Papua New Guinea: Students Shot, Country Damaged

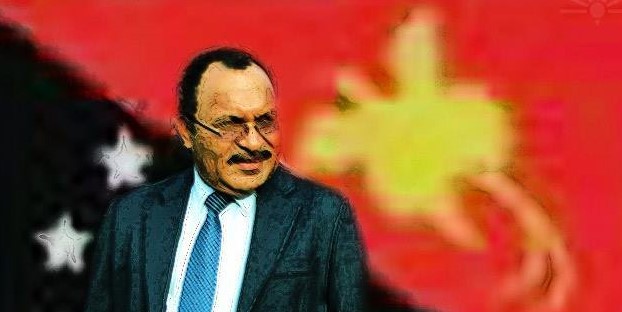

Last week’s Papua New Guinea police attack on students comes amid growing concern about political corruption under the government of Prime Minister Peter O’Neill. With the 2017 election in sight, the latest attack could prove damaging to the government as trust in its leadership falters.

On Wednesday 8 June, PNG police fired on a peaceful student demonstration at the University of PNG (UPNG); four students received bullet wounds, 20 were injured and hundreds tear-gassed. Thankfully there were no fatalities. PNG has again made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Even United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon expressed his concern, appealing for calm and respect for peaceful protest, freedom of assembly and a commitment to the rule of law. Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop, PNG’s founding prime minister Sir Michael Somare as well as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and Transparency International all made variations on those comments.

How did this happen?

As I flagged in January, public concern at political corruption has escalated under the government of Prime Minister Peter O’Neill. He has refused to be interviewed by the police over US$22 million payments to lawyer Paul Paraka, thus provoking a court-issued arrest warrant. And he is fighting an investigation over US$1.2 billion worth of loans borrowed without parliamentary approval. The state is in fiscal trouble. Foreign exchange reserves are short as income from liquefied natural gas has effectively been garnished to repay the loans. Budget cuts are severe. Health and education, for example, have been hit by cuts of around 35 per cent.

UPNG students have been boycotting classes for five weeks due to concerns about government corruption and PNG’s precarious economic position as well as a desire to preserve democracy and the rule of law. They have petitioned O’Neill demanding he step down (or at least step aside) while the charges are dealt with according to the law. The prime minister, who dominates the parliament, has stated that there is no case against him. But, as former chief justice Sir Arnold Amet points out, that is for the courts to decide.

The students and the prime minister appear to have angrily painted themselves into opposing corners. No third party mediator has emerged yet. Student concern and wider public distrust of O’Neill’s government has been fanned by vigorous analyses in PNG’s outspoken social media. The prime minister seems to be running scared.

In April the National Court lifted a ban on the police fraud squad investigating the Paraka case. Three arrests related to O’Neill’s case soon followed. The Attorney-General, Ano Pala, was charged with corruption; O’Neill’s lawyer, Tiffany Twivey, with perverting the course of justice; and senior judge Bernard Sakora charged with corruption in a case that failed this week, apparently over a procedural error. O’Neill’s Police Commissioner, Gari Baki, shut down the fraud squad office, despite a court order, saying he must vet all their work. He claimed this had nothing to do with the three high-profile arrests, but eventually was forced to reinstate the squad.

Mass meetings of students continued throughout the UPNG boycott, with the campus peaceful, but tensions rose when the university invited police onto the campus. In late May the UPNG Council cancelled the semester and ordered students to leave campus residences. With little to lose, teams went out on awareness campaigns in their home provinces, with some success. Sometimes they were blocked by police, who are ever fearful of unruly crowds. In early June the National Court ordered the university to stay open.

Then, on 8 June the small Opposition initiated a motion of no confidence against the O’Neill government. About 1,000 students, men and women—feeling safe and mistakenly believing they had a permit to demonstrate—tried to board buses to go to parliament. Blocked by police, they tried to march onto the main road. There they were blocked again by police with automatic rifles and tear gas. They refused to accept the arrest of their leader in a heated argument with police commanders.

PNG’s undisciplined and poorly trained police are often trigger-happy and their often ill-advised use of tear gas has helped create many a riot. Suddenly, some police fired what they claimed to be warning shots. They alleged this was in response to student violence, which the many witnesses deny. At least four bullets were fired. While police rapidly unleashed tear gas, they chased and beat the fleeing students. Locals there heard rumours of killings, some sheltered students and a police residence was attacked. Minor disturbances erupted in other volatile areas of the city and further afield.

The situation remains unresolved. That afternoon Prime Minister O’Neill made a statement to the House blaming students and outside political agitators. He set up a full inquiry—by the police—into the student protest. Critics have condemned the disproportionate police action and called for an independent inquiry, while the police commissioner blamed social media for spreading alarm. O’Neill then used his overwhelming majority to adjourn parliament until August. By August a vote of no confidence will no longer be possible, meaning that O’Neill has effectively removed a political safety valve.

Public hostility—not just to the police but also to the once-popular O’Neill government—is growing. History seems to be repeating itself. The Mekere Morauta government was badly damaged in June 2001 after three protestors were killed by police on campus during demonstrations against privatisation policies. The entire academic year ended, and many students lost their opportunity for higher education. It could happen again. UPNG students on Thursday said they would continue their protests, despite a new court injunction banning them from further campaigning.

The student protestors are all members of their clans back in their home provinces. Their campaigns will likely hurt current parliamentarians in the 2017 election. Whatever the outcome, hopefully all political actors in PNG can find a way out of this damaging conflict. If PNG is to succeed in doing so, it will be crucial to increase public trust without further damaging democracy and the rule of law.