Five Eyes and the Perils of an Asymmetric Alliance

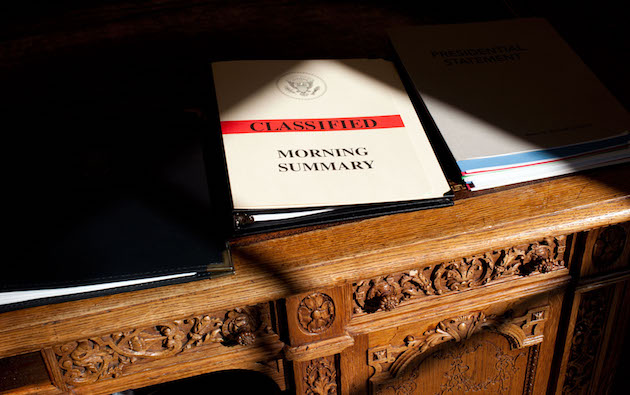

Five Eyes is the oldest and most prominent intelligence alliance in the world. But does Australia’s membership in the alliance expose it to undue influence by US interests?

The US has the largest and most expensive intelligence apparatus in the world, indeed in the history of humankind. It is because of this, critics charge, that Washington dominates intelligence cooperation among allies due to the sheer scale of its capabilities. The evident asymmetry of the relationship between the US and its allies, according to this perspective, produces outcomes that are inimical to the interests of smaller countries, which have little choice but to accept the consequences of the power imbalance.

However, just as smaller states often seek out security alliances with major powers, they also covet the benefits that flow from intimate intelligence-sharing arrangements with more powerful states. As with alliances, junior partners that have intelligence-sharing arrangements with more powerful states are willing to sacrifice some autonomy in return for pay-offs in other areas.

Understanding the dynamics

Alliances are much more than transactional arrangements. To be sure, alliances are formed because of perceived threats from other states, but alliances can endure when threats either change in scope or dissipate altogether. NATO’s endurance after the Cold War is the most prominent case in point.

Despite Washington’s periodically stated concerns over the tendency of allies to free-ride on security guarantees, the US places great store in its alliances as evidence of its global reach, appeal and strategic influence. For junior allies, a security alliance with a major power provides more obvious benefits including the prospect (if not necessarily the guarantee) of military protection in crises, preferential access to high-end military equipment and joint training, and a sense of reassurance that promotes confidence in the execution of foreign policy and international engagement more generally.

Countries expect certain pay-offs from alliances and the expectation is that alliance relationships should yield roughly commensurate results. By allying with a major power, junior parties will expose themselves to a situation where they may be expected to support the major-power ally even when these policies are at odds with the junior ally’s interests.

The Five Eyes

Accusations persist that the network is an exclusive club designed to reinforce the global influence of the Anglosphere, and that its highly secretive nature is an anachronism in a world where the general public’s call for accountability and transparency is a strong theme permeating the discourse of globalisation. The apparent blurring of foreign and domestic intelligence since 9/11, which was dramatically underscored by the Wikileaks and Snowden disclosures, has triggered unease about the scope for authorised and unauthorised electronic espionage directed by intelligence agencies against their own citizens and those of their allies.

The Five Eyes network is the world’s oldest formalised intelligence network and has its origins in the significant expansion of Allied intelligence cooperation and exchange during World War II. The network was founded with the conclusion of the top-secret UKUSA Agreement of 1947 that formally codified the division of spheres of responsibility for signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection between the ‘First Party’ (the United States) and the ‘Second Parties’ (Australia, Britain, Canada and New Zealand). The countries established detailed cooperation activities during the Cold War in areas as diverse as ocean surveillance, covert action, human intelligence collection and counterintelligence

In the software domain, one of the most salient features of Five Eyes has been the so-called Echelon program, which since the 1960s has involved the interception from civilian satellites of communications based on keywords submitted by each Five Eyes member country. Furthermore, the contemporary global reach of Five Eyes is exemplified by the formal burden-sharing responsibilities among its members whereby regions of the globe are divided amongst the members.

