Strengthening Philippine-China Relations: Rebuilding Economic And Social Trust

Trade and investment foster shared interests and motivations. For China and the Philippines, greater economic interdependence could provide a basis for rebuilding trust as tensions rise in the South China Sea.

In a 2019 opinion poll, 54 percent of Filipino respondents reported holding an “unfavourable view” of China. The survey’s findings were confirmed by Social Weather Station (SWS), a public opinion research organisation in the Philippines. Filipino respondents’ net trust ratings for China decreased from “poor” to “bad” in 2020, the lowest since the 2016 arbitration dispute between the Philippines and China over the nine-dash line in the South China Sea before the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Only nine out of the 53 SWS surveys performed since August 1994 have returned a “positive” net trust score for China.

One cause of Filipino respondents’ lack of trust in China is the ongoing territorial dispute in the South China Sea. 47 percent of adult Filipinos feel the Philippine government is not doing enough to assert its rights. Most Filipino respondents favoured enhancing Philippine military capability, holding joint military drills with allies, and putting the provisions of the Enhanced Defense Coordination Agreement and the Philippines-US Visiting Forces Agreement into effect. Filipinos have mixed views of Rodrigo Roa Duterte’s tight ties to China, with 31 percent of respondents feeling they have “much benefit,” 29 percent seeing “little benefit,” and 40 percent “undecided.”

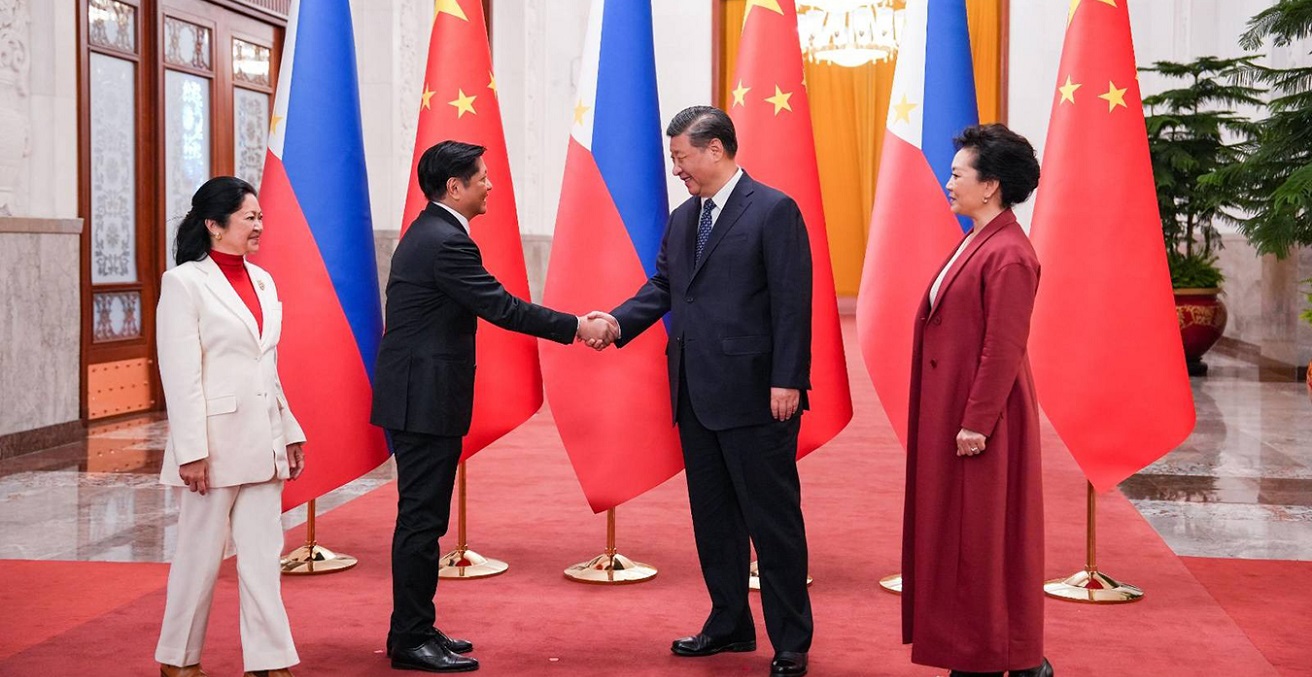

However, trade and investment relations between the Philippines and China are expanding, seemingly unaffected by China’s bad net trust rating. China is the Philippines’ top trade partner, third-largest export market, and top import supplier. Digital monolithic integrated circuits, nickel ores and concentrates, cathodes, refined copper, and semiconductor devices were the Philippines’ leading exports to China in 2022. Petroleum lubricants, components for producing semiconductor devices, and automobiles were the top Chinese commodities imported by the Philippines. During Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s three-day state visit to China in January 2023, the Philippines and China signed 14 bilateral trade agreements emphasising information and communications technology, tourism, agriculture, and fisheries, as well as economic and technical collaboration.

