Can Advocacy Change the Views of Politicians About Aid?

The Australian Aid and Parliament Project (AA&PP), led by Save the Children, takes a “Presence-Based Approach” — which has both promise and limits — to influencing Australian Aid by seeking to build connections between aid beneficiaries and Australian parliamentarians.

The last decade has seen major changes in commitments to foreign aid from countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Given the reverberating economic impacts of the Global Financial Crisis since 2008, one might have expected to see uniform cuts to foreign aid in OECD countries. Yet changes to foreign aid commitments have not always been predictable. Many donor countries have reduced their aid commitments, with the Netherlands in particular abandoning its long-held target of 0.7 percent of Gross National Income (GNI). Meanwhile however, in the midst of austerity, the United Kingdom has increased to — and then legislatively mandated — a target of 0.7 percent of GNI. Within the last ten years, the Australian government, as this paper describes in more detail, has overseen both the largest scale-up of aid commitments in the country’s history, and its most severe cuts in history.

In all of these countries, non-government aid organisations, along with community groups, have sought to advocate for increases to foreign aid, or at the very least to prevent cuts. Yet aid advocates need to navigate an unusual form of politics in OECD countries. Unlike domestic policy areas in donor countries, such as welfare or education, the end beneficiaries of foreign aid spending have little voice in budget decision-making that affects them. Communities in recipient countries have no means of holding elite decision-makers in OECD countries to account. This article asks what the opportunities and challenges are for aid advocates working within the unusual policy realm of foreign aid: and in particular whether aid advocates can change the views of politicians about aid?

The Australian context — with its tumultuous increases and decreases of foreign aid commitments — is a rich one through which to examine aid policymaking and the role of aid advocacy groups. In particular, I draw on the example of the AA&PP, an aid advocacy initiative led by Save the Children. Within the highly centralised realm of decision-making around aid commitments, most aid advocacy has focussed on mobilising citizens of donor countries to pressure elected representatives to increase those commitments. Yet the constraint of such advocacy is that those citizens are not themselves impacted by aid, and the advocacy is based on OECD country citizens acting as a proxy for aid beneficiaries in other countries. The AA&PP takes a different approach by seeking to build direct connections between aid beneficiaries and Australian parliamentarians. Since 2015, the project has run almost forty exposure visits for Australian parliamentarians to grassroots aid projects in several aid beneficiary countries.

The History of Australian Aid

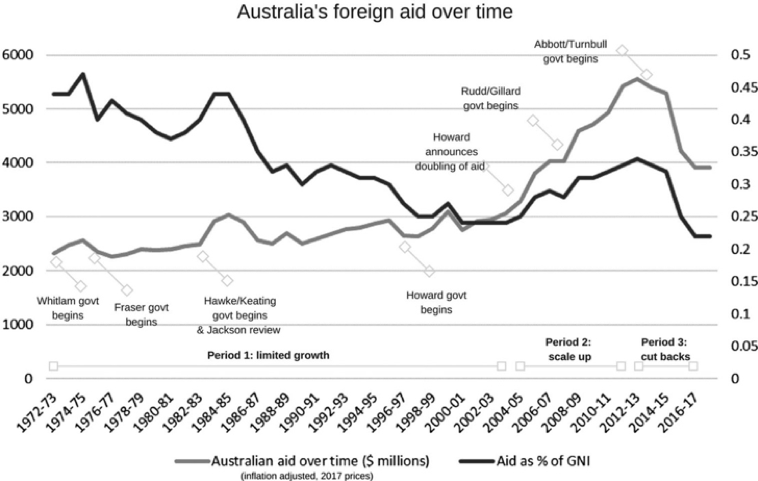

The history of Australia’s commitment to foreign aid in the last five decades can be divided into three distinct periods — 1972–2004, 2004–2013 and 2013 to the present. This history is instructive in highlighting the difficulties in building predictive models of aid commitments. The course of Australia’s aid commitments has not followed economic growth rates, nor has it been clearly guided by domestic political party ideology.

Figure 1. Data from Aid Tracker. Souce: @devpolicy via Wells’ article.

This history illuminates the crucial role of individual political agents such as Prime Ministers Howard, Rudd and Abbott, in profoundly shifting the trajectories of aid commitments. It is also important, however, to understand this history within the particular institutional context of aid commitments in the Australian government. In Australia, the budget process is a highly centralised one when compared with some OECD countries. The design of a new budget in Australia centres on a committee of Cabinet, the Expenditure Review Committee (ERC), which consists of the Prime Minister, Treasurer and the Minister for Finance, along with three or four other Ministers. Importantly though, the Minister for Foreign Affairs is not necessarily a member of the ERC. For example, in the Abbott/Turnbull government, Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop was not part of the ERC. Therefore despite reportedly making efforts to defend the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade budgets during the Abbott government, her influence on ERC decision-making was only indirect. These highly centralised institutions around aid commitments in Australia differ from other OECD countries in important ways. In the United States far more decision-making power around aid commitments resides in the Congress. Meanwhile, in the Cameron government in the United Kingdom aid spending was enshrined legislatively in 2015. These contrasting domestic institutions are crucial in defining the scope within which actors, such as Julie Bishop, could manoeuvre.

