Uganda’s Presidential Election: Voting for an Autocrat

Uganda’s presidential elections on 18 February are littered with controversy and intimidation – including the arrest of opposition leader Dr Kizza Besigye during the campaign – revealing all of the hybrid democratic-authoritarian paradoxes of the Museveni regime.

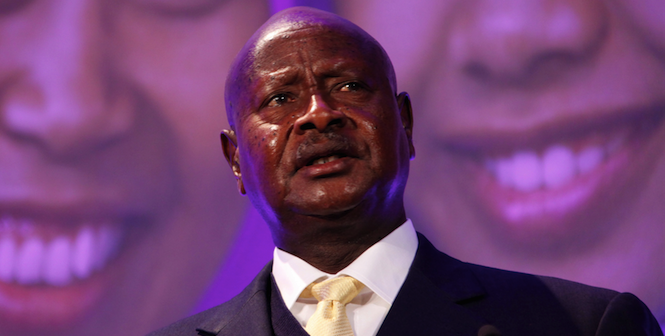

Uganda’s incumbent president, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, has juggled many public personas in his three decades in power. Since leading his guerrilla forces to Kampala in 1986, his most impressive flexibility has been his capacity to present two concurrent faces: one is that of the democratic reformer, the other is of the fearsome military ruler.

The former is the saviour of Uganda’s post-colonial collapse under presidents Milton Obote and Idi Amin, patron of democracy, and emancipator of woman and ethnic and religious minorities. These labels are not groundless, as Ugandans have long memories of the turmoil that preceded Museveni and remain impressed by the breadth of his early reforms.

The other face, however, is of the General who won power through a gruelling civil war in the 1980s and is entitled to enjoy it as long as he sees fit. This is the Museveni that dons military fatigues to threaten judges against anti-regime rulings, who repeatedly characterises rivals as security threats that he will ‘crush’, and who famously couches his extra-democratic right to hold power in folksy, bucolic metaphors about hunters keeping their prey.

With such a contradiction, election season in Uganda, which culminates with the Presidential and Parliamentary vote on February 18, reveals all of the hybrid democratic-authoritarian paradoxes of the Museveni regime. The rural south, where most voters live, has remained extremely loyal to the president in his previous four elections. Here, voters praise the peace that his government has brought, while simultaneously expecting him to go back to war to overthrow any successor that might defeat him at the ballot box. They vote for him in the large numbers recorded by the Electoral Commission, but do so in a highly intimidating environment where they are constantly reminded of the coercive capacity of the General, should he be upset.

Intimidation

State intimidation reached its peak in Museveni’s first two re-elections in 2001 and 2006, (he was first elected in 1996 after a ten year interim period) but remains a factor in the 2016 election season. Both key opposition candidates – perennial rival Dr Kizza Besigye and recently defecting Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi – have been arrested and harassed by the police. The latter’s head of security Christopher Aine disappeared in December and has yet to be found. At one incident in Ntungamo, youths from Museveni’s party, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), stormed Mbabazi’s rally and assaulted his supporters. When Besigye decided to make an unscheduled stop in a refugee camp near the Kenyan border, police dispersed his convoy with tear gas and live fire. Two days before the election, as he attempted to move from one rally to another in the capital Kampala, Besigye and police clashed about whether his favoured direct route would disrupt business too much. He was arrested again, and one bystander was killed in the resulting riots between police and his supporters.

These are the signals through which the president indicates to the electorate that he is more powerful than the state’s democratic institutions. Many of these acts are authorised by the Public Order Management Act (POMA), which gives police the power to assess all gatherings of more than three people. When Mbabazi decided to challenge the President for the ruling NRM’s presidential nomination, it was under this law that the police cancelled his meetings with party officials in Mbale, stating in an open letter that the party had already decided that Museveni would be its sole candidate, and that he therefore had no reason to mobilise a challenge. This was a cruel irony given that it was Mbabazi himself that pushed POMA through parliament as Prime Minister two years prior.

While these events grab the headlines, the real muscle of the state’s coercive apparatus is felt much closer to home. In rural areas, declaring support for opposition candidates can jeopardise one’s employment or business, and draw the menace of the elaborate security agencies that reach all the way to village level. As citizens rely on the grace of these organs to secure them against livelihood threats like land grabbing and to provide basic policing, their estrangement is more than a nuisance.

A new factor in this election is the deployment of so-called “crime preventers”. These are unpaid youths given several months training by police, officially as a reserve-cum-monitoring force. There are fears, however, that these could be an organ of further intimidation and repression. Grounding these fears, crime preventers are routinely clothed in yellow NRM shirts and deployed to manage crowds at ruling party rallies. It is not clear what role if any they will play on election day, but if intimidation is their main role then they may have already served their purpose.

State-party closeness

Across various agencies of government, it is difficult to distinguish the boundaries between party and state, a phenomenon most evident in the security organs. When police pulled down Mbabazi’s campaign posters in June due to the campaign season not having officially started, they left Museveni’s posters in place. Police spokesman Fred Enanga defended this selective treatment by claiming that ‘The president is the fountain of honour and he enjoys absolute immunity for whatever actions and enjoys structural advantages. You cannot just pull down his pictures under whatever circumstances.’

Civil servants are similarly engaged in the government’s campaign. Resident District Commissioners, who are barred from partisan politics, routinely show up at government rallies and make speeches lobbying for the incumbent. Likewise, laws designed to keep tribal leaders out of politics are routinely flouted by the Museveni campaign. These “traditional rulers” frequently appear at the President’s rallies despite constitutional bans on them doing so. Those who flirt with the opposition are afforded no such pardon. The same is the case for military figures, who are also legally banned from active politics. See here the alternate fates of Major General Henry Tuukunde and General David Sejusa: the former openly organises the President’s campaign (even landing the campaign helicopter at a rival’s rally); the latter was court marshalled after a streak of regime-critical statements a week before the election and remains in remand.

Yet the enduring paradox of Museveni’s Uganda is that voters often see the appeal of these Janus faces without objecting to their contradiction. As long as most people continue to fear a return of the pre-1986 turmoil more than these excesses, the regime will continue to mobilise massive majorities in the countryside. One Besigye voter told me of his neighbour’s reactions to his attempts to build opposition support in his village: ‘We are just sleeping… don’t cause us problems.’

To many here, the strong-man tactics such as those listed are only proof that Museveni is the sole leader strong enough to transcend the country’s fractious historical divisions. With memories of those divisions still surprisingly fresh, the general they know is better than the one that they don’t.

The author is a Uganda-based researcher whose name has been withheld to protect the author. This article was updated on 19 February.