The Historical Basis

The current unfavourable views of China are reminiscent of how the Philippines’ Spanish colonisers felt about Chinese merchants and traders. Believing them to be emissaries of the Chinese imperial government, the Chinese merchants were seen as a danger to Spanish control over the colony and as having the potential to incite local opposition to colonisation. Following a “divide and rule” strategy, the Spanish encouraged negative sentiments toward the Chinese traders out of concern that the two groups may band together against them. Later, Filipinos adopted similar anti-Chinese sentiments.

Precolonial records reveal a thriving trade network between Chinese traders and the indigenous peoples, and later the Austronesian peoples, who inhabited the archipelago before the arrival of the Spaniards. Early on, the Spanish promoted the trade ties already in place because they believed that was preferable to institutionalising new economic practices. Manila was built as a transshipment port by the colonisers for carrying goods between ports in China and the far-off New World colonies. The Spanish, however, disregarded a key side effect the migration of Chinese traders into the colony. To address the matter, Spanish colonial rulers imposed severe immigration and taxing restrictions on Chinese migrants. Chinese people violently revolted 14 times, and the settlers were massacred as payback.

In the late 19th century, immigration laws were relaxed. Chinese traders took advantage and rose in economic power. However, the ethnic Chinese population of the Philippines found themselves in direct rivalry with the local elites. As a result, animosity toward Chinese immigrants and anti-Chinese economic nationalism started to spread around 1850. Such interracial conflict was encouraged fervently by the Spanish.

Even though many Chinese mestizos participated in the Philippine Revolution against Spain, hostility toward ethnic Chinese continued during American rule. Although American conquerors saw the Philippine colony as a stepping stone to the bigger Chinese markets, they imposed rules that hindered Chinese commercial methods. At the same time, the United States promoted respect for China’s administrative and territorial integrity and equal opportunity for international trade and commerce in China under the Open Door policy of then-US Secretary of State John Hay. However, the US also established a stringent policy on Chinese workers and merchants entering the US mainland. As a result, many ethnic Chinese emigrated to the Philippine colony, rekindling racial tensions with the native Filipinos.

After the Second World War, the Philippine Congress passed the Retail Trade Nationalization Act, which restricted retail trade to Filipino citizens and outlawed ethnic Chinese, bringing the conflict between ethnic Chinese merchants and the native Filipinos into the open. Ethnic Chinese contested the law on several grounds, including that it was against the treaty of amity between the Philippines and China. The Philippine Supreme Court upheld the law, citing that a treaty cannot limit the police power of the state. Further stoking mistrust were perceptions that ethnic Chinese merchants and residents were agents or unwitting instruments of mainland China to spread communism after 1949.

The subsequent warming of ties between Manila and Beijing under then-President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. helped to lessen the unfavourable impression. Marcos enacted a mass naturalisation law for ethnic Chinese Filipinos in 1974. China became a key trading partner, especially for importing oil and petroleum products.

Anti-Chinese sentiment has, however, returned with China’s increased naval operations in the South China Sea. The 1996 Mischief Reef Incident, the 2011 Chinese naval incursions on Philippine-claimed territory, the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, and China’s declaration of its nine-dash lines have led to a crisis in Philippine-Chinese relations and forced Philippine leaders to revive their military alliance with the United States. The situation also sparked concerns about the loyalty of the Filipino Chinese population. F. Sionil Jose, a controversial Philippine Nationalist Artist for Literature, urged Filipino Chinese to “either recognize their loyalty to China then go to China, or integrate.” Additionally, he exhorted Filipinos to recognise and eliminate the so-called Beijing collaborators, whom he called termites weakening the nation.

Strengthening the Relationship

Within this context, there are still opportunities for strategic engagement and cooperation between the Philippines and China, which would rebuild the social bridges that colonialism shattered and the current geopolitical situation have further weakened. To advance the main objective of mutual advantages for both countries, there is a need for the utmost efforts on both sides to deepen the strategic relationship through wide people-to-people contacts and open communications. The foundation of this discourse is the growing trading and investment relationship.

Trade and investment create economic interdependence. When the Philippines and China engage in economic activity that is mutually advantageous, they become invested in one another’s success since both parties stand to benefit from maintaining stable and cooperative connections. Economic interdependence incentivises trust and settling disputes via dialogue rather than hostility.

Further, economic interactions between Chinese and Filipinos can help dispel misunderstandings and assumptions as they get to know one another and learn about one another’s cultures, traditions, and beliefs. Regular commercial exchanges also provide opportunities for diplomatic dialogues, which can ease tensions and promote open communication and confidence.

Finally, the bilateral trade agreements between the two nations include clauses for dispute resolution procedures, like arbitration or mediation, which offer a formal and non-violent way to address disputes. By making sure that trade and investment take place in a fair and predictable environment, these mechanisms also help to foster trust.

Undoubtedly, trade and investment alone may not always ensure the development of trust, but they offer the Philippines and China a framework for promoting understanding, cooperation, and mutually beneficial outcomes.

Severo C. Madrona, Jr., PhD is a Professorial Lecturer at the Department of History, Ateneo de Manila University, the National College of Public Administration and Governance, University of the Philippines-Diliman, and the Ramon V. del Rosario College of Business, De La Salle University Manila. Email: smadrona@ateneo.edu

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.