Evolving Policy: Malaysian Diplomacy in the South China Sea

Malaysia has pragmatically optimised diplomatic and legal instruments as the principal forms of statecraft to advance its interests. Diplomacy and selective deference are central to preserving sovereignty and keeping bilateral ties, while legal means have served to protect Malaysia’s interests through quiet, indirect defiance.

These instruments, used together, have enabled Malaysia, a smaller and militarily weaker state, to deepen its light-hedging, while pursuing oil and gas exploration activities in its claimed areas (quiet developmental actions). Light hedging is essentially a non-confrontational, low profile, and seemingly contradictory approach through which a weaker state hopes to defend its maritime-territorial integrity and safeguard economic interests while offsetting multiple risks in an increasingly uncertain external environment.

Diplomacy, via both bilateral and multilateral channels, has been used by the Malaysian government to manage maritime disputes. Bilaterally, Malaysia has conducted negotiations with Brunei, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, and Vietnam, to delimit their continental shelf and maritime boundaries. Malaysia reached agreement with Brunei in 2009 to delimit their overlapping boundaries.

Malaysia has also embraced multilateral diplomacy as a means to promote its interests. It has long advocated the realisation of the ASEAN-China Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (SCS). It has also promoted ASEAN’s commitment to a “common ASEAN position” on engaging China on the SCS issue, in addition to assuming a more central role in brokering a peaceful settlement of the dispute. Malaysia has proactively engaged ASEAN member-states both privately and publicly “to narrow differences,” while seeking to “forge a united front against coercion in the wake of rising tension in the SCS,” with China implicitly the target of such initiatives.

However, there have been shortfalls on multiple fronts. ASEAN member states lack the political will to confront China, as there is division between non-claimant and claimant-states, which has been accentuated by Beijing’s “divide-and-rule” strategy, as well as “carrot-and-stick” approach. Moreover, ASEAN claimant-states are “neither friends nor foes” when it comes to defending their respective SCS interests. On one hand, they share a common concern in China, due to their perception of the Chinese as being the most assertive actor in the SCS and their own asymmetric power relations vis-a-vis Beijing, when dealing with China as individual states. On the other, competing maritime jurisdiction claims in the SCS remain a source of distrust and tension, with Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia still deadlocked on issues of sovereignty and territorial rights.

Nonetheless, Malaysia remains committed to diplomacy as the means to secure its SCS interests. In addition to leveraging ASEAN-based multilateralism whenever possible, the Malaysian government has continued to pursue bilateral diplomatic channels, including its much touted “quiet diplomacy” of privately communicating with claimant-states like China, whenever incidents affecting Malaysian interests occur in the SCS. This includes issuing numerous “unpublicised” diplomatic notes of protest, which “help keep Malaysia’s claim alive, and serve as a record of official action undertaken to assert its claim,” while censoring public visibility for the sake of “preventing inflammation of incidents” such as the Chinese intrusions and ceaseless presence near the Luconia Breakers.

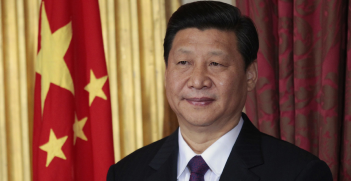

Another more recent example was Malaysia’s decision to agree with China’s suggestion in September 2019 to set up a bilateral consultative mechanism to promote dialogue and cooperation regarding SCS issues. Indeed, Beijing has appreciated and made positive comments regarding Putrajaya’s relatively “milder” approach, an acknowledgement of Malaysia’s selective deference to China. For instance, in late 2014, President Xi Jinping praised Malaysia’s “quiet diplomacy” in tackling SCS problems, as compared to Hanoi’s confrontational and Manila’s international arbitration approaches.

Despite changes in the contested SCS and domestic politics, quiet diplomacy has thus far remained Malaysia’s primary and preferred approach in managing the SCS dispute. Yet, observers have noted that Malaysia’s SCS policy has evolved. Specifically, Malaysia’s past diplomatic prudence has been characterised by periodic media criticisms and reproach of the persistent Chinese challenges to Malaysia’s maritime-territorial sovereignty in the SCS. In addition to lodging regular diplomatic notes to protest, manage, and resolve the repeated intrusions of Malaysian waters, Wisma Putra’s uncharacteristic summoning of the Chinese ambassador in response to the 2016 encroachment of more than a hundred Chinese fishing vessels in the vicinity of South Luconia Breakers, as well as media exposure and even calls for a renaming of Malaysia’s portion of the SCS, were viewed as telling signs of a possible Malaysian pushback against China in the SCS.

These indications led to premature speculations of a possible major shift in Malaysia’s China policy following the advent of Mahathir’s Pakatan Harapan (PH) government, in power from May 2018 to February 2020. In contrast to the earlier views, the tone of Sino-Malaysian relations has returned to normal, albeit recalibrated to reflect the PH government’s goal of facilitating a more equidistant relationship with China. The recalibration of the Malaysian government’s China policy is manifested in Putrajaya’s “dual-track” approach that decouples Beijing’s SCS challenges from the more positive dimensions of Sino-Malaysian relations. In an interview given after PH’s electoral victory in 2018, Mahathir recognised the economic potential of China’s BRI, while chiding Chinese naval intimidation and bellicosity in the SCS. Likewise, during the Belt and Road Forum on International Cooperation in April 2019, Mahathir’s reiteration of the need to ensure the SCS remains free, open, and safe also exemplifies the “middle path” that Malaysia treads in the context of growing Sino-US strategic competition.

Malaysia’s quiet diplomacy is rooted not only in external power asymmetry but also internal political needs. China has become more economically significant to Malaysia’s ruling elite in the past few years. China has been Malaysia’s largest trading partner for eleven consecutive years, while Chinese tourists and investments have flooded the Malaysian market during the last five years. Even without considering the multi-billion dollar, BRI-related, Sino-Malaysian mega projects, the magnitude of Malaysian and Chinese bilateral economic involvement and deepening interdependence have made China increasingly indispensable to Malaysia’s political elites. Given these multifaceted partnerships and the underlying economic interests, both Malaysia and China have chosen to downplay the SCS issue, cautiously managing the dispute and seeing it as “only one–albeit significant–element of its bilateral relationship with China.”

Yew Meng LAI is Associate Professor of Politics and International Relations and Dean of the Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning (CPKLL), Universiti Malaysia Sabah. He is also a research fellow at the varsity’s Small Island Research Centre. Lai obtained his Master’s in International Political Economy and Ph.D. in Politics from the University of Warwick. He was formerly attached to the Japan Institute of International Affairs as a Visiting Research Fellow (2003–2004). Lai’s research interests include: Japanese/Chinese foreign policy, Sino-Japanese relations, East Asian security, Malaysian politics and foreign policy, and Indonesia-Malaysia relations.

Cheng-Chwee KUIK is Associate Professor and Head of the Centre for Asian Studies at the National University of Malaysia (UKM)’s Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS). Dr. Kuik’s research concentrates on weaker states’ foreign policy behaviour, regional multilateralism, East Asian security, China-ASEAN relations, and Malaysia’s external policy. He holds an M.Litt. from the University of St. Andrews, and a PhD from the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

This article is an extract from Lai and Kuik’s article in the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled “Structural sources of Malaysia’s South China Sea policy: power uncertainties and small-state hedging.” It is republished with permission.