Another key feature of the Five Eyes alliance is the sharing of intelligence with so-called ‘Third Party’ countries such as Denmark, France, Singapore and South Korea. Yet, despite this, the Snowden disclosures also revealed that the Five Eyes partners have, in turn, directly targeted many of these.

Australia and the Five Eyes

Australia’s initial engagement in the Five Eyes network was essentially a product of its close relationship with Britain and its intimate wartime intelligence collaboration with the US. The Five Eyes alliance has become more important to Australia over time.

The post-9/11 homeland security agenda has accelerated information-sharing regarding counter-terrorism, cybercrime and encryption, among other areas. In addition to jointly used facilities like Pine Gap, intelligence officers are also embedded in counterpart UKUSA agencies.

Like Canada and New Zealand, Australia’s involvement in the Five Eyes alliance is unambiguously as a junior partner to Washington. Britain’s established global intelligence capabilities and historical role in Europe make it more of a senior partner.

Australian governments rarely comment on what they regard as the primary value of Five Eyes, but when they do, two key themes are apparent. The first is a classic refrain from junior alliance partners that if they did not have access to the capabilities provided by larger powers, they would have to outlay more on safeguarding their security. The second theme evident in public comments by serving and former Australian officials is that the density of interactions in the multilateral Five Eyes context promotes deeper trust at the bilateral level with members.

It has been estimated that the two-way intelligence flow between Australia and the US is roughly 90 per cent in Australia’s favour, with Canberra providing niche contributions overwhelmingly in relation to Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. Echoing the alliance studies literature, however, an obvious danger for junior partners is that the asymmetry inherent in the Five Eyes arrangement exposes them to potential manipulation and control by the dominant major partner. The landmark Hope Royal Commission noted that there is a danger that some of the information Australia is given access to will be deceptive or misleading and operational cooperation may entail some loss of operational independence.

Typically, critics of Australia’s involvement in the Five Eyes network and the bilateral intelligence relationship with the US allege that Australia is exposed to increased physical risk, by having high-value intelligence installations on its soil, and increased political risk, stemming from what is portrayed as over-reliance on US intelligence. Since the 1980s, successive Australian governments have conceded that the joint facilities expose Australia as a likely nuclear target, but have also emphasised that this is outweighed by the contribution these bases make to national security.

The question of political risk resulting from dependence on US intelligence is harder to address because it is not something that can be easily gauged. Whether Washington leverages its capabilities to exert dominance over its allies in commitments they would otherwise avoid remains an open question. However, the perception was encouraged by the Iraq War experience, where almost all raw intelligence used to support the case was sourced from American and British collectors.

Yet states make foreign policy according to a wide range of factors; it is the assessments that are the crucial variable. Canada and New Zealand both had access to the same intelligence sources as Australia but chose not to participate in Iraq. In the area of intelligence analysis, Australian assessments, especially of Asian developments, at times differ sharply from those of the US.

While the implied risks of entrapment may be minimal for Australia as a junior Five Eyes partner, another prominent alliance dynamic—intra-alliance bargaining—has been a feature of the relationship. There is substantial evidence US provided extended intelligence support in the build-up to the East Timor mission in 1999. More recently, intra-alliance bargaining has been evident in Australia’s reported endeavours to upgrade the intelligence-exchange relationship in the counter-terrorism domain.

The Five Eyes intelligence network is rarely, if ever, analysed in terms of it being an alliance. In many respects, the Five Eyes network is the world’s most enduring and robust alliance, eclipsing even NATO in terms of high-level information exchange among members.

Andrew O’Neil is professor of political science and head of the School of Government and International Relations at Griffith University. He is the former editor-in-chief of the Australian Journal of international Affairs and the author of several books, the most recent of which is ‘Middle Powers and the Rise of China‘ .

This article is an edited extract from a paper published in the Australian Journal of International Affairs on 6 July 2017. It may be accessed in its unabridged form here.