South Korea and the Camp David Agreement in Japan’s Grand Strategy

In Japan’s grand strategy, it is a perennial challenge to keep Korea “threat free.” The Camp David agreement of August 2023 among Japan, South Korea, and the United States is a breakthrough that serves as a new institutional framework for Japan to cope with this challenge more effectively than ever before.

By virtue of its geographical proximity, the Korean peninsula is critical to Japan’s security. It is a geopolitical imperative for Japan’s grand strategy to keep the peninsula “threat free.” A fully threat-free Korean peninsula satisfies three conditions simultaneously. First and foremost, Korea should not fall into the hands of an Asian-continental great power hostile to Japan. In other words, Korea must be a solid buffer zone between Japan and the Asian continent. Second, Korean domestic politics should remain stable. Surrounded by great powers, a domestically divided and volatile Korea may precipitate a power vacuum, inviting competitive interventions by the external powers. Third, the Korean government should maintain a friendly diplomatic relationship with its Japanese counterpart. It is Japan’s geopolitical interest to have these three conditions fulfilled as much as possible.

In the divided Korean peninsula, Japan needs to keep South Korea threat-free. On the one hand, South Korea as a United States (US) ally largely satisfies the first condition of being a buffer zone in the Korean peninsula against North Korea, China, and Russia. On the other, and more challenging to Tokyo, is the question of how to induce South Korea to satisfy the second and third conditions—to become stable and Japan-friendly. For Tokyo, or any other governments for that matter, viable policy options are limited for this. After all, it is the people of South Korea who choose what kind of polity they want.

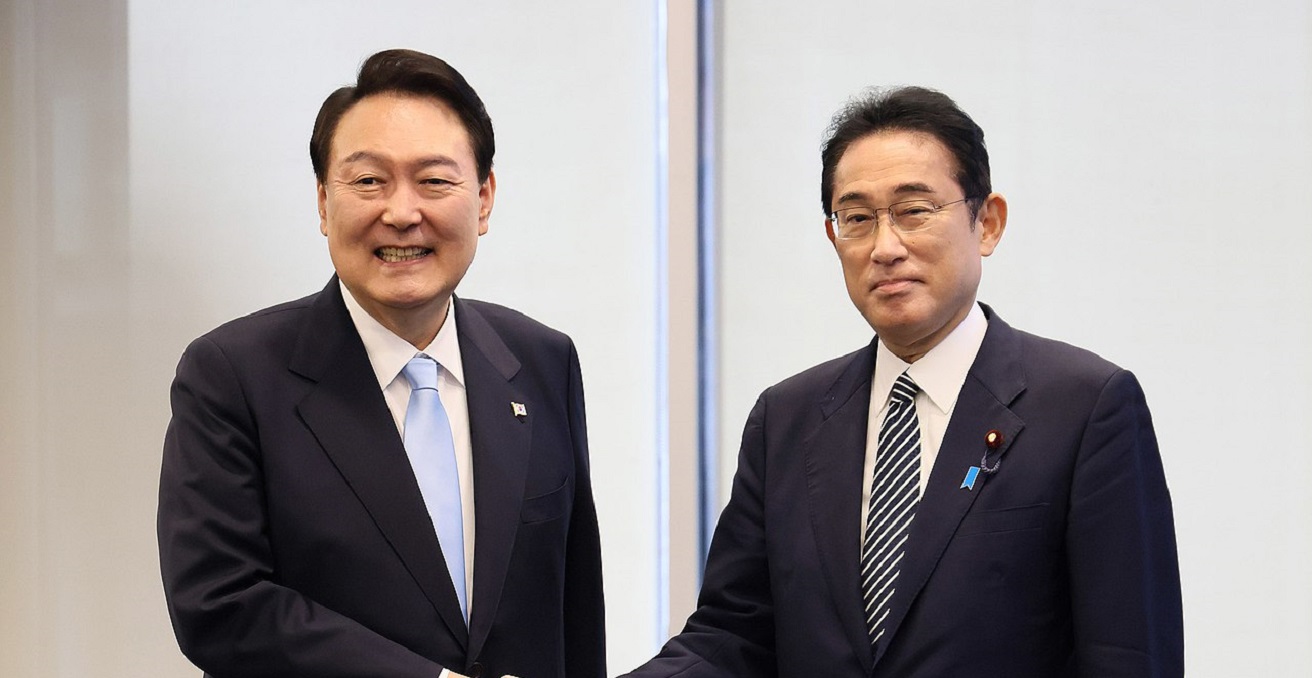

Recently, this situation has become more complicated. Externally, while North Korea continues to develop its nuclear arsenals, US-China strategic competition is heating up, to the extent that hostilities may erupt on Taiwan. What would be the role of South Korea in such an eventuality? Internally, South Korea continues to be deeply divided ideologically between the progressives and the conservatives. Between 2017-2022, the progressives controlled the presidency under Moon Jae-in. Moon’s pro-North Korea/China stance made South Korea “a weak link” in the US-led alliance system, while simultaneously bringing his country’s relations with Japan to their lowest point in recent memory. It was only with a razor-thin margin that Yoon Suk Yeol won the 2022 presidential election against his progressive opponent whose party continues to hold a majority in the parliament. Under President Yoon, Seoul has taken a more pro-Japan (and pro-US) posture, which was welcomed and reciprocated by Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. But President Yoon’s non-renewable term will end in 2027. How long will the current pro-Japan posture of South Korea last?

