Arresting Pakistan’s Imran Khan Will Not Fix Things

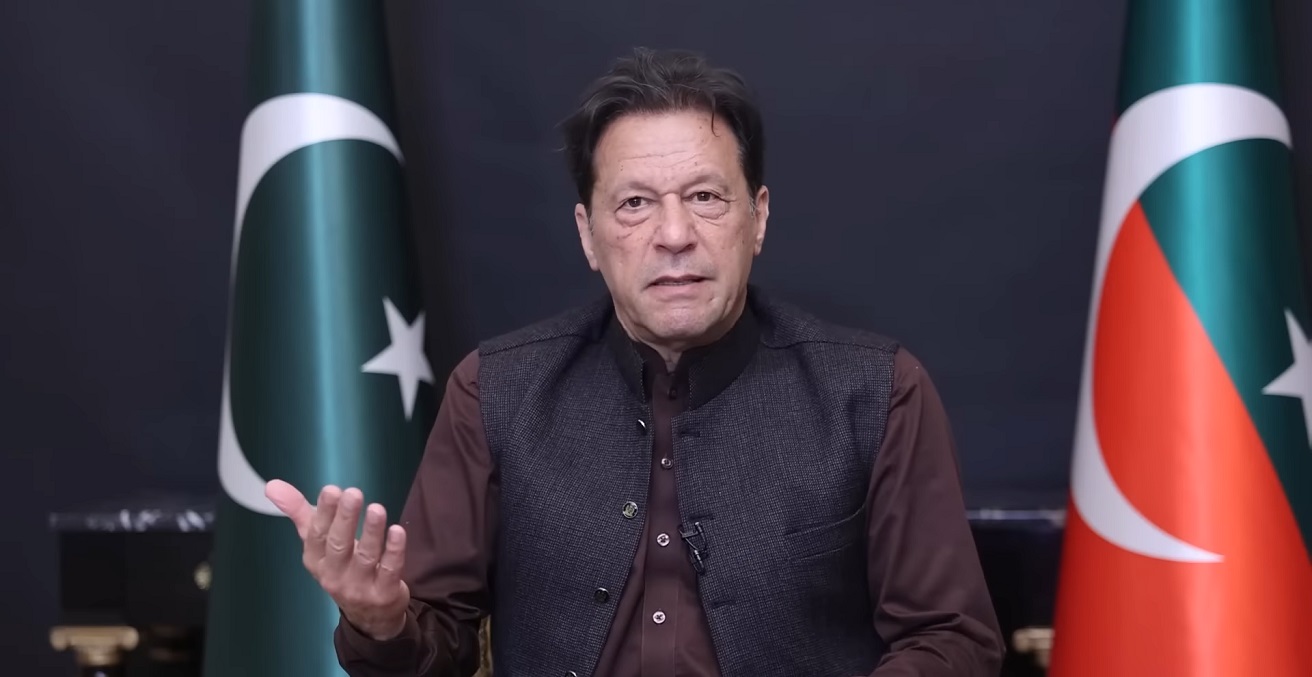

Last week’s arrest of former prime minister Imran Khan on corruption charges comes at a time when the country is already suffering from deep structural governance problems. The forthcoming national elections without Khan will make matters worse.

On 5 August an Islamabad court judge declared Imran Khan guilty of “corrupt practices” and sentenced him to three years in jail. The judge, who is known for his particular dislike of the 70-year-old former prime minister, accused Khan of misusing his nearly four year-long premiership to buy and sell gifts in state possession that were received during visits abroad worth almost half a million US dollars. Khan, who was not present in the court, was also fined ₹100,000 rupees (US$355).

Khan was hauled from his home in Lahore by a large contingent of policemen and eventually transferred to Rawalpindi’s Central Prison Adiala, relatively close to his former residence in Islamabad. His lawyers are appealing the sentence.

According to the constitution, this sentence automatically disqualifies him from running for public office for the next five years. And this is precisely what the military and the governing coalition wanted: bar Imran Khan from participating in the forthcoming national election.

The Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA) expressed “serious reservations to the legality” of the verdict. The SCBA added that “the historical trend of disqualifications and ban of popular political leaders by the judiciary is against the principles of democracy and fair trial as enshrined under the constitution.” And this is indeed the problem with the removal of the most popular politician from the electoral cycle: it effectively rigs the forthcoming elections in favour of the constituent parts of the incumbent coalition government, the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM).

The political players

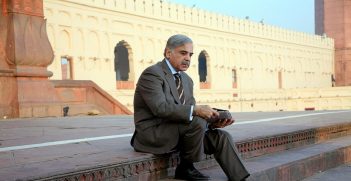

The PDM is a motley group of 11 parties whose only common glue is their loathing of Imran Khan. But now that Khan has been removed from the political equation, one can expect the PDM to disintegrate relatively quickly. The two major parties in the PDM are the Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Their hatred of each other is only slightly less than their hatred of their common foe, Imran Khan. The present prime minister, Shehbaz Sharif, is the younger brother of the former three-time prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, who is residing in London. Nawaz, who is probably the wealthiest man in Pakistan, is the leader of the PML-N and he calls the shots, as much as a civilian can in Pakistan’s peculiar military-civilian hybrid political system. He has corruption charges hanging over him in Pakistan, hence his exile in London. There are rumours that these judicial charges could be lifted, and he could come back to run in the forthcoming elections. Although not as popular as Imran, Nawaz nevertheless has a significant following in Punjab, the country’s largest province.

The second most important party in the PDM, the PPP, is led by Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari—son of the late PM Benazir Bhutto (killed by terrorists in 2007) and grandson of the late PM Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto (executed by Gen. Zia-ul-Haq in 1979). While the PPP’s base is Sindh province, today the PPP is a mere shadow of its former self. Still, he sees himself as a future prime minister of Pakistan.

Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI)(Pakistan Movement for Justice), which was founded in 1996, was the largest party in 2018, when Imran Khan formed government with the support of some minor parties. However, today the PTI has to all intents and purposes been gutted. About a year following his ouster from office in a parliamentary vote of no confidence in April 2022, Imran Khan was arrested on corruption charges. This led to a violent national reaction by PTI followers. With the acquiescence of the PDM government, the military responded ruthlessly and mercilessly against anyone connected to the PTI. Ten thousand PTI party members and followers were arrested and locked up. Most PTI leaders were either forced to resign under duress, tortured or joined the military-approved Istehkam-i-Pakistan (Pakistan Stability Party), a political party with little credibility. The rapid collapse of PTI is no surprise given that many of its leaders were defectors from the PML – N and the PPP. Put differently, their loyalty to Imran was shallow and was only going to last as long as their parliamentary seats were secure.

Election Time

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif plans to dissolve parliament on 9 August. According to the constitution the federal election must be held within 90 days. However, the actual date for the election will most likely be delayed four months or more to early next year, probably February 2024, because the 2023 digital census was recently approved by the government, and constitutionally this means that fresh electoral delimitations will need to be approved before elections can be held. According to the latest census, Pakistan’s population has increased to 241.49 million, almost 35 million more people since the last census six years ago.

Regardless of when national elections are eventually held, polls without Imran Khan will be tantamount to rigging the elections. Whether one agrees with his politics or not, Imran Khan remains by far the most popular politician in Pakistan. He has mobilised the population, particularly the youth of the country, to stand up against the military and the political establishment. Locking up Imran Khan will not bring stability to the country. On the contrary, it will enflame an already difficult political situation. I suspect many will boycott the elections, making the result meaningless. Most would reject the fixed outcome.

This would be a bad outcome for a country faced with a myriad of problems, particularly on the security and economic fronts. There’s been a significant increase in terrorist attacks from Afghanistan-based terrorists, particularly since the Taliban took over in Kabul in August 2021. And on the economic front, Pakistan regularly gets loans (not grants) from China, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia to tie the country over to avoid default on its repayments. But these only kick the can down the street without addressing the fundamental long-term economic issues facing the country.

Locking up Imran Khan is clearly not the solution.

Dr Claude Rakisits is an Honorary Associate Professor in the Department of International Relations at the ANU and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Brussels-based Centre for Security, Defence and Strategy at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.