A Potential and Limits of a Presence-Based Approach to Influencing Australian Aid

Since 2015, with support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Save the Children Australia has been delivering the AA&PP. The project has undertaken learning visits to aid projects in PNG, Cambodia, Myanmar, Solomon Islands, Jordan and Lebanon involving almost forty Australian parliamentarians. The learning visits have involved a mix of party representatives: including Labor, Liberal, National, Greens and independent parliamentarians. A Labor MP contrasted this approach with other pro-aid advocacy strategies arguing that the AA&PP goes beyond “preaching to the converted.”

The aim of the project is to influence Australian political decision-makers toward an increase in aid commitments. This aim is then reflected in the selection of parliamentarians, with emphasis given to those who may enter party leadership positions in the future. Unlike formal diplomatic visits, the exposure visits of the AA&PP also aim to connect Australian parliamentarians with local level beneficiaries of aid projects. The focus of these visits is therefore primarily on humanitarian and development projects run by non-government organisations.

While the knowledge and attitudes of parliamentarians have shifted through the AA&PP exposure visits, this did not mean that these parliamentarians always felt that they could influence government aid commitments. A significant finding from this research was the perception from parliamentarians and ex-parliamentarians, even if they were pro-foreign aid, that they had few channels through which to exert their influence on decision-making about aid volumes. Participants in this study suggested that the centralised institutions of budget making in Australia presented significant limits to the scope of influence for parliamentarians. A former Labor minister said that the budget process and the role of the ERC were “not democratic” and significantly constrained the role of pro-aid advocates. Further, the lack of perceived societal support for aid in Australia more broadly was a significant issue for many parliamentarians involved in this research. Consistent with public opinion surveys, most participants reflected that aid had a low political salience amongst the public. Parliamentarians and ex-parliamentarians reported that aid was rarely discussed in the party room and was rarely an issue of concern for their own constituents.

Conclusion

Aid organisations and community groups in OECD countries need to navigate an unusual form of politics. This is particularly challenging in Australia where highly centralised institutions of budget making leave limited scope for the influence of parliamentarians, let alone non-government advocacy groups. The instinct for many pro-aid advocacy groups in OECD countries is to enlist the support of donor country citizens to act as a proxy for recipient country beneficiaries, and voice their support for increasing, or at least not slashing, aid commitments.

However, such efforts at mobilising public support have, in spite of some exceptional moments, generated wide but shallow public support for aid. Education of donor country citizens about the role of foreign aid — and their mobilisation in support of foreign aid — undoubtedly has a place in influencing aid commitments. Yet pro-aid advocacy resources are finite and need to be deployed by aid agencies to most strategically navigate the unusual domestic politics of foreign aid. The AA&PP provides an alternate model for addressing the challenging politics of aid commitments and the dilution of budgetary accountability. This study reveals that fostering direct connections between elected officials and local level aid beneficiaries, rather than just a proxy role of concerned citizens, can shift the attitudes of parliamentarians toward aid commitments. It is not just new ideas but new exposure to aid beneficiaries that can shift attitudes to foreign aid. In this sense, facilitating exposure visits for elected officials may be a valuable component of future aid advocacy spending in OECD countries.

In countries like Australia however, with highly centralised budget making systems, galvanising the support of parliamentarians may be insufficient for increasing, or even protecting, aid commitments. One significant finding from this study is that backbench parliamentarians, both in government and opposition, often feel they have little opportunity to influence the budget processes around foreign aid commitments. While parliamentarians can shift their attitudes when confronted with new ideas and experiences, the rules or institutions of foreign aid budget making — which are highly constraining in the Australian context — bring sobering limits to parliamentarian influence. Of course, if parliamentarians targeted through projects such as the AA&PP fill senior positions in political parties in the future — for example as part of the ERC — then this brings some potential for building support for foreign aid commitments. Finally, this study also reveals significant tensions between aid advocates in Australia about how aid policy changes happen, and whether or not to politicise aid as a policy issue.

Dr Tamas Wells is a research fellow in the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Melbourne. His research focuses on aid and politics in Southeast Asia and Australia. He worked for aid organisations in Myanmar from 2006 to 2012.

This article is an extract from Wells’ article in Volume 73, Issue 3 of the Australian Journal of International Affairs titled ”Can advocacy change the views of politicians about aid? The potential and limits of a presence-based approach.“ It is republished with permission.