Will Iran become the world's tenth nuclear weapons state?

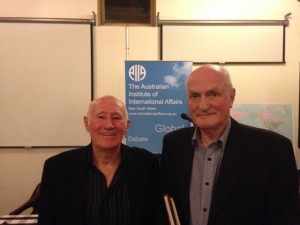

Richard Broinowski and Bob Howard

On Tuesday 29 September, fellow AIIA NSW councillor Dr Bob Howard and I discussed the nuclear deal between the G6 and Iran. Both of us have been following negotiations closely. Would the agreement work? I said there was no proof that Iran had a nuclear weapons program, but even if it did, the deal would set back its realisation by ten years or more. The deal had been concluded in Lausanne on 2 April. It required Iran to re-design, convert and reduce its nuclear facilities. More specifically, its enrichment plant at Fedow would close (leaving only the one at Natanz operating); its heavy water IR-40 reactor at Arak would continue to operate, but plutonium produced in it would have to be exported for IAEA safekeeping outside Iran; and Iran’s inventory of centrifuges producing enriched uranium 235 from uranium hexaflouride would be reduced from 19,000 to 6,104. Iran would not be able to enrich uranium 235 beyond 3.67 percent, and its existing stockpile of slightly enriched uranium would have to be reduced from 10,000 kilograms to 300 kilograms. Iran would continue to be able to operate its power reactor at Bushehr, provided the spent fuel went back to Russia for storage, and its various research reactors in Tehran and Isfahan would continue to be able to operate under strict IAEA safeguards. The IAEA additional protocol would apply to all Iran’s nuclear facilities. In exchange for all these concessions, all economic sanctions against Iran would be lifted, and the country would regain some of its stalled prosperity.

Bob observed that despite earlier mutterings to the contrary, Congress was likely to approve the deal without the need for presidential enforcement. Despite fulminations emanating from Jerusalem, there remained little taste for military action, and dawning realisation that sanctions were no longer likely to work. The deal was rigorous and intrusive, and would inhibit regional nuclear proliferation. If Iran was found to be in breach, sanctions would ‘snap back’. In the meantime, Iran, like Brazil and South Africa, would not have to eliminate its civil nuclear program. Any reconsideration in Tehran as to a nuclear weapons option would depend on the future geostrategic situation in the region. Some things would not easily change. Iran sees itself defender of the Shi’a world, Saudi Arabia the defender of the Sunni world. Enmity and suspicion between Iran and the United States was based on many grievances, both real and imagined, and relations with Washington were likely to remain guarded into the foreseeable future. Bob observed that this kind of treaty arrangement was messy and risky, but infinitely preferable to the alternative – a nuclear-armed Iran with several other countries, notably Saudi Arabia and Turkey, likely to follow hot on Tehran’s heels.

Report prepared by Richard Broinowski