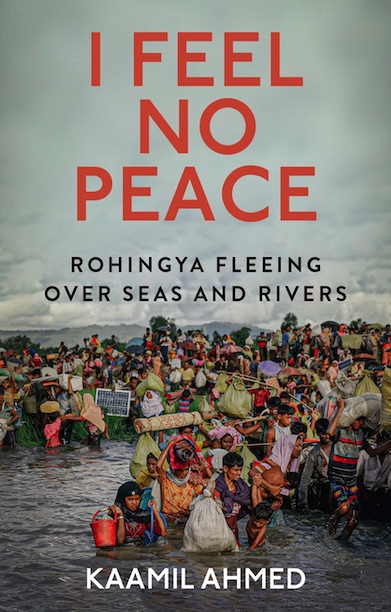

Book Review: I Feel No Peace: Rohingya Fleeing Over Seas and Rivers

Kaamil Ahmed’s documentation of the Rohingya’s plight details their trauma, death, and despair. The book’s telling of their human longing for peace and a better life should enjoy a wide readership.

Kaamil Ahmed has covered the plight of the Rohingya for the Guardian’s global development desk, and this book relies on many of the trips and interviews he conducted in the course of this work. The longform allows him to delve deeper and present a more nuanced assemblage of stories that follows a range of Rohingya from Myanmar to the notorious refugee camps in Bangladesh and beyond, to Malaysia where many Rohingya now work and live.

Throughout the book, the issue of Rohingya claims to a history and place in Myanmar come to the fore. Denied education, citizenship, and representation by the state means that few can navigate the ever-changing requirements to belong to Myanmar – by design. Few ever had the documentation required to stay ahead of and within state definitions of belonging to Myanmar. Ahmed recounts one powerful story of only one such family with all the necessary documents who ultimately still are excluded from belonging to and in Myanmar. This means no amount of documentation would ever suffice, when the state with its extensive bureaucratic and violent means is so intent on removing Rohingya from Myanmar.

Today, most Rohingya have, at best, some form of refugee identification, usually from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Many Rohingya left their documents in Myanmar, intent on reclaiming them when it was safe to return or tossed them in fear of forced repatriation to an unsafe homeland. Thus, they are trapped in a limbo where their identity is just where the Myanmar state wants it to be – unresolved and undetermined. It means they cannot travel legally across borders, making them reliant on unscrupulous human smugglers and traffickers plying their trade in the Andaman Sea. And even if they manage to escape, it leaves them at the mercy of the people and places they have scrambled to claim asylum, be that Bangladesh, Malaysia, or Indonesia.

The book documents in detail the prolonged and incessant back and forth between the Bangladeshi government and Myanmar authorities Rohingya refugees have been subjected to, without a say. They have been pawns in political, regional, and domestic moves that have subjected them to unimaginable suffering, pain, and loss. Ahmed exposes the murky relationships between the UNHCR, the Bangladesh and Myanmar governments, and security forces that perpetuate an objectification and othering of Rohingya, for example when discussing repatriation:

This suited Geneva, who wanted their local staff to push ahead with the process. At one meeting at headquarters, its approach to Rohingya voices was made clear by a senior official: “The Rohingyas are primitive people. At the end of the day, they will go where they are told to go.”

Ahmed puts these quotes in context when he recounts the way the UNHCR has, in the past, stood by when Bangladesh cut food rations in the 1970s and thousands of Rohingya died or when the recent repatriation discussions between the UNHCR, Bangladesh, and Myanmar were held without Rohingya representatives and resulted in an utter lack of information sharing with those affected.

Rohinyga refugees have had to accept the realisation that even regional Muslim majority states like Bangladesh are no longer a sanctuary. As one of Ahmed’s interlocutors remarked: Bangladesh’s “job is to control the Rohingya, their job is to destroy the Rohingya, their job is to force them to go back to Myanmar.” It is inherently difficult to know who to trust in such an environment, especially when Rohingya have been betrayed so many times by the states around them, by people taking advantage of them, and by their own trying to get ahead at the expense of each other. Another backdrop to the book is the Gambia genocide case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against Myanmar, which has proven a pyrrhic victory of sorts, where Myanmar, and above all its respondent in court, Aung San Suu Kyi, were discredited. The ICJ case has changed nothing on the ground and certainly not for the Rohingya.

As an academic reviewing this book, I would have liked more references or citations that demonstrate where evidence and knowledge is derived from, especially when it is murkily constructed, such as when Ahmed recounts a story about an unnamed American researcher and a report readers are not privy to:

To prove it, they invited an American researcher who was writing a report about the process for the US Congress. Their plan backfired. The researcher witnessed everyone bursting into tears when they were told where the boats were going.

Sometimes the language Ahmed uses mimics the media’s framing of refugees as excess water seeking to find its way to the sea. He speaks of escape valves, trickles of refugees, and people flooding into Bangladesh. These imageries depict Rohingya as a permeable force seeking its way to another existence via the literal water of the Andaman Sea where again they face violence and the depravities of man in the form of traffickers sucking the last vestiges of their lifeblood in transit. This kind of imagery may be counterproductive to the humanising effect Ahmed’s narratives have.

His careful retelling of trauma, death, and despair as well as survival and what it takes to survive are brought to light in excruciating detail and thus it becomes all the more difficult to imagine how the hopeful vignettes of Rohingya, who do not give up and seek to unite, forgive and move beyond the horrors they have endured. But they are and this book does an excellent job in letting them rise above the refugee victimhood discourse that sees refugees as passive objects in global crises, and the hero-worshipping discourse of the few particular refugee leaders profiled as superhumans. Ahmed’s book is an example of the cumulative effect of stories about people being more than the sum of its parts – together they paint a complex picture of a group of people who have endured unimaginable trauma and continue to forge new lives in often desperate circumstances. This book humanises Rohingya, their history and place within it, and their demands for a better future. Hopefully it receives a wide readership far beyond academia and, through its empathetic storytelling, connects its readers with the human aspirations of Rohingya for a better life and peace in their lifetime.

This is a review of Kaamil Ahmed’s I Feel No Peace: Rohingya Fleeing Over Seas and Rivers (Hurst Publishers, 2023). ISBN: 1787389316

Gerhard Hoffstaedter is an associate professor in the School of Social Science at the University of Queensland.

This review is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.