaker, who specialises in geopolitics, international economics, and global media issues. He is a former president of AIIA NSW and was appointed a fellow of the AIIA in 2017. Colin is editor at large with Australian Outlook.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.