Zimbabwe is Increasingly Looking East

Zimbabwe’s contemporary foreign policy has been coloured by anti-imperialist proclamations that the country will never be a colony again. These proclamations have been largely directed at the West due to tensions over the ‘land question’. Sour relations between Zimbabwe and the West have caused the country to look east towards China. But has Zimbabwe substituted one form of imperialism for another?

Foreign policy since independence

Since Zimbabwe achieved independence in 1980, the country has prioritised safeguarding its sovereignty. Zimbabwe has deployed defence forces on a number of occasions to achieve this goal. It deployed troops to protect the Beira Corridor in Mozambique and to counteract South African destabilisation initiatives in 1980. In 1998, Zimbabwe intervened in the Democratic Republic of Congo to safeguard geopolitical and economic interests in the spirit of Pan-Africanism—much to the chagrin of the West. However, while Zimbabwe has taken active steps to safeguard its sovereignty and pursue both its geopolitical and economic interests, in the 1990s it bowed to Western pressure and implemented structural adjustment programs at the behest of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Zimbabwe has also historically been an active participant in multilateral fora and a supporter of Pan-Africanism, good international citizenship, and the peaceful resolution of conflicts. African countries’ participation in peacekeeping operations is often overlooked, however, Zimbabwe has participated in several UN peacekeeping operations. These include those in Angola, Somalia, Uganda and Rwanda in the 1990s; and during the 1989-1991 mediation efforts in Mozambique and Angola. Additionally, Zimbabwe participated in UN police contingents in Bosnia, East Timor, Somalia, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Darfur in Sudan, as well as in bilateral and multilateral training of Southern African Development Community defence forces.

Zimbabwe also pursued relations with the then ‘Eastern Bloc’—China, Cuba, North Korea, Russia—in the 1980s, partly due to their support during the armed liberation struggle and to offset its historical dependence on the West. In the 1980s, Zimbabwe subsequently had an overtly socialist outlook, one driven by the need to redistribute wealth in a country where a white minority enjoyed much higher standards of living than the black majority, by virtue of holding most of the arable land. The Fast Track Land Reform Program, indigenisation, and black economic empowerment policies are, arguably, a continuation of this outlook. Despite the mismanagement of the land redistribution process, these policies are part of a broader commitment to egalitarianism, a commitment that the West has consistently undermined, including through the neoliberal IMF-led structural adjustment programs of the 1990s, and the IMF staff-monitored program reforms currently underway.

Foreign policy in the present

Arguably, multilateral fora such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the IMF, and the World Bank, have been part of a broader strategy to gain access to developing countries’ economies and resources in the post-independence period. The structural adjustment reforms that Zimbabwe and other African countries underwent have undermined intra-African trade, which currently stands at less than 12 per cent. Instead, most African trade is with countries of the OECD. Disputes in the WTO have often centred on African countries gaining access to OECD markets.

The West’s engagement with Africa has, therefore, been coloured by a need to maintain Africa’s historical dependency on the world’s traditional powers. And whilst China being driven by its own geopolitical and economic concerns is not in question, it increasingly presents a more desirable trade and investment partner. It is, of course true, that the Beijing Consensus upholds several ingredients of the Washington recipe.

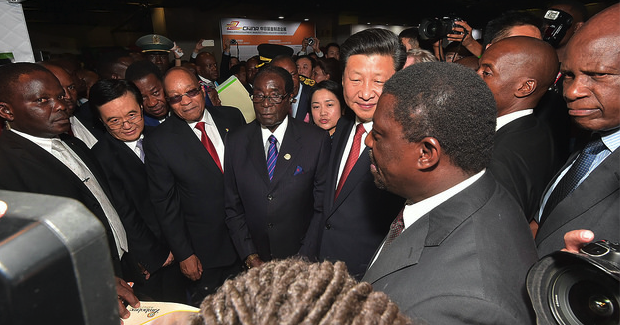

It can now be said that the West’s influence on Zimbabwe is in decline and Chinese soft power is leading the way. Whatever the content of the Beijing Consensus, China will soon be Africa’s preferred diplomatic and national development partner, with 63 per cent of Africans saying China’s influence has been positive. The Chinese show greater willingness to share their technology while the West, including Australia, seems afraid of African self-sufficiency. China has now become the country’s largest trading partner and Zimbabwe has even recently adopted the Chinese yuan as its primary international currency.

However, Zimbabwe’s trade relations are not limited to China, but spread throughout the Asia-Pacific and, indeed, Eastern Europe. Zimbabwe is attempting to disperse its economic dependence onto a range other countries. The implementation of the IMF-designed structural adjustment reforms to normalise relations with the West are also a part of these efforts.

Zimbabwe’s leaders also need to work with other African leaders through the African Union to develop a coherent regional foreign policy and approach to securing investment, coordinating infrastructure and other development initiatives at the sub-regional level. Less emphasis on sovereignty, and effective use of multilateralism with an eye to regional trade, integration, and development should be the focus. The people of Zimbabwe and the broader southern African region, must be the principal beneficiaries of any foreign policy approach.

Tinashe Jakwa is a master of international relations student at the University of Western Australia.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Licence and may be republished with attribution.