Irish Peace Process a Borderline Brexit Issue

A hard Brexit will harm the Irish peace process, restoring the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The Democratic Unionist Party’s inclusion in a Conservative coalition government, however, increases the likelihood of a soft Brexit.

On Good Friday 1998, the governments of Britain and the Republic of Ireland came to an historic agreement over Northern Ireland. This was preceded by the 1994 IRA ceasefire and Sinn Fein taking the path to become a ‘normal’ political party. The EU was also a crucial innovator in bringing economic programs between the actors in conflict to a purely political settlement. The key was having ‘social inclusion’ as part of an economic program that would then be carried over to any political settlement. In particular, it brought the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Fein together; initially these two parties cooperated at the local district level over the EU provision of funds. Since the 1990s, these have also included funds to help economic development at the border between Northern Ireland and the republic.

The EU and the peace process

The peace process occurred because of a confluence of external factors involving economic transformation and the end of the Cold War. Economic unity saw the rise of an all-Ireland economy operating domestically and internationally. But the EU offered the institutional architecture through which Northern Ireland could advance. The EU established the basis of cultural, rather than sovereign, nationalism for both parties. Sovereignty over Northern Ireland would be left to the British government, but a referendum on a united Ireland may be held subject to the wish expressed by a majority. Meanwhile, the European Union provided funding mechanisms to reinforce local and regional cultural identity.

The EU’s process of transition provided a model that was applied in Northern Ireland. The European Economic Community preceded the European Union, with the goal of developing a European form of state. Northern Ireland moved from being an economic community to its own form of political union. This involved provincial representation with Britain as ultimate sovereign, the Republic of Ireland as potential sovereign, and the EU as a regional entity. This was the first step in producing European unionists content with Northern Ireland’s evolving role, rather than Ulster unionists or those who seek unity within Ireland. This was the model that the British government, the government of the Republic of the Ireland, Sinn Fein and eventually the DUP came to accept.

Brexit and the peace process

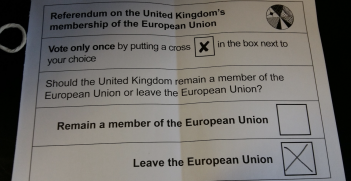

Then came the crisis of the Conservative Party under David Cameron and the decision to hold the referendum on Brexit, which was made with little thought about the problems of Northern Ireland. The peace process had relied a great deal on the European Union: the EU flooded Northern Ireland institutions and industry with cash in exchange for cooperation between contending sectarian interests; it helped establish the agreement of 1998, which was imperfect but nonetheless helped stop sectarian fighting. Class politics was beginning to overtake sectarian politics with the election of two left-wing politicians to the Northern Ireland Assembly. These advances were made after the elimination of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Now, this border between a future non-EU country and an EU country has been revived. In short, Northern Ireland existed perfectly well in the EU; now it faces the old problem of surviving within the UK.

Sinn Fein was on a slow path to unity through Brussels, but now it is stuck with London. This may open it further to ‘spoilers’ from right-wing Republicans. In anticipation that the struggle over sovereignty will return to the forefront, Sinn Fein must now campaign for a united Ireland. Sinn Fein cannot hope to win a border referendum, but in the 2017 elections it won all the border counties and can expect good results in these constituencies. Finally, it is an open question whether Sinn Fein will maintain its faith in the DUP as a negotiating partner within Northern Ireland, now that the DUP will play a crucial role in British government.

The UK election

Following the UK’s recent general election, the Conservative Party will need the votes of the DUP to stay in power. First, let me state a few facts about the DUP to undo some misinformation in traditional media and social media:

- The DUP has ruled Northern Ireland with Sinn Fein for 10 years. DUP founder, the Reverend Ian Paisley, and Sinn Fein’s Martin McGuinness got on extremely well.

- The DUP does not wish to see its policy on abortion go beyond Northern Ireland. Its policy on abortion is mirrored by the mainly Catholic Social Democratic and Labour Party.

- The DUP may reflect the bigotry of the Protestant population but with few exceptions does not engage in paramilitary activity.

- The DUP is a divided party. The DUP has become the hegemonic party in Unionist circles and, crudely put, the divide now is between rational economic versus protestant fundamentalist members.

- In that regard, the DUP has been caught in a series of corruption scandals. This is a good thing. They can get caught up in financial matters rather than religious fundamentalism.

In terms of the negotiations on Brexit, the DUP favours a soft Brexit with no interruptions to cross-border trade (the Republic of Ireland is Northern Ireland’s biggest trading partner). It also demands no checking of passengers flying from Northern Ireland to Britain. The latter will cause headaches for the Conservatives because of immigration concerns; particularly, EU citizens are entitled to work in the Republic of Ireland and they can walk across the border and then travel to Britain. It is likely that resolving these trade and people movement issues will hold up talks between the Conservatives and the EU. In turn, this will expose the Conservative Party to its key division between a soft and hard Brexit.

This government coalition is very bad for the Irish peace process. James Brokenshire’s reappointment as Northern Ireland secretary is owed to the DUP. Although he says his first priority is to get the Northern Ireland parties to form a devolved government, his first priority really is to now keep the DUP-Conservative coalition in power. Sinn Fein has already called for an independent negotiator rather than the compromised secretary of state. However, Sinn Fein is also backed into a corner, where all it can do is campaign for a united Ireland. It knows that this will fail, but it will be strengthened by votes in the border areas. In addition, it is likely there will be an increased atmosphere of tension around the marching season of the Protestant Orangemen in July and August.

Although harmful for the peace process, the DUP’s involvement is potentially a good thing for Brexit. The absence of a hard border with the Republic of Ireland and the implementation of a soft Brexit may well see the Conservative Party’s hard-right policy undermined. That Northern Ireland has finally come onto the agenda of the British government may be Britain’s just desserts. However, it is a pity that the British government did not consult with all the parties in Northern Ireland before embarking on its referendum on Brexit in the first place.

Dr Diarmuid Maguire is a senior lecturer at the University of Sydney Department of Government and International Relations.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.