The Reality of Brexit: Empty Shelves and Troubles in Northern Ireland

The news of empty supermarket shelves and rationed petrol in the UK seemed to come as a surprise but yet did not surprise anybody. Yet, long lines for daily supplies is not the only Brexit-related issue facing the UK.

Why do we see empty shelves in supermarkets all over the UK? All but the most ardent Brexiteers assumed that the reality of Brexit would be bumpy at best, but experiencing a scarcity of everyday necessities is a dramatic turn of events. While there is still enough produce and petrol to supply the UK population, the UK transport industry lacks drivers to distribute these products within the country. As working conditions and pay within this industry are poor compared to those in other economic sectors, the UK transport industry has so far relied on drivers from elsewhere in the European Union, in particular from Central and Eastern Europe. These EU workers stopped coming to work in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the aftermath of Brexit, when the UK government decided to implement harsh, expensive, and cumbersome processes for (EU) foreigners to come to or stay in the UK. This stopped new workers from coming to the UK and drove a part of the existing workforce to leave the country. Yet, the worker shortage is not just a problem for the transport industry. Now that driving lorries has become more lucrative, fewer drivers are available for buses, and bus services are being cancelled. The National Health Service, too, relies heavily on a foreign workforce, leading to a shortage of doctors, nurses, and other medical staff.

Much of this has to do with why the UK population approved of Brexit. The argument that Brexit would give border control and, interrelated, jobs back to the UK population stood next to statements about UK’s financial contributions to the EU and the EU’s red tape. Political science research has shown that one central driver of the successful Brexit referendum was anti-immigration sentiment. Xenophobia and a sense that the UK was overrun by foreigners, as well as a hope that closing the borders would alleviate this perceived threat, were primary motivators for Brexit. Yet, the current crisis of staff shortages shows what happens when governments fully implement such proposed policy solutions.

It is exceedingly rare that national governments enact anti-immigration policies to this extent. When parties with such policy goals previously managed to enter government in other European countries – for instance, in Austria, Denmark, and Finland – maximalist policies that would result in a mass exodus of foreigners from the national economy are never enacted. Instead, such governments might opt for less disruptive measures, like tightening visa rules for specific countries, changes in work regulation or social welfare systems to disadvantage foreigners, or more symbolic policies. Brexit and the unique situation of the UK Conservative government under Prime Minister Boris Johnson, with its strong tendency to value public opinion over policy practicalities, have given us a unique opportunity to study what happens when anti-immigration stances are enacted closer to their logical conclusion. It shows that promising “easy solutions” to economic and social ailments, like removing the scapegoat “foreigners” from the country, come with insurmountable costs. After decades of globalisation, people from around the globe have become part of the social, cultural, and economic fabric of Western societies.

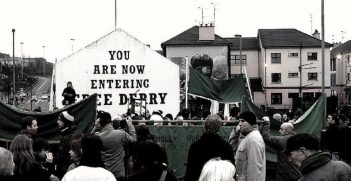

Yet, we should not forget that Brexit has even more consequences, and another crisis is brewing just below the radar of international media attention. While many focus on the glee of “told you so,” created by pictures of empty supermarket shelves and long lines in front of petrol stations, negotiations are currently taking place about the status of Northern Ireland. While Northern Ireland has technically exited the EU together with the rest of the UK, a normal border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is politically unacceptable for all sides. The peace on the Irish island is at risk in this instance.

The role of Northern Ireland is far from resolved, and negotiations are currently underway for the so-called “Northern Ireland Protocol” that is part of the Brexit agreement. The central question is about the location of the UK’s external border. Suppose this is between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. In that case, this will fundamentally disturb inter-Irish relationships and potentially open up the agreement that ended the violent conflicts of “The Troubles” in 1998. Thus, the current plan is that Northern Ireland stays within the EU’s single market. However, if the border on the Irish island remains open, this would necessitate a stricter border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. Such a border within the UK itself is highly troubling for the Unionists within the UK. Additionally, there are disagreements on a range of related questions, including whether the European Court of Justice has jurisdiction in Northern Ireland, which would impinge on UK sovereignty.

Most importantly, an internal UK border would be highly problematic for at least two reasons. First, any goods from England, Scotland, and Wales would need to be checked for their adherence to EU regulations at the Northern Irish border. Even for goods intended for Northern Irish consumption, this would be the case as it could not be guaranteed that they would not be shipped over the then-open Irish border. The bureaucratic and financial costs of such an arrangement would be immense. Second, such a border would have vast symbolic implications. The Troubles, the low-level civil war in Northern Ireland that only ended in 1998, were based on whether Northern Ireland belongs to the UK or Ireland. A strong border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK while the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was completely open could easily be perceived as a closer union of the two Irish nations. A resurgence of nationalism Unionists and Irish Republicans could have unforeseen consequences.

Thus, while much of the public attention is on labour shortages and their knock-on effects, there is another conflict brewing with potentially far-reaching consequences. The UK’s chief negotiator, Lord David Frost, has already warned that failed negotiations might lead to a triggering of Article 16 of the Northern Ireland Protocol. This article allows unilateral action in case of persistent economic, societal, or environmental difficulties and, thus, would suspend parts of the Protocol. Given the unique nature of this arrangement, suspending parts of the Protocol could have consequences ranging from further straining the EU-UK relationships to the breakdown of negotiations. Thus, Lord Frost’s statements are eerily similar to the negotiation tactics at the end of the original Brexit negotiations, which – as we now know for sure – has led to a whole range of suboptimal rules with unintended consequences.

Dr Annika Werner is Senior Lecturer at the School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University. Her research focuses on party behaviour, representation and public attitudes in the democracies of Europe and Australia and has been published in journals such as the Journal of European Public Policy, Democratization, Party Politics, International Political Science Review, Representation, and Electoral Studies. Her book International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament, co-authored with Duncan McDonnell, is published with Hurst/Oxford University Press.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.