Geopolitical Rivalry as Hypermasculinity Contests: The Case of Australia-Philippines Strategic Partnership

The Australian-Filipino strategic partnership is contrived in hypermasculine terms. This has potentially catastrophic consequences for the region and the planet.

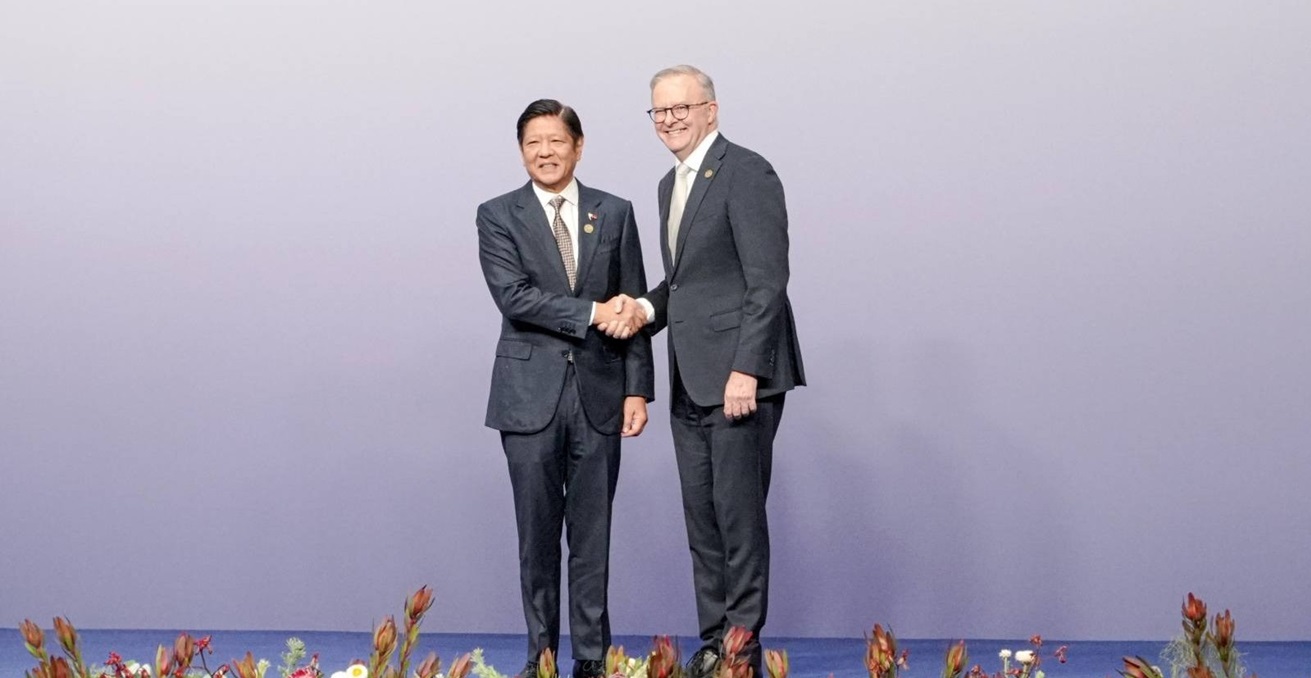

“We will not yield.” This was what Philippine President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. declared as he addressed a joint sitting of the Australian Parliament last week. Marcos vowed that “not one square inch of sovereign territory will be taken by any foreign power” as the Philippines continues to be on the frontlines of regional threats to peace and stability. Last week, Australia-Philippine bilateral relations marked a historic step up as part of ongoing efforts to upgrade the strategic partnership between the two countries. This speech represented a first for a Philippine state leader. Another state leader received the same rare honour a couple of weeks prior when James Marape, prime minister of Papua New Guinea, became the first Pacific leader to address a joint sitting of parliament. These historic visits – side by side – reveal Australia’s strategy to position itself as a regional power by fortifying security alliances across Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

The opportunity to strengthen partnerships between Australia and the Philippines was made possible precisely because of the marked shift in foreign policy approach under Marcos Jr compared to his predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte. The current president has been significantly more assertive of Philippine sovereignty over the contested areas of the West Philippine, or South China, Sea. This is exemplified by the resumption of the security alliance with the US, and bilateral agreements on maritime cooperation most recently with Vietnam and Australia respectively.

