Recentralisation of Power In Indonesia

As Indonesians go to the poll today some commentators have extensively criticised presidential candidate Prabowo Subianato, even comparing him to Indonesia’s long-standing dictator, Soeharto.

Comments made by Indonesia’s presidential candidate, Prabowo Subianto, to do with the semi-recentralisation of power into the hands of the executive have drawn criticism from commentators who have been quick to make comparisons between him and Indonesia’s long-standing dictator, Soeharto. One article, by Inside Indonesia’s Ed Aspinall compared him to 1930s European fascist dictators. Yet it is possible that some recentralisation of power within Indonesia’s central government could not be all that bad.

A Less Than Ideal Candidate

Prabowo Subianto may be seen as a less than ideal candidate. His sketchy human rights record during military campaigns in East Timor and West Papua, not to mention his dismissal as KONSTRAD army commander following abductions and instances of torture during the Reformasi period, are enough to leave some astonished that he is a presidential candidate. He is also part of the ‘old guard’ in Indonesia, a wealthy group of the elite that make up Indonesia’s oligarchy. Putting this aside, however, a more centralised Indonesian Government might have its merits given the current structure of the Indonesian political system.

The Problem of Power Decentralisation

Many commentators have noted the difficulty in pushing through political and social reforms in Indonesia, partly because of the rampant decentralisation of power from the central government. If the next president had increased powers to help push through reforms, some outcomes might be beneficial when considering the stasis of previous ruling coalitions.

Since the Reformasi, Indonesia’s national parliament, the DPR, has featured diffuse ruling coalitions. The next coalition in Indonesia would likely feature no less than five political parties, each with their own political agendas and vested interests. The highest scoring political party in the 2014 legislative elections, the Indonesian Democrat Party of Struggle (PDI-P), won roughly 19% of the votes, followed by Golkar with 14%, Geridra with 12%, Partai Demokrat with 11%, and various other percentages ranging between 5% – 9% for the following six highest scoring parties.

Indonesia’s Coalition Governments

In order to form a government and push through legislation deals are made, votes are bought and favours are promised to benefactors of political campaigns, however these measures are not enough to ensure loyalty within coalitions. This is something that Prabowo is almost certainly doing at the moment and, depending on your level of romanticism, something that Jokowi and his party are in the process of organising as well.

It is surprising that Indonesia’s political system has functioned as well as it has given the competing interests involved in successive coalition governments. Consensus does occur and every so often the stars align with some form of policy being the result. Whether that policy is for the benefit of Indonesia as a whole, it is sometimes hard to say.

Political Standstill

Keeping these competing interests in mind, it is hardly surprising that Indonesia’s outgoing presidential incumbent, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), has had to deal with opposition to reformative programmes. Important policies such as the reduction of Indonesia’s fuel subsidy were effectively hamstrung by the Indonesian parliament when they were deemed no longer in respective parties’ interests. Commentators have suggested that despite SBY’s tenureship being relatively sound, it will be remembered for an inability to get things done. Indonesians are critical of the inertia of their outgoing government and recent polls suggest that, despite anti-democratic rhetoric exhibited by Prabowo, many want a decisive government that is willing to implement change.

The next Indonesian president will have to address important issues of reform currently facing the government. Healthcare, anti-corruption, underdeveloped infrastructure and an overripe civil service are just some of the snags that experts have suggested are impeding development. Perhaps some degree of centralisation could help overcome these barriers. That is assuming, perhaps quite naively, that the next president is tough on corruption and willing to make the necessary changes in the right direction for future reforms.

Paving the Way for Reforms

A return to Soeharto-era authoritarianism would be a step backwards for Indonesia; the ideal is a diverse government that can reach consensus. But the likelihood of consensus within the current political situation might be low.

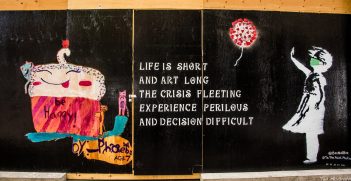

In the end it is the degree to which power is centralised in the president’s hands that matters the most. Although a return to Soeharto-era authoritarianism seems unlikely given the progress already made through decentralisation and the increased role of the free press in post-Reformasi Indonesia, Prabowo’s comments are still of some concern. The suggested rollback of the Indonesian constitution to its original 1945 form is especially worrisome as would allow the president to go beyond the current maximum of two terms in parliament. However, the role of the Fourth Estate in bringing leaders to account should not be underestimated, especially when taking into consideration Indonesia’s thriving and varied media/social media landscape: a key difference from that of the Soeharto era.

Andrew Catton is an intern at the Australian Institute of International Affairs National Office. He can be reached at intern2@internationalaffairs.org.au.