Great Xi-pectations: Obsessing Over Other State Relations

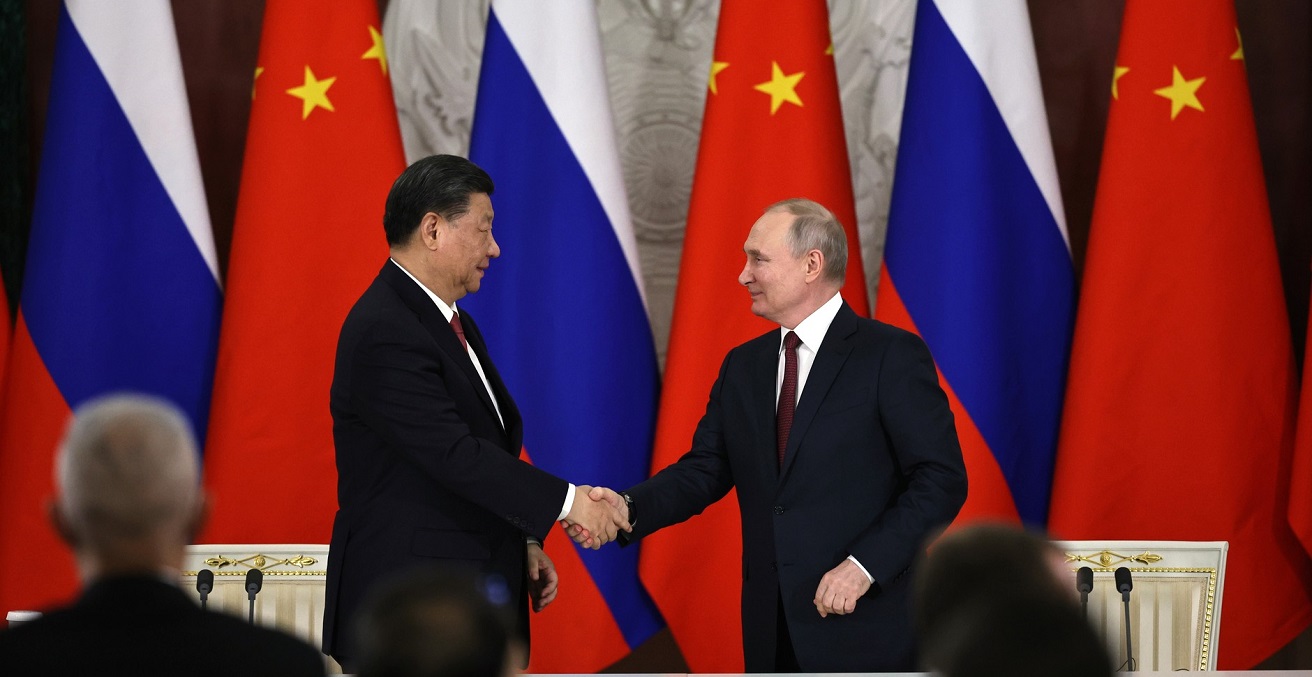

Framing the Sino-Russia “axis” narrative in terms of which power wears the pants is not all that helpful, nor is lamenting the end of the international world order as we know it. Yet Australia’s Xi-Putin Summit coverage did just that.

Xi Jinping wasn’t travelling to Moscow to promote European peace, nor tout China’s peacemaker potential. Beijing’s recent diplomatic boon facilitating talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia and China’s “Global Peace Plan” for Ukraine aside. Nonetheless, a cursory review of Australian media coverage of the Xi-Putin Summit indicates that watchers took the peace “bait.” Many are also challenged when it comes to definitions of and grasping the ins and outs of what makes an “ally.”

Coverage zeroed in on the growing power disparity between Moscow and Beijing, celebrating the thought of Vladimir Putin kowtowing to Xi. Some even lamented the complete subjugation of Moscow to Beijing. Yet the existing economic and strategic power disparity between the two states is a pre-existing condition, of which both are sharply aware. Dollars (or Yuan) don’t lie – China and Russia are long-term economic unequals. Indeed, arguing Moscow “failed” to secure a deal with Beijing over the new Power of Siberia-2 natural gas pipeline during talks overlooks the fact that the last Power of Siberia deal took 30-years to negotiate. Moscow might be under Beijing’s thumb, but China will need a relatively strong (and stable) Russia in its corner to endure strategic competition with Washington.

Plenty of ink was spilled on the Xi-Putin “bromance,” poring over joint statements on “Deepening the Russian-Chinese Comprehensive Partnership and Strategic Cooperation for a New Era” as well as the “Plan to Promote the Key Elements of Russian-Chinese Economic Cooperation until 2030.” Analysts and pundits alike cautioned the new developments of Sino-Russian state atomic energy projects – including an ominous sounding “Comprehensive Long-term Cooperation Programme on fast neutron reactors and closed nuclear fuel cycle development.” But Russia is already constructing nuclear power plants in China and has long been actively engaged in Beijing’s nuclear sector. Nuclear energy is merely another area of existing mutual interest for strategic cooperation. It is not about the West.

Indeed, missed by many was the fact that on the same day as greeting Xi, Putin keynoted the “Russia-Africa in a Multipolar World” parliamentary conference. Putin touted advances in the field of nuclear energy – noting Moscow is already building a nuclear power plant in Egypt. Many other African states are eyeing Russia’s total finance packages for nuclear energy systems. Furthermore, Angola is home to Russian satellite communication and television broadcasting systems. This is not about the West, nor is it about China. In Africa, the Sino-Russian partnership of strategic coordination does not neatly apply – for on this continent, they are strategic competitors.

Newly minted body language and table size “experts” have also overlooked the reality that Russia is not denying its junior role relative to Beijing. Instead, media coverage and expert analysis appeared to focus on the rather irrelevant question of who is the “alpha” in the relationship. If Moscow doesn’t seem particularly concerned with labelling its relationship with Beijing as anything more than a “comprehensive strategic partner of coordination,” then why does the West fixate on who has the upper hand? Arguments of whether Moscow is Beijing’s ally or resource appendage aside, it is not even evident if quantifying the relationship’s power dynamic is a useful application of energy (or time).

Worth consideration is our changing international system, and what needs to be done in Australia to bolster its position. Before ideological arguments are flung, as per Australia’s China “debate” more broadly (which serve ultimately to distract), it is important to unpack the collective avoidance of acknowledging that change in the international political system is enduring. It is worth pointing out we easily accept that the centre of economic power has been moving East (back) to Asia for some decades now. But acknowledging the other variables of power that are also reorienting to Asia appears to be a bridge too far to cross.

The Xi-Putin summit is just the most recent example in a long line of undercurrents throughout the globe which underscore that a new global architecture is perhaps much further along than those in the West would like to comfortably admit. Packed with new centres of power (however one wants to quantify it), this architecture will feature Russia and China in some way – and whether Moscow is under the pump and Beijing holds the cards should not be the focus. There are much more pertinent questions to ask right now: how does Australia deliver on an independent foreign policy in a region that is actively orientating away from a Western orbit? What are the costs in transitioning to this new order, and what is the Australian public willing (and ready) to absorb?

The least sexy security consideration – which desperately needs attention – is not answering questions as to which autocrat is the bigger autocrat. National coverage should be focusing on Australia’s position, policy, and potential in response to an evident shifting international power balance. A national security strategy might be an apt place to start.

Dr Elizabeth Buchanan is Head of Navy Research at the Sea Power Centre. She is a nonresident fellow of the Modern War Institute at West Point. All views are her own. @BuchananLiz

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.