If we are to believe pronouncements by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, opposition leader Peter Dutton, and President Marcos last week, efforts to strengthen the strategic partnership are “natural” courses of action given the shared history and future of the two nations. Indeed, all three speeches asserted that the basis of mutual friendship is rooted in DNA as both peoples trace lineages back to ancient seafaring Asian and Pacific ancestors, and therefore have destinies that are “irrevocably linked.” Filipinos and Australians have fought side-by-side before – from Bataan and Corregidor during WWII to Korea in 1951 and in Timor-Leste in 1999. The alliance has therefore stood the test of time and in the face of actual conflicts. Moreover, these historical bonds are bolstered by the cultural complementarity between “Bayanihan” (mutual assistance) and “Mateship” (equal partnership). This was evident when Australia came to the aid of the Philippines at a time of great need, in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in 2013.

The partnership is also a “necessity” given “uncertain times” shaped by “emboldened autocrats and belligerent regimes,” to use Dutton’s words. As island nations, protecting freedom of navigation is inherent to the national interests of both the Philippines and Australia. Thus, the two ought to take on the mantle as middle powers of protecting a rules-based order in the region, and the world more broadly.

Feminist scholarship in peace and security, however, would caution against naturalising discourses that frame geopolitical rivalry and strategic partnerships as “normal” and “necessary” stances. Rather, these discourses are steeped in constructed and contested ideas of masculinity and femininity. For instance, state hypermasculinity in security and economic domains reproduce a world where no one is truly safe from the threat of war. Hypermasculinity has been traditionally understood as a threat reaction or backlash wherein states are configured to inflate or exaggerate the securitisation of borders and sovereignty claims. Hypermasculinity of one state triggers hypermasculine, or militarised, responses from another, thereby fuelling recursive bouts of violence and conflict in the name of national interest. We can, therefore, interpret strategic partnerships between Australia and the Philippines as “mirror strategies” in response to the geopolitical rivalry between the US and China over Asia and the Pacific. What we are witnessing is hypermasculine envy and competition over who has more power and dominion to control.

State hypermasculinity demands hyperfemininity from society which means utmost obedience and submission to national security imperatives. Consequently, this stance is inimical to public deliberation and may involve collusions to sideline thorny issues that might derail or distract from “what really matters.” Indeed, despite references to friendship and common bonds, last week’s event did not include any reference to the rule of law and protection of human rights domestically. The response instead has been erasure, as seen in the removal of Greens Senator Janet Rice who raised a placard reading: “Stop the human rights abuses.” Yet, even the closest of friends must be able to have difficult conversations in order to have a meaningful friendship. This suggests that, paradoxically, hypermasculine stances are very fragile and require constant orchestration of rituals and rhetoric.

Hypermasculinity as a logic or “cognitive shortcut” can be examined in relation to how the state allocates resources and responsibilities during peace time, how it interprets and frames crises, and consequently the range of expertise and courses of action it deems appropriate. The danger of hypermasculine competition is that it can stratify and separate what are otherwise interrelated security issues. Health, education, and environmental sustainability are feminised, for these are considered secondary or less significant compared to state survival.

For example, the region has seen a continuous rise in military spending, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Both Albanese and Marcos rightly pointed out that climate change is a major security threat that needs to be addressed. Yet, militaries are major consumers of fuel and account for approximately 5.5 percent of global carbon emissions. Unsurprisingly, the combined carbon footprint in and of our region constitutes the highest share of the global total. All this militarising is leading us to a planetary crisis.

It is important to ask, therefore, what the wider cost of building the Australian and Philippine mateship is? Who benefits from all the strategic partnering? Asking these questions and paying attention to gender and broader perspectives on security reveal uncomfortable truths. First, there is nothing “natural” or normal about the specific forms security cooperations take – these are outcomes of political decision making. Second, challenging the naturalisation of geopolitical rivalry invites us to critically reflect on what counts as necessary for a good life, and how we might collectively pursue it. While we will continue to be inured to the inevitability of war and securitisation, another world is (still) possible.

Maria Tanyag is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations, and the Deputy Director for the Philippines Institute, at the Australia National University.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.