Migingo Island: Stern Test for Peacebuilding in East Africa

The tiny island of Migingo on Lake Victoria has been at the centre of a territorial dispute between Kenya and Uganda for many years. The competing claims over its sovereignty have threatened to ignite the continent’s “smallest war” but they have also led to a diverse range of peacebuilding measures.

Migingo is one of the many small Islands that dot Lake Victoria. Roughly the size of a football pitch, it covers an area of approximately 2,000 square meters. It is thought to be one of the most densely populated places on Earth, with some reports suggesting there are up to 500 people living on the tiny half-acre islet. If correct, this would equate to 250,000 per square kilometer. Geographically, it is often derogatorily referred to as a “tiny piece of rock.” However, despite the rather demeaning descriptions of this densely populated islet, it continues to receive much attention in both local and international media. A bitter dispute between Kenya and Uganda over its sovereign control has been running for many years. Both nations claim the island is within their territorial waters.

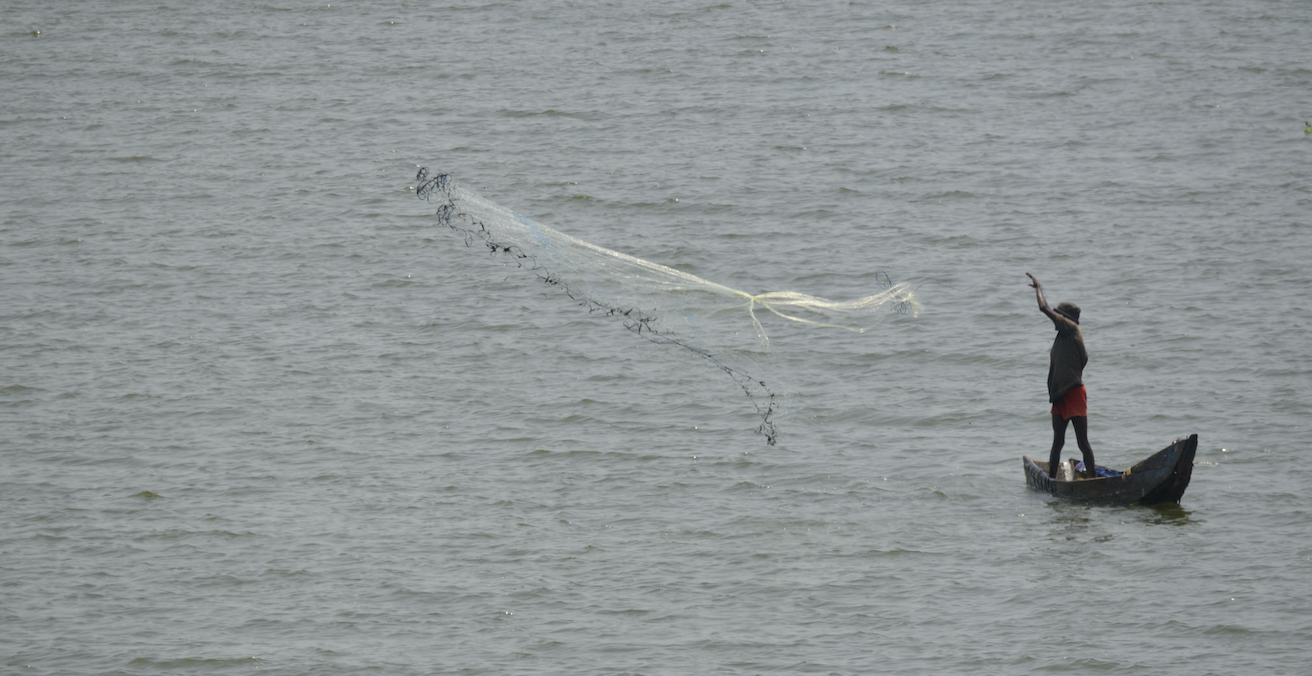

Kenya and Uganda’s territorial claims are largely motivated by their desire to control the lucrative fishing trade around the island. Over the years, fish stocks in Lake Victoria have become depleted through overfishing and environmental degradation. But in the deeper waters around Migingo Island, there are still plentiful stocks of fish such as Nile perch which command high prices in overseas markets.

Uganda has justified its claims to Migingo with archival colonial maps which it claims clearly show the island is theirs. Kenya, on the other hand, has argued its position on the basis of different sets of colonial maps and the claim that the island is 100 percent inhabited by members of a Kenyan community, the Luo. As claims and counterclaims are disputed, the island provides a stern test for East African peacebuilding.

Several efforts have been made to resolve the stalemate and to prevent it from escalating into a full-blown conflict between the two neighbours. In 2009, it was reported the two disputants had launched a US $2 million survey plan to determine the ownership of the island in order to help heal the festering diplomatic wounds. The preliminary reports from a month-long survey indicated Migingo actually belongs to Kenya, but no follow-up measures were taken by the regional confederation to intervene and end the dispute.

The most significant diplomatic move over Migingo was the withdrawal of Ugandan forces from the island in March 2009, an act that was largely interpreted as the fruits of successful reconciliatory engagements between the leadership of the two countries. However, the withdrawal did not last. It was not long before Ugandan forces returned to the island and reiterated their territorial claims. Later in 2014, a group of Kenyan fishermen in conjunction with the African Human Rights Bureau filed a petition against the Ugandan government at the International Criminal Court (ICC). It is believed the ICC was considered as a legal mechanism for dispute resolution because of its power to prosecute individuals charged with crimes against humanity, including the forcible transfer of populations. But the ICC soon lost interest in the matter and the initiative fell flat.

Further peacebuilding efforts followed when Kenya and Uganda struck a deal on Migingo in August 2016. According to this agreement, Ugandan security personnel would be allowed to cross over to Kenya for food and medical supplies and Kenyan fishermen would be able to sail freely in Ugandan waters. This deal was hailed by many as significant, fair and rational. Despite the earlier survey report indicating that Migingo is within Kenyan territorial waters, viable fishing is only possible within Ugandan waters. This is because the island and the Kenyan waters around it do not yield much fish, whereas the Ugandan waters do. This has led many analysts following the dispute to agree the dispute is simply “fishy” and not “rocky.” However, both sides failed to put measures in place aimed at enforcing and sustaining this peace deal.

In September 2013, an agreement for joint management of the island was signed by Nyatike Sub-County Commissioner Moses Ivuto and his Ugandan counterpart representing Namaingo District, John Wafula. The aim was to end the island’s security stalemate. Unfortunately, just like the previous dispute resolution efforts, this was also reneged on.

In 2016, Kenya and Uganda finally agreed to form a joint task force that would see police from the two nations patrol the disputed island and their common border in Lake Victoria. This move was largely seen as a bid to end hostilities and assuage diplomatic suspicions. However, it did not take long before Ugandan authorities forcefully removed the Kenyan national flag that had been hoisted on the island.

In addition to the diplomatic and legal mechanisms which have been deployed to mend relations between Kenya and Uganda over Migingo, other measures have also been proposed. The most novel of these is the suggestion fish could be farmed in cages in Lake Victoria. The idea is that by promoting alternative sources for fishing, this will help to draw the focus away from the disputed island.

Leaders amongst the Kenyan opposition have expressed their displeasure with the manner in which the matter has been handled by the Kenyan government. The leaders have accused the government of complacency and fence-sitting after reports emerged of disruption of voter registration on the island. Registration was being conducted by Kenyan electoral agency officials in preparation for the general election of 2017 when Ugandan forces confiscated equipment and ordered the exercise to stop. The opposition leaders have also condemned the beating up and arrest of Kenyan security forces and the closure of the only pre-school on the island by Ugandan forces in 2017.

In September 2018, tensions escalated again after Ugandan police stormed the island and lowered the Kenyan flag. This latest incident is being perceived by analysts as a breach of a peace agreement signed on 26 June 2018. A Kenyan resident on the island identified only as Mr Ochieng claimed that when the Kenyan police tried to raise the flag which had been pulled down, it was lowered a second time by Ugandan police who warned against trying to raise it again.

Up to now, both Kenya and Uganda still claim ownership of Migingo. Both the public and the relevant government institutions from Kenya and Uganda are currently awaiting the results and recommendations from inter-government commissions that have been appointed to find ways of resolving the dispute. Meanwhile, as fish stocks on the Kenyan waters continue to dwindle due to overfishing, invasive weeds like the water hyacinth, poverty and population pressure, the disagreement is likely to continue.

The dispute is largely viewed as a threat to regional peace and security as it raises pertinent issues about the international law regarding respect for and protection of territorial integrity. According to Article 2(4) of the Charter of the United Nations, which is reiterated in Article III paragraph 3 of the Charter of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), Uganda’s activities may be interpreted as acts of aggression. According to international law, such acts may be repulsed by Kenya through the use of force based on the principle of self-defense in Article 51 of the UN Charter.

For now, it remains to be seen whether diplomacy, international law, the co-management agreement, innovative fishing technologies or the peace agreement signed in 2018, will ultimately end the dispute between the two East African neighbours.

Enock Mac’Ouma is a research fellow at the Center of Media Peace and Democracy and a research assistant in charge of external linkages and collaborations at Rongo University, Kenya. He is a member of the International Association for Media and Communication Research, the European Communication Research and Education Association and the Public Relations Society of Kenya.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.