Enter the Camp David Agreement

In this context, the outcome of the Camp David agreement of 18 August 2023 between Prime Minister Kishida, President Yoon, and US President Joe Biden looms large. Put simply, this US initiative is a breakthrough as far as Japan is concerned. It has set up a continuing, institutional framework that provides Japan with a much firmer ground to achieve the aforementioned three conditions on South Korea. It is especially noteworthy that the agreement as an institutional mechanism will greatly help—although it will by no means guarantee—Japan to satisfy the elusive second and third conditions—a stable and Japan-friendly South Korea—in a way that was unimaginable a few years ago. There is a need to remain cautious, however. After all, coming to an agreement is not the same thing as executing it. Recall, for example, the ill-fated case of the “final and irreversible” Tokyo-Seoul agreement on comfort women (28 December 2015), which the Moon administration overturned in 2018—in fact, Kishida was Japan’s foreign minister who concluded this bilateral agreement, and Biden brokered it as the US vice president.

The Camp David agreement consists of three documents: (a) “The Spirit of Camp David: Joint Statement of Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States,” (b) “Camp David Principles,” and (c) “Commitment to Consult.” Furthermore, the White House produced “FACT SHEET: The Trilateral Leaders’ Summit at Camp David,” summarises the key points of the trilateral agreement.

What does it mean to characterise the Camp David agreement as an institutional framework? It refers to the fact that the three governments will consult and coordinate on an annual basis and at various levels of the government their policies toward common security and other challenges. Here, “various levels of the government” include the top leaders, key cabinet members (Foreign, Defense, and Commerce/Industry Ministers), and working-level officials (National Security Advisers and Assistant Secretaries). As such, this is a thick system composed of multiple layers for consultation and coordination (it does not require automatic military commitments à la the Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty). It is within this system that a wide range of topics were agreed to be discussed—wider than those directly related to the Korean peninsula and those directly related to security affairs.

The institutional framework of the Camp David agreement provides Japan with three functions, corresponding to the aforementioned three conditions of “threat-free South Korea.”

(a) Coordination (corresponding to the first condition)

The Camp David agreement works as a policy coordinating framework for a potential two-front war/crisis: across the Taiwan strait (China against the Japan-US alliance) and on the Korean peninsula (North Korea against the South Korea-US alliance). These two fronts may become linked and the three partners should be prepared in advance for such an eventuality. Take a Taiwan contingency, for example. Although South Korea may not directly involve itself in it, North Korea may opportunistically trigger a crisis against South Korea, for which the United Nations/US bases in Japan would have to react as well.

For Japan, the traditional role of South Korea as a buffer zone on the Korean peninsula remains the same, but it has become part of the broader, region-wide strategic competition between the United States and China, in which the geopolitical flashpoints—i.e., the 38th parallel on the Korean peninsula and the Taiwan Strait—are mutually connected. The Camp David agreement provides Japan with an excellent framework to deal with this reality.

(b) Binding (corresponding to the second condition)

The Camp David agreement works as a binding mechanism for future governments of the three partners in general, and a future South Korean government in particular, to keep uniting against the challenges posed by China and its allies. Although it is not perfect, it will serve as a “forceful reminder” that all future governments must honour the commitments. For Japan, this function of the agreement greatly helps to stabilise South Korea’s behaviour in its favour.

(c) Norm-building (corresponding to the third condition)

The Camp David agreement also works as a force of stabilisation in another way: by generating and consolidating cooperative norms in Japan-South Korea diplomatic relations. Seen from Tokyo, the agreement clarifies and cements the code of cooperative behaviour that Seoul should honour and follow vis-à-vis Tokyo.

Conclusion

The chemistry among the three leaders was just right, culminating in the historic achievement at the Camp David. For Japan, this was a breakthrough in coping with its perennial geopolitical imperative to keep Korea threat-free. True, it remains to be seen how robust, or fragile, the Camp David agreement turns out to be in the coming years. But we should give credit where credit’s due.

Tsuyoshi Kawasaki (kawasaki@sfu.ca) is Professor in Political Science at Simon Fraser University, Canada. A native of Japan and a specialist of international politics, he has widely published in both English and Japanese on such topics as Japanese foreign affairs, Canadian foreign policy toward Asia, and grand strategy.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.