A Global Nuclear Weapons Ban? Ready or Not, Here it Comes

Despite the apparent best efforts of Australia, the US and others, the second round of United Nations talks to negotiate a global nuclear weapons ban treaty is underway. With more than 130 countries participating, the proposed ban treaty may come into effect within the year.

On 15 June, 132 member states of the United Nations met in New York to begin the second round of talks to negotiate a treaty to ban nuclear weapons. Following a successful first round in March, the conference chair, Ambassador Elayne Whyte Gómez of Costa Rica, was confident that a text would be agreed to by the 7 July negotiation deadline. Her confidence does not appear to be misplaced. Issues in the three weeks of talks will be limited to the precise terms of a nuclear ban treaty and the size of the majority of countries voting for it in New York.

The draft text would prohibit states from using, testing, developing, producing, manufacturing, otherwise acquiring, possessing, stockpiling, stationing, transferring or receiving control over nuclear weapons. Moreover, the draft treaty bans states from assisting, encouraging or inducing anyone to engage in any of those activities.

Other parts of the draft deal with assistance to nuclear weapons survivors, the remediation of nuclear test sites, the establishment of a UN implementing organisation and conditions under which a nuclear weapons state may in the future forswear its weapons and join the treaty subject to verification and compliance requirements. The treaty would enter into force after being signed and ratified by 40 nations.

How has it come to this? The long-term explanation is fairly simple: the non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the existing non-proliferation treaty (the NPT) have waited for the five nuclear weapons states to meet their obligations to negotiate nuclear disarmament in good faith. After half a century, Austria, Brazil, Ireland, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa and another hundred or so countries have taken matters into their own hands. The goal of the ban treaty’s proponents is to create a legally binding regime that prohibits nuclear weapons and thereby begin a global political process that undermines the legitimacy of nuclear weapons possession and use in any form.

In the short term, one reason for the likely success of the negotiations is that the nine countries that possess nuclear weapons have boycotted the meeting. US diplomacy has been either inept, epitomised by Ambassador Nikki Haley’s squirm-inducing press conference outside the opening of the talks in March; absent, due to the vacancies on the upper floors of the US Department of State under Donald Trump; or quite simply left too late.

International reactions

Most US allies, sheltering under the nuclear umbrella, have stayed away, dealing themselves out of influence on the outcome. Australia, labelled a ‘weasel state‘ for its spoiler role in the lead-up to these negotiations, now finds itself regionally isolated, with all the ASEAN states and all South Pacific states not only participating in the New York talks, but taking active roles to promote a successful outcome.

Australia, following what is literally a US script, argues that the treaty will:

- slow down progress on nuclear disarmament;

- weaken existing nuclear treaty regimes;

- be useless because the nuclear weapons states will not be party to the treaty; and

- widen the divide between countries relying on nuclear deterrence and those that do not.

Some of these claims are disingenuous and specious, but some are correct. In fact, there has been little progress on disarmament for over a decade, and there is precious little chance of even business-as-usual arms control in the age of Trump and Putin. Contrary to Australian and US claims, however, the ban treaty seeks to build on and strengthen the NPT, and to create a new global norm stigmatising nuclear weapons possession.

True, Russia, Israel and others are not going to sign up for the treaty any time soon, but after the vigorous British debate on Trident II renewal last year, the UK looks very much like a plausible nuclear disarmament threshold state. Had Theresa May faced that decision not a year ago, but this week, caught between a promise of a state visit from US President Trump on the one hand and imminent Brexit negotiations on the other, who is to say the result would not have been different? Britain constitutes the weak link in the chain of nuclear weapons states around the world’s neck.

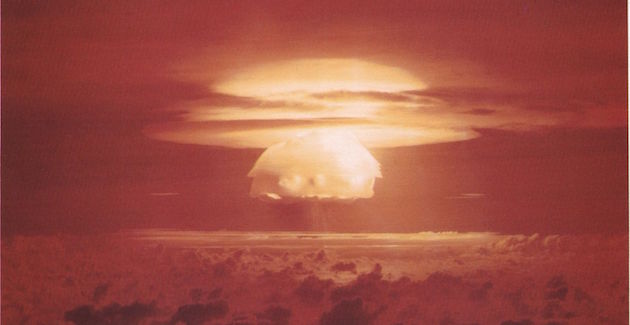

And it is certainly true that the treaty would deepen global divisions over nuclear weapons possession, as it should. Climate scientists have demonstrated that any use of even a fraction of the world’s 15,000-plus nuclear weapons in war will not only bring catastrophic and irremediable harm to the victims, but also precipitate a global climate disruption spanning decades, leading to massive famine and worldwide economic disaster. And that is before we begin to consider the arguments for nuclear abolition presented by Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un.

The treaty text is highly likely within three weeks, after which there will be a year or so of ratifications. This will be followed by a new campaign to take Australia off the list of countries whose defences rely on the nuclear annihilation of millions in neighbouring countries. And then, armed with a global legally binding prohibitionary regime, the long hard work of nuclear abolition can truly begin.

Richard Tanter is a professor at the University of Melbourne and chairs the Australian board of the International Campaign for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.