Meeting Saddam’s Men: Looking for Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction

The National President of the AIIA, Allan Gyngell, launched a new book, Meeting Saddam’s Men: Looking for Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction by Ashton Robinson, at the Australian National University on 25 October. This is an extract from his remarks.

Compared with the rich trove of memoirs from American practitioners, Australia has far too few accounts from our diplomats, members of the armed forces and intelligence officers about the practical processes of Australian engagement with the world.

Such accounts are not just interesting; they’re important. They can give the Australian public a much better understanding of the way our statecraft operates than the long wait for the archives to be opened for the professional historians.

Ashton Robinson’s new book has an additional value in helping us understand how the United States decision to invade Iraq in 2003 contributed to the dysfunction of the current international order.

As Ashton writes, “The Iraq war … altered the strategic geography [of the Middle East] more profoundly than any event since the creation of Israel, not least by altering the strategic balance in Iran’s favour. It also paved the way for the strategic rampage of the self-styled Islamic State of Iraqi and the Levant (ISIL) through the region after the fragmentation of Iraq and the collapse of the Arab Spring… President George W Bush’s launching of a major war in response to a non-existent WMD threat diminished much of the moral authority that the United States and the broader West had accumulated by the end of the Cold War.”

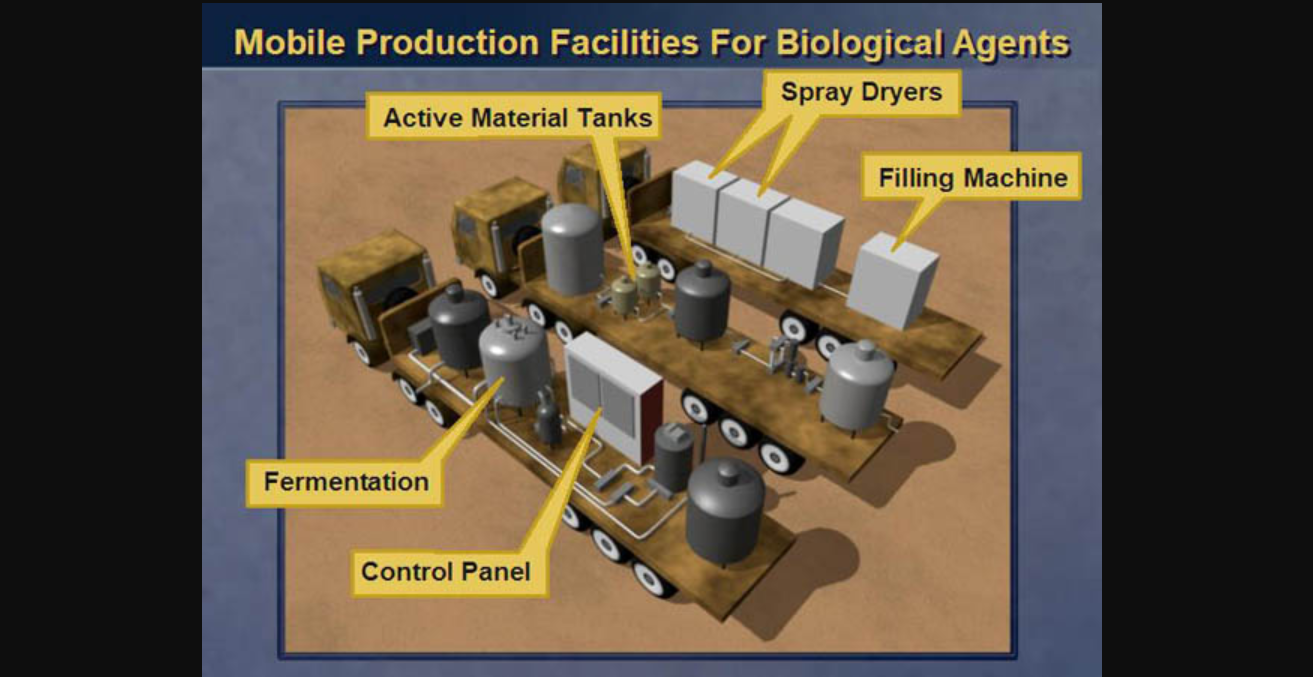

The heart of the book is the period in 2004 when Ashton was in Baghdad as a participant in the Iraq Survey Group (ISG), the trilateral body, involving the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, created hurriedly in 2003 to find and account for the weapons of mass destruction which were the ostensible cause of the war itself.

But he also gives us a comprehensive account of how Iraq had reached a point where its WMD programs were of such concern to the rest of the world, a persuasive description of how the ISG operated and reflections on the nature of contemporary warfare.

We get portraits of a number of admirable and honourable figures, notably including Charles Duelfer, the American official in charge of the ISG and the author of the report which summarised its findings. Those findings, as Ashton notes, ‘definitively put to rest the story of Iraqi WMD’.

But one of the admirable features of the book is the astute and humane way in which Ashton describes not just the allied figures trying to discover the truth, but the roles and approaches of Saddam’s Men, especially the four senior leaders of the Iraqi weapons program whom he interviewed in detention. These men, including Tariq Aziz, Taha Yasir Ramadan, and “Chemical Ali”, were all servants of an appalling regime and culpable in their own ways, but they nevertheless emerge from Ashton’s account as complete human beings.

Australians have averted our collective attention away from the origins and consequences of the Iraq war. In part that is because it was so clear from the start that Australia’s principal interest was in alliance management with the US. We haven’t, and won’t, see here any equivalent of the UK Chilcot Enquiry’s forensic examination of the decision to participate in the war.

That’s a pity because there is much to learn and our commitment was substantial. As Ashton notes, Australia’s six-year air campaign in Iraq and Syria concluding in 2017 probably exceeded anything the RAAF had undertaken since 1945, including the air campaign in the Vietnam war.

But in the absence of such a review, there are plenty of lessons for Australian policymakers to take from Ashton’s book.

First, investing in ideas pays off. Australia’s long involvement in the work of arms control and our technical knowledge of chemical weapons was instrumental to our capacity to contribute to the ISG. It was the reason we were nationally held in such high regard.

It’s a reminder that if Australia is to have influence on shaping international responses to contemporary international issues, ranging from climate change through nuclear weapons to cyber security, we need to ensure we have officials who can engage in the debate at the most detailed technical level.

Second, Ashton again makes the basic point, central to the Australian model of intelligence first put in place by Justice Robert Hope, that we always need to ensure that our intelligence process and our policy responses are separate and independent.

It was clear that the “faulty intelligence” the government had blamed for getting us into the war was not there. On the whole, as the review by Philip Flood showed, our intelligence agencies, especially DIO, did well. But if that independence of analysis is threatened, the consequences can be disastrous.

Third, and worryingly, we learn again from the chapter on the Oil for Food Program and the Australian Wheat Board how successful Saddam was in perverting the UN sanctions system and how willingly some Australian players participated in that, or averted their eyes from what was going on. Our own system is not immune from corruption and we must be vigilant against it.

This is an important work of history, analysis and reflection, imbued with deep moral purpose. Ashton Robinson has done all of us, including the next generation of Australia’s policy practitioners and intelligence analysts, a great service.

Allan Gyngell AO FAIIA is the national president of the Australian Institute of International Affairs and a former director-general of the Office of National